UK techno isn’t a genre as such, but it remains a criminally overlooked part of electronic music history.

The period from 1992 to 1996 was particularly strong, as myriad little-known producers released exceptional pieces of work, cross-pollinating a variety of styles and precipitating a whole slew of new genres.

British musicians have a knack of taking an existing sound and doing all sorts of peculiar, eccentric things to it. Consider how Soft Machine approached rock music in the 1960s, unwittingly birthing the prog behemoth and making it unfashionable. A similar fate arguably befell the simplistic early sounds of US house and techno. By 1993 early breakbeat had birthed hardcore, and drum ‘n’ bass was well on its way to becoming a totally separate strain, while under the umbrella of Warp records, a number of prodigiously talented artists – Aphex Twin and Autechre among them – were emerging with something that was still techno, but beginning to sound very different indeed.

The age of mass raves was now virtually at an end, with only the (now legendary) Tribal Gathering events left, along with the embryonic stages of the Big Chill. Club nights such as Lost, Sabresonic, Final Frontier, Atomic Jam, The Orbit, Voodoo and House of God sprang up to fill the void. The blossoming of Warp’s progeny was complemented by a host of similarly impressive homegrown production projects such as B12, LA Synthesis and The Black Dog. The sound of Americans Robert Hood, Jeff Mills and Dan Bell, invited by Steve Bicknell to play at Lost, set in motion a “minimal” trend that would see the flowering of labels such as Ifach and the aggressive thunder of The Advent and Bandulu, not to mention the more industrial approach of Birmingham’s Downwards.

Meanwhile, Detroit’s second wave would influence the likes of Kirk De Giorgio, Ian O’Brien and Steve Pickton, and, in Brighton and Edinburgh, slightly isolated more talents such as Neil Landstrumm and Cristian Vogel would begin to cultivate their own ideas of what techno was and could be. Kiss FM in London even had its own radio show dedicated to the genre, hosted by Colin Dale.

Yet by 1996 the music itself and attitudes within clubs were changing, and not altogether for the best. Whilst undoubtedly the DJ of the ‘90s, Jeff Mills’ three-deck approach – which had laid to waste many a dancefloor during an epochal period of ’94-’97 – had begun to influence a new army of producers and DJs who were interested in the monolithic dynamic of “chunky” techno, a sound encapsulated and influenced not just by Mills’ own Axis productions but also a slew of compressed Drum Code records coming from Sweden. Melody and emotion were sacrificed to this relentless minimalism, and from a DJ’s perspective, it was soon more about how many records you were mixing rather than whether the tracks themselves were any good.

An era of looped techno had begun, and in my opinion it damaged some areas of the scene permanently; numbers in clubs dwindled rapidly, crowds only interested if the big US DJs such as Mills, Hawtin or Derrick May happened to be playing. Nonetheless, the contrast between the quality of British techno records released now and in 1995 is utterly startling, with only a handful of producers still pushing the genre forward. Like those prog rockers in the late ‘60s, many musicians in the field realised the genre’s limitations, and sought to experiment elsewhere.

So what’s the point of this article? Artists such as Aphex Twin, Dave Clarke, Autechre and Underworld have all sustained considerable artistic and commercial success over the past decade and a half, and none of those acts appear on this list. They’ve already received the exposure they deserve elsewhere. The 20 records I have chosen show that a goldmine of talent and ideas exists beyond the well-documented big guns, shifting the focus of techno away from its American roots.

There are many facets of UK techno that aren’t represented in this list, such as the burgeoning free party scene embodied by the anarchic Spiral Tribe, whose influence on Dutch labels such as Bunker is not to be underestimated, or the UK tech-house scene that emerged from South London. I have also steadfastly avoided mentioning the Gescom/Skam/Warp influence because to me it’s almost a separate genre that grew out of the period. This is of course a personal view, but I’ve taken care to include records and labels whose influence can really be felt in contemporary techno.

01. Clark

Lofthouse EP

(Planet E, 1995)

Mark Bell was in LFO, who lay a strong claim to being one of the greatest ever techno acts, and he also made this double 12”, released on Carl Craig’s label, which is arguably the finest techno record ever made. Although the influence of Detroit is clear, it’s the sheer range of textures and emotions spread over the seven tracks that make this release utterly essential. No techno DJ should be without it.

02. Luke Slater’s 7th Plain

The 4 Cornered Room

(General Productions, 1994)

Like Mark Bell, Luke Slater released enough fine music between 1992 and 1996 to warrant a ’20 best’ of his own. Slater pseudonyms such as Clementine, Planetary Assault Systems, Morganistic and the more self-consciously cerebral 7th Plain were responsible for some of the most fulfilling techno of the period, ranging from darkly intense albums like Fluids Amniotic to this, one of the genre’s true classics. Tracks like ‘Lost’ sum up what was great about UK techno at this time, in my opinion genuinely rivalling the likes of Derrick May and Carl Craig. Slater has never matched this run of creativity since, opting for a more electro-orientated and synth-pop approach during the early part of this decade, and latterly returning to his Planetary Assault Systems guise for an album on Ostgut Ton.

03. Reload

A Collection of Short Stories

(Infonet, 1993)

It’s difficult to talk about electronic music of this period without mentioning Mark Pritchard and Tom Middleton, who are rightly acclaimed for a number of outstanding albums under pseudonyms such as Global Communications and, to George Lucas’s chagrin, The Jedi Knights. This, however, remains their magnum opus. Originally a Pritchard solo project, Middleton became more closely involved during its composition; it remains one of the best of its type.

Veering from the bucolic ‘Ehn’ and ‘Le Soleil et Mer’ to what verges on downtempo industrial and the post-rave madness of ‘Mosh’, aided by an array of sci-fi cinema samples, this a sprawling, almost decadent record. It is flawed, but you’d be hard-pressed to find an electronic music album as downright ambitious.

04. In Sync

‘Storm’

(Irdial, 1992)

A major character in the evolution of UK techno, Lee Purkis set up the legendary Fat Cat, a record store that would dominate the hearts and minds of many in London during the ‘90s. This formidable single is almost impossible to find now on vinyl, but it’s worth investigating Irdial Discs, which remains one of the most outstanding imprints to come from Britain in the last 30 years.

All manner of fantastic oddities, both electronic and experimental, have emerged from the imprint, and due to their free music philosophy, virtually all of it is free to download from their site. It’s also worth checking the In-sync vs Mysteron album Android Architect on 10th Planet.

05. Baby Ford & Eon

‘Monolense’

(Ifach, 1994)

Ian Loveday, who tragically passed away just before this article was written, made some stunning records under the monikers of Eon and Tan-Ru, but it was this collaboration with Peter Ford that bore the stunning track ‘Dead Eye’, one of the best original minimal techno tracks around.

Ford’s Ifach label is up there with Plus 8, Profan, Sahko and M-Plant as one of the true leading lights of what was then very much an embryonic scene, and he has maintained his position as one of dance music’s stalwarts, still producing 20 years down the line.

06. Holy Ghost Inc.

‘Mad Monks on Zinx’

(Holy Ghost Inc, 1991)

The duo of Gary Griffith and Leon Thomson are perhaps better known for their crushing assaults with Tresor towards the end of the ‘90s, but this is their best effort – a haunting breakbeat record that goes against much of the then fledgling hardcore scene in 1991 and edges into melancholic trance territory. Take no notice of the Sabres of Paradise mix though; it has nothing on the original.

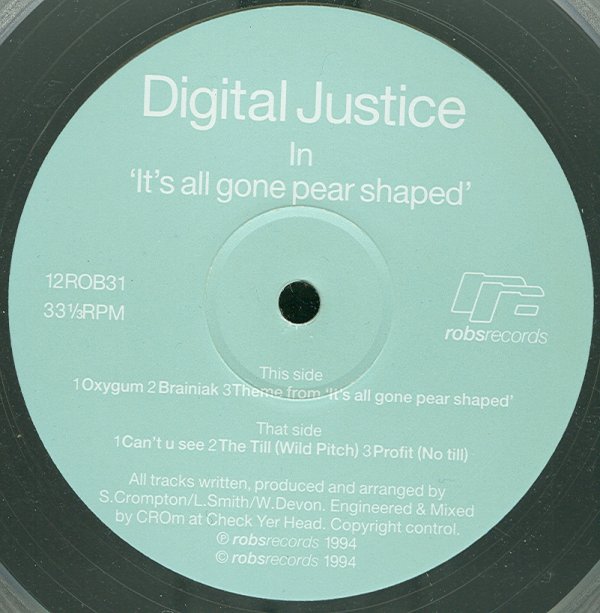

07. Digital Justice

It’s All Gone Pear-Shaped EP

(Rob’s Records, 1994)

Only one record was ever released by this group, but it remains one of the key moments in UK techno, six tracks that take in elements of house, breakbeat and the sort of trancey acid techno made famous by German labels like Harthouse. Every track on this relentlessly upbeat 45-minute EP is superb.

08. Bandulu

‘Presence’

(Infonet, 1994)

There are plenty of records in a similar mould from this period, and it could be argued that The Advent, who missed out on this list by the slimmest of margins, based their entire sound around this template, namely that of the pitched-up, incendiary rave bomb designed to be played in a strobe-lit, otherwise pitch-black room. It’s dark, atmospheric and mindless, and for me brings back strong memories of climbing the walls at Lost. Former member Jamie Bissmire is now part of the production and DJ duo Space DJz.

09. Stasis

Circuit Funk EP

(Peacefrog, 1993)

Like Warp, it’s a label that has seen better days in terms of its electronic music output, but at its zenith Peacefrog was releasing amazing records every month for around four years. Steve Pickton is a classic example of the hermetic techno producer, emerging at night to man the decks in the back room at Lost, and chucking out records like this glorious Detroit-inflected EP by day.

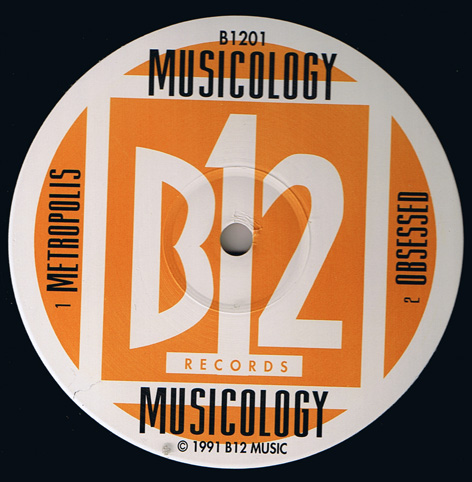

10. Musicology

Musicology EP

(B12, 1991)

Although they’d achieve greater fame as B12 on Warp, Michael Golding and Steve Rutter began life with this stunning 12” from 1991. I’ve personally never really seen what the fuss was with their later incarnation, and prefer this much sharper period of their history. The track ‘Telefon 529’, indicative of what was to come, made it onto Warp’s now-legendary Artificial Intelligence compilation series.

11. Ian O’Brien

Desert Scores

(Ferox, 1996)

O’Brien’s jazz-fusion influence came to the fore for this, his debut album on Russ Gabriel’s label. It’s a quirky affair, lacing his obvious love of Detroit (see ‘Mad Mike Disease’) with the sort of free-roaming approach to techno that one might associate with Carl Craig, most notably on the pastoral-sounding ‘Eurydice’. Gabriel and Kirk De Giorgio just missed out on this list, but they made a definitive impact with their own productions, most notably the latter with his Reflections album under the As One moniker.

12. Surgeon

Force + Form

(Tresor, 1999)

The ever-present 125-130 bpm thud at Berghain can be largely attributed to Tony ‘Surgeon’ Child’s early output, so influential are tracks such as ‘Atol’ and ‘Magneze’ which appeared in 1995 on Karl O’Connor’s Downwards imprint.

Child’s early material had an enormous kinetic energy about it, yet also sounded brittle, ready to snap. Force + Form moved away from this, inspired greatly by the avant-garde mysticism of Coil, a band that Child identifies as an essential part of his musical heritage. It’s a sprawling, experimental LP that owes a debt not just to Coil but also Throbbing Gristle and Liaisons Dangereuses, and to my mind it marks Surgeon as the premier exponent of techno over the last decade.

13. Cristian Vogel

We Equate Machines With Funkiness EP

(Mosquito, 1994)

Chilean-born Vogel set up shop in Brighton in the mid-90s and immediately went to work harnessing a wholly different techno aesthetic to the norm, one allied to the free party scene rather than the more linear approach being applied elsewhere in bigger clubs. His first release on his own Mosquito label has arguably not been bettered, being a savage, jacking attack of ideas and fantastic production crammed into just three tracks.

A progenitor of what became unfortunately known as “wonky techno”, Vogel remains a considerable talent. Now seen crooning like a soul star, early collaborator Jamie Lidell’s finest moment is arguably his ‘Freely Funkin’ release on the same label.

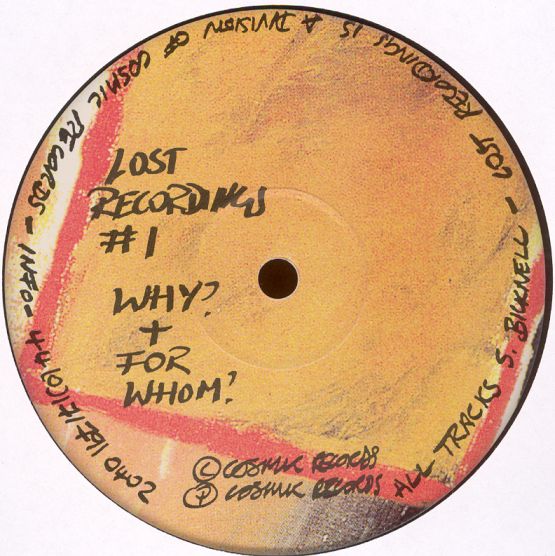

14. Steve Bicknell

‘Why? And For Whom?’

(Lost Recordings, 1996)

Architect of the legendary Lost nights, Bicknell remains criminally underrated as a producer, having released a number of diverse and somewhat obtuse recordings on his own Cosmic imprint since its formation in the mid-90s. Although it could be described as “tribal” in nature, the clattering, decidedly nocturnal musical vision of Bicknell steers well clear of the stereotypes that this description usually brings to mind, and is an excellent summary of the direction Lost and the less well known Burundi night was going in during the late ‘90s.

15. G-Man

‘Quo Vadis’

(Swim~, 1995)

The other half of LFO, Gez Varley, for me never quite hit the golden heights of his partner Mark Bell, but this simplistic minimal jacker, originally written in 1994 and released on an obscure label set up by Colin Newman of post-punk legends Wire, remains an utter classic.

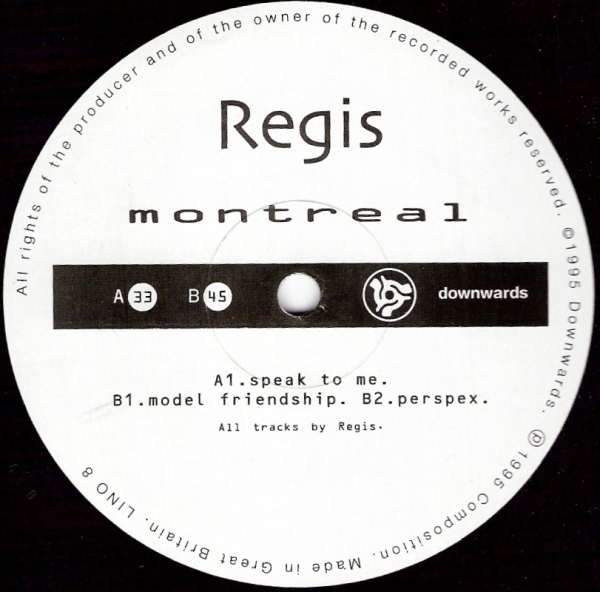

16. Regis

Montreal EP

(Downwards, 1995)

Karl O’Connor’s singular vision with Downwards crystallised what became known as the “Birmingham” sound, helped no doubt by long-time collaborator Anthony Child, aka Surgeon. It’s one of the first records to really take on board the growing influence of Jeff Mills, but retains a strong, no-nonsense identity of its own.

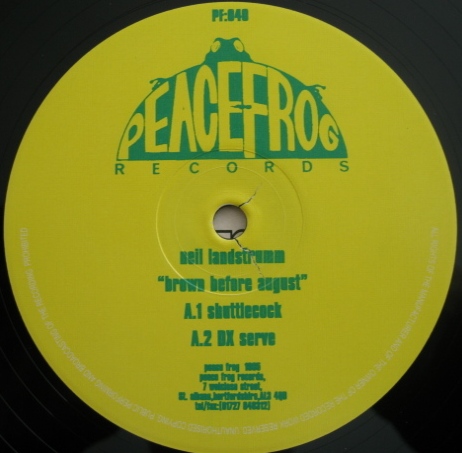

17. Neil Landstrumm

Brown By August

(Peacefrog, 1995)

Taking its influence from the brutalism of Chicago labels such as Dance Mania and Relief, Landstrumm’s first album was Edinburgh’s answer to Gemini and Robert Armani: a set of nine straight-up, gritty, distorted boxjams. It’s essential.

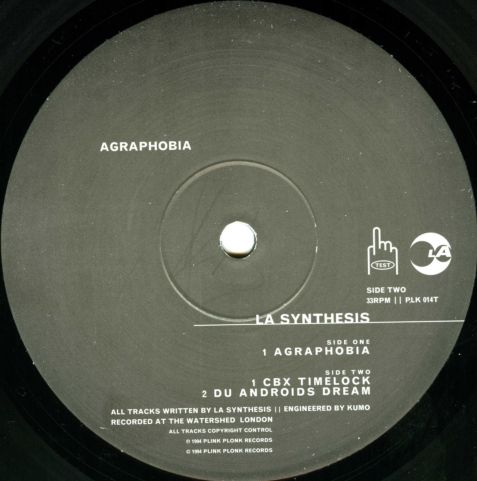

18. LA Synthesis

‘Agraphobia‘

(Plink Plonk, 1994)

Another in a long line of UK techno production duos, Carl Grant and Tony Gallagher never fulfilled their potential but they crafted one true gem in the form of this nine-minute, Model 500-influenced trance epic on Mr C’s now defunct Plink Plonk label. It’s an interesting remnant of an embryonic ambient/trance scene that would soon splinter off in another direction altogether.

19. Santos Rodriguez

Road To Rio EP

(Cosmic, 1999)

Released on Steve Bicknell’s label, this is one of the few records from the end of the decade to really make an impression. Maverick producer Arthur Smith operated out of a studio above Big Apple Records in Croydon, also releasing under the alias Grain on FatCat. There are slivers of the dubstep sound that he would play a large role in facilitating later on, helping launch the careers of Hatcha, Benga et al.

20. Andrew McLauchlan

‘Love Story’

(Bush, 2000)

Part of a nascent “Ealing techno” scene that came about in West London towards the end of the decade, populated by such producers as Oliver Ho and Max Duley, this Latin-flavoured techno track exemplified the direction that so many fans DJs, producers and clubbers had moved in in the wake of Jeff Mills’ Purposemaker sound.