Words: Kiran Sande

It’s June, 1999, or thereabouts. I’m sixteen years of age. I’m in a nightclub for the first, perhaps second time in my life. The nightclub is called Spiders, and it’s located on the edge of an industrial estate in Hull. The air as my friends and I queue up outside is foul with burnt cocoa fumes wafting from a neighbouring factory. The smell inside the club is worse.

Being 16, I can barely believe my luck when I’m granted entry. It would be some time before I realised that Spiders wasn’t merely accepting of minors’ custom, but wholly reliant upon it. I try to get my bearings. Spiders is dark. I mean really dark. To this day I’ve never been to a club that dark; I’m not sure how much it had to do with creating an ambience and how much to do with the owners’ unwillingness to fork out on electricity. After some deliberation I buy myself a Green Monster – an in-house “cocktail”, served in a pint glass – and relax. The music emanating from the dancefloor is some unremarkable Britpop hit or other.

I look at the wall. And then I realise the wall is looking back at me. In fact, the wall is moving. It dawns on me that there are six or seven people leaning against the wall, clad all in black, maintaining a monkish silence, looking distant and more than a little bit tortured. The unremarkable Britpop tune comes to an end, and there’s a brief pause while the DJ fumbles with the controls. Then a new song begins. The song is Sisters of Mercy’s ‘Alice’.

Activated as if by remote control, the sextet of black-clad folk who I’ve mistaken for a wall troop off in the direction of the music, still not uttering a single word to each other. I follow them at a short distance. When I reach the dancefloor they’re there…dancing. Well, I say dancing; more accurately they’re stomping, or sluggishly waving their torsos without moving their feet, or holding their heads in their hands as if in a rapture of pain, or pleasure, or both. It’s like some kind of demented exercise video. Other groups of similarly attired characters arrive at the dancefloor at the same time, and a few of them exchange words, dance together, get off with each other. Then ‘Alice’ stops, and every single one of them returns to the corner of the club they came from, to continue their necking or simply resume brooding in silence.

These characters, you will have gathered, are the Goths.

I’d seen plenty of goths before – they’re an enduring fixture of suburban life – but until this point I’d never witnessed them in their element. It wasn’t pretty, witnessing them in their element, but it was kind of endearing. I’d seen the same folks in daylight, dressed the same way, at bus-stops around town, hoping that their bus arrived before the next torrent of abuse from some lad in a tracksuit. Invariably misfits with low self-esteem, there was undeniable courage in their commitment to the gloomy cause.

That was 1999, and this is 2010. Not a great deal has changed in the interim. To most people goth still represents the epitome of uncool and artistic worthlessness, goths still get beaten shitless at bus-stops, Spiders still sells luminous vodka cocktails to children. But it wasn’t always this way. In the years ’79-’87, when goth was still just a moody outgrowth of post-punk and not yet an indiscriminating global sub-culture and consolation for the socially excluded, it yielded some of the most ambitious and affecting music ever-made.

I’m not a goth, nor was I meant to be. I wasn’t there in ’79-’87. I didn’t live through it. So what follows is an idealised portrait of goth in its infancy. It’s highly selective and at times insensitive. I’ve ignored goth acts who were popular and important to the scene’s development on the grounds that I simply don’t like their music – so no Fields Of The Nephilim, no Mission, no Danielle Dax, etc. I’ve privileged those records that are sonically compelling: as much as goth was about excess, the shadow of Martin Hannett looms heavy over its best records, with minimalist arrangements and cavernous production the going rate. A few of the releases I’ve highlighted could just as easily have found their way into a 20 best industrial, synth-pop, post-punk or minimal wave.

So what, you may ask, do I even mean by “goth”? For the purpose of this list, at least, goth is unfashionable credulousness, sincerity and lack of cynicism. An appeal to higher forces, the dignifying of small emotions with grand imagery. Goth is a return to the poetic; the real post-punk romanticism. But perhaps more than anything…It’s all about the drums. The drums always sound amazing.

Forget the idiots in Camden still caning Sisters CDs and dressing for Columbine. Forget the emo and metal kids who’ve inherited goth’s angst but none of its class. The stylish, experimental, theatrical founding spirit of goth is alive and well elsewhere: in the windswept murder ballads of Zola Jesus, the thumping electronic pop of White Car and Frank (Not Frank), in the decaying electronics of Raime and Leyland Kirby, the kohl-eyed darkwave of Cold Cave. Don’t fear the reaper.

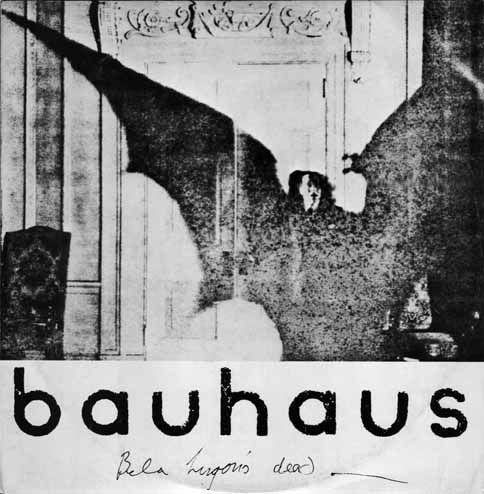

01: BAUHAUS

‘BELA LUGOSI’S DEAD’

(SMALL WONDER 12″, 1979)

Bauhaus embody the escapist, self-dramatizing spirit of goth. Hailing from none-more-bland Northampton and led by rake-thin and androgynously handsome Peter Murphy, the band’s persona erred on the side of pantomime, but their decision to break away from the spartan realist image of punk and its immediate offspring now seems nothing if not bold. Like their hero Bowie, Bauhaus understood the importance of fantasy, and how that’s bound up in the visual: from sleeve art to clothing, make-up to stage lighting. Back when they were first trying to get signed, they issued a video rather than an audio tape to record companies.

Over the course of the four albums that they cut between ’80 and ’83, the musical identity of Bauhaus was stretched in several different directions by its members (sometimes literally: see 1981’s puckish four-part composition ‘1. David Jay 2. Peter Murphy 3. Kevin Haskins 4. Daniel Ash’). There was no such confusion or conflict on their sleek, self-possessed debut single: referencing the Hungarian actor best known for playing the titular Count in Tod Browning’s 1931 Dracula, ‘Bela’ clocked in at an exquisitely arrogant 9 minutes – goodbye to punk’s loaded brevity – and could have justifiably gone on even longer. The loping intro is particularly inspired, ramping up the suspense to an unbearable level as reverbed ghost train FX shudder in and around Kevin Haskins’ bone-dry drums, David J”s descending bassline striated with Daniel Ash’s malevolent swipes of guitar. When Murphy’s campy, crudely overdubbed vocal arrives some two minutes in, you know you’re dealing with one of the all-time great pop singles. “Undead undead UNDEAD!”

02: JOY DIVISION

CLOSER

(FACTORY LP, 1980)

When Steve Coogan’s shellshocked Tony Wilson arrives to visit the body of the recently expired Ian Curtis in Michael Winterbottom’s 24 Hour Party People, he’s button-holed in the chapel’s carpark by a shock-haired, mascara’d and flower-bearing couple who wish to convey how much Curtis meant to them, how he won’t be forgotten. The message is clear, and undeniable: Joy Division begat goth.

Far more substantial and less theatrical than Bauhaus, Joy Division dealt, as you all know, in those themes of existential dread, unresolved love and mortification that would form the backbone of goth mythology. Curtis’s tragic suicide simply sealed the deal: here was a troubled young man whose deathwish was real, not just a parent-bating pose. Moving away from the Ballardian future-shock of Unknown Pleasures, his band charted the sepulchral sublime on their second, final studio album, Closer. The image on the cover – a photograph by Bernard Pierre Wolff of a family tomb in Genoa – makes Curtis’s shift into neo-classical morbidity explicit. The lyrics are correspondingly ur-goth, preoccupied with religion, being and the passage of time. Death, death, death.

No less important to goth was Joy Division’s music itself: not just Curtis’s disconsolate croon, but the high-necked, melody-carrying basslines of Peter Hook, the chicken-scratch guitar of Bernard Sumner, the funereal, oxygen-deprived drums of Stephen Morris. And, most of all, the thing that bound these element together and made them sound as they do: Martin Hannett’s chilly, cavernous production, and subtle, painterly use of synthesizers. This is the sonic template for all the finest post-punk goth records, before the testosterone-fuelled excesses of “gothic rock” took hold.

03: THE CURE

FAITH

(FICTION/POLYDOR LP, 1981)

Following the bittersweet jangle-pop of their debut album, The Cure began to show their true, dark colours on 1980’s Seventeen Seconds. But even that gloomy outing had a new wave airiness and thrust to it; its lead single, ‘A Forest’, positively galloped, its whooshing synths, chiming guitars, desert-dry snare cracks and post-Hooky basslines all locked in kinetic, pistoning alignment. This lingering sense of urgency all but vanished on Faith (1981), the music slowing to the pace of listless suburban life that birthed it.

Rarely, if ever, has music sounded so world-weary. ‘All Cats Are Grey’ is a tactile masterpiece, its sighing keyboard textures and vocal harmonies circumscribed by impossibly funkless drum shots, but also notable is the minor-key chug of ‘Other Voices’, the ceremonial drift of ‘Funeral Party’ and the Gormenghast-inspired ‘The Drowning Man’. The songwriting is superb throughout, the lyrics’ self-pity dignified by the palpable anger of their delivery.

1982’s Pornography went even more goth, but by then the boldly minimalist approach that made Faith‘s despondency resonate had been jettisoned in favour of a more demonstrative and unrefined rock sound.

04: SIOUXSIE & THE BANSHEES

JUJU

(POLYDOR LP, 1981)

“If you study modern groups, those who gain press coverage and chart action, none of them are as good as Siouxsie and the Banshees at full pelt. That’s not dusty nostalgia, that’s fact.” So quoth Morrissey in 1994. The man talks a lot of nonsense (“sub-species”, anyone?) but it’s difficult to argue with this particular judgement.

Born of the ’77-’78 punk explosion, the Banshees recorded three terrific albums – The Scream, Join Hands and Kaleidoscope – before forging their most riveting work, 1981’s Juju. Having already provided the fashion lead for a million goth girls (and a fair few boys to boot), here Siouxsie wheeled out the misanthropic lyrics to match, managing to be elliptical and introspective without compromising on sheer dynamism. Has any song summed up goth’s ghoulish disposition as piquantly as ‘Halloween’? “The carefree days are distant now / I wear my memories like a shroud / I try to speak but words collapse…”

Budgie’s tom-tom-heavy drumming and Steve Severin’s frigid bass work are as compelling as ever, but special mention must go to the choppy, mercurial contribution of journeyman guitarist John McGeogh, who played with Magazine and Visage prior to joining the Banshees and later with Public Image Limited. On Juju he deploys a huge array of string techniques and distortion effects to wring every last globule of sonic potential from his instrument, and all within the tight minimalist grid delineated by Budgie and Severin. The band honed the songs in live performances before going into the studio, and it shows in the fearsome, fat-free recording.

05: THE BIRTHDAY PARTY

‘RELEASE THE BATS’

(4AD 7″, 1981)

Now a fully paid-up member of the dadrock establishment, it takes some effort to remember what a wild-eyed outsider Nick Cave once was. His smack and speed-addled band, The Birthday Party, drew upon schlocky Stateside pop culture, the hostile landscapes of their native Australia and a jumble of repurposed religious imagery to produce some of goth’s most lurid and unhinged music.

‘Release The Bats’ finds them at their most psychotic: a car-smash of ear-splitting, mercilessly trebly guitars, swamp-trawling drums and Cave’s yowling vocal – some distance from the ominous baritone with which he’s now indelibly associated. The title itself is a neat goth clarion call, but the scene is better encapsulated by its lyrical refrain: “Sex horror sex bat sex sex horror sex vampire sex bat horror vampire sex.”

Cave continued to explore gothic themes throughout his career, absorbing more and more influence from Johnny Cash and the old bluesmen (the original goths, perhaps), gradually shedding his more erratic, atonal tendencies for a brand of macabre balladry that would reach its creative and commercial zenith in the 1990s.

06: DANSE SOCIETY

THERE IS NO SHAME IN DEATH EP

(PAX RECORDS 12″, 1981)

At times, goth resembled nothing so much as post-punk gone prog; taking its propulsive dubwise sonics and using them to essay altogether more fanciful ideas. Danse Society’s engrossing 12-minute epic ‘There Is No Shame In Death’ has all the free-form ambition of prog but none of its fustiness and self-conscious virtuosity.

Around Paul Gilmartin’s low-slung drum groove orbit Paul Nash’s scouring guitar, Lyndon Scarfe’s starkly inventive keyboard phrases and Steve Rawlings’ coldly intoned vocals. Each member of the band takes their turn to emote through their chosen instrument, but they never loose sight of their common narrative, and even the synthesizer freak-out which brings the track to a close sounds pensive and hard-earned. Hell, there’s such poise to the composition and the performance here that Rawlings’ dippy lyrics about laceration of the soul, sin and sacrement actually fly, even today. As we’ve already seen, the co-option of religious imagery is a common trope in goth, but nowhere does it sound as bitter and baleful as it does on ‘There Is No Shame In Death’.

An essential 12″, the B-side is given over to the corrosive motorik of ‘Dolphins’ and the zinging art attack of ‘These Frayed Edges’.

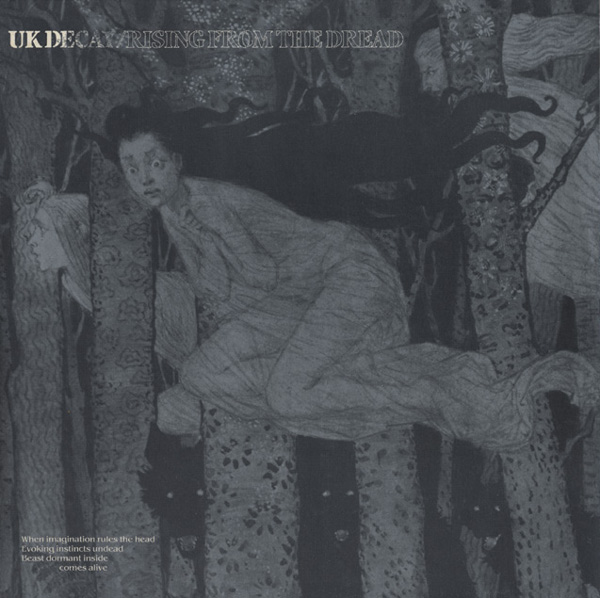

07: UK DECAY

RISING FROM THE DREAD EP

(CORPUS CHRISTI 12″, 1982)

A startling EP from a band described by NME in 1979 as “one of the worst punk bands of all time”, then lavishly praised and held up as “positive punk” forefathers in an ’83 issue of the same publication. UK Decay enjoyed considerable success in the early 80s, and their concertedly muddy, dramatic music influenced Sex Gang Children, Sisters of Mercy and myriad emerging goth pups significantly. Lead track ‘Werewolf’ is signally oppressive: a teeming motion-collage of treacly bass, tightly clustered, tribalistic drums and insectoid guitars that recall the more ferocious passages of Wire’s 154. Into this mire singer Paul Wilson’s rails shamanistically: “When imagination rules the head / Evoking instincts undead /The animal will rise to cry wolf…”

08: SISTERS OF MERCY

‘ALICE’

(MERCIFUL RELEASE 7″, 1982)

Sisters of Mercy, along with The Mission, are among the first bands that people think of when the ‘G’ word comes up; this has as a lot to do with their command of goth imagery, which quickly led to them becoming one of the most visible goth “brands” (I can only imagine how much SoM merchandise has been sold over the past thirty years). Though the majority of their recorded output is wretched, in their early years SoM were pretty compelling, combining the primality of metal with the polysexual pulsation of what would come to be known as EBM; their finest creation in this vein was the dark-wave floor-filler ‘Alice’.

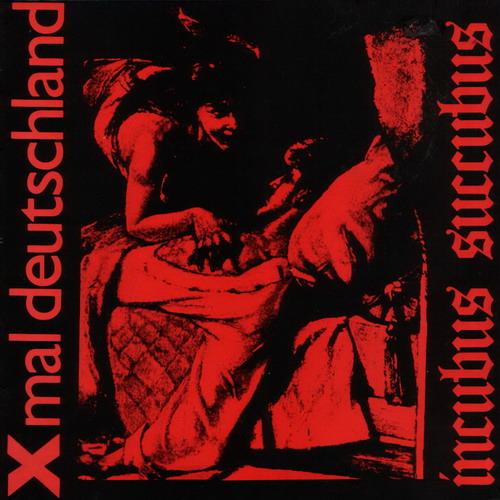

09: XMAL DEUTSCHLAND

‘INCUBUS SUCCUBUS’

(ZICKZACK 12″, 1982)

Almost needless to say, German youth took to goth in a big way. Hamburg’s own Xmal Deutschland caused quite a stir here in the UK, striking gold with their second single, 1982’s malevolent, haranguing ‘Incubus Succubus’. DIY goth par excellence, its success led to a deal with 4D that in turn gave rise to the fine albums Fetisch and Tocsin; even with studio polish, Xmal’s music – characterised by Fiona Sangter’s keyboards, Anja Huwe’s flatly insistent vocal and the droning, one-note guitar parts of Manuela Rickers – remained proudly lean and lo-fi. Though goth first and foremost, they were a crucial part of, and influence on, the minimal wave.

10: VARIOUS ARTISTS

YOUNG LIMBS AND NUMB HYMNS

(LONDON RECORDS LP, 1983)

The Batcave was the epicentre of goth nightlife in its leather ‘n lace-laden pomp, and can now be seen as part of the no-effort-no-entry lineage of London trashionista parties that also includes Taboo, Nag Nag Nag, Kashpoint, Boombox et al. The club opened in July 1982 on Meard Street, Soho – an appropriate setting, given the obvious influence of cabaret grime and glamour on its denizens. Beginning life as an ill-defined new wave concern, it was run by Specimen’s Ollie Wisdom and Jon Klein (tellingly, Specimen keyboardist Jonny Slut went on to co-found Nag), the emerging sounds of goth and darkwave gave it its true and lasting identity. The place to be and be seen, its elaborately decked-out punters took the title of Specimen’s ‘Stand Up Stand Out’ as a sartorial instruction; the likes of Nick Cave, Robert Smith, Siouxsie Sioux and JG Thirlwell (Foetus) could be spotted in amongst the haircuts.

Released on vinyl in ’83,Young Limbs And Numb Hymns was a compilation which aimed to capture the spirit of the Batcave; its manic diversity is a sign of how unconstrained and open-ended goth was at the time: the theatrical shock-rock of house band Specimen and soaring punk-pop of Sexbeat rubbing shoulders with the sturm und drang industrial of Test Dept and the breathtaking (and breathtakingly OTT) chamber music of The Venomettes. The latter group were a classically trained string ensemble who lent their talents to recordings by Marc & The Mambas among others; this LP is worth owning for their eldritch contribution (‘The Dance Of Death’) alone, and of course the sleeve notes, which I can’t resist quoting in full:

“Look past the slow black rain of a chill night in Soho; Ignore the lures of a thousand neon fire-flies, fall deft to the sighs of street corner sirens — come walk with me between heaven and hell. Here there is a club lost in its own feverish limbo, where sin becomes salvation and only the dark angels tread. For here is a BATCAVE. This screaming legend of blasphemy, Lechery, and Blood persists in the face of adversity. For some the Batcave has become an icon, but for those that know it is an iconoclast, it is the avenging spirit of nightlife’s badlands — its shadow looms large over London’s demi-Monde: It is a challenge to the false Idol. It Will Endure.”

11: KILLING JOKE

REVELATIONS

(POLYDOR LP, 1982)

Killing Joke’s gothic rock grew exponentially more sludgy and brutal with each passing album; by the mid 80s they were basically a metal band. Their development mirrored that of goth at large: a steady descent into the kind of macho, constipated heaviness that still characterises the genre today, at least in the eyes of outsiders. Still, their early records were terrific: particularly their third, Revelations, which they recorded with krautrock overlord Conny Plank. During the making of the album the band immersed themselves in the occult, succumbing to the paranoia that such an obsession inevitably yields, especially when paired with heavy drug use. In 1982, singer Jaz Coleman moved to Iceland, in order to survive the imminent apocalypse, with his bandmates following soon after. The apocalypse never came, and Killing Joke duly lost their mojo.

12: VIRGIN PRUNES

PAGAN LOVESONG

(ROUGH TRADE 7″, 1982)

Some of the best goth was dance music – 4/4 rock ‘n roll made for the local disco, that ill-lit barnyard where you could meet and cop off with fellow freaks, or at least compare your latest make-up tips. Virgin Prunes’ ‘Pagan Love Song’ was a smash on goth dancefloors, and it’s easy to see why. Gavin Friday’s lyrics (“I want to steal your heart / I want to eat your heart”) hover over a hypnotic rhythm and a scooping, downtown ’81 bassline, and there’s even a techno-style breakdown midway through. The abrupt finale – a shiver of white noise and a suspended tribal drum tattoo – is in itself worth the price of admission. Chief Prune Gavin Friday never thought of his band as goth, seeing them more as an authority-bating art project, and they frequently took the meaning of “performance” to COUM-like scatological extremes.

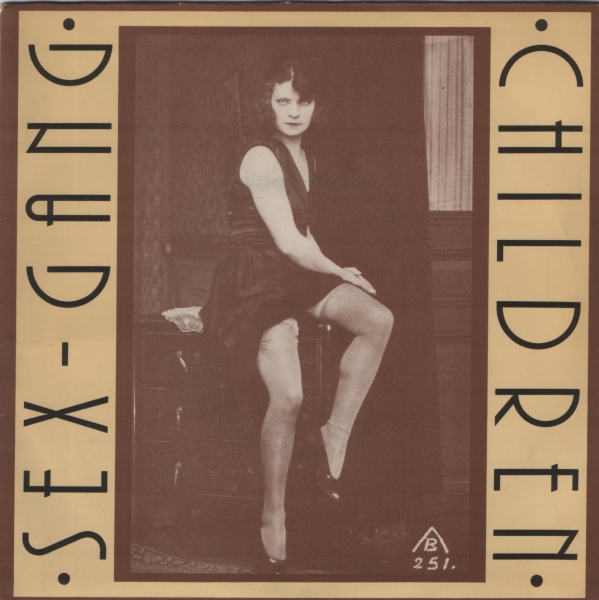

13: SEX GANG CHILDREN

‘MAURITIA MAYER’

(CLAY RECORDS 7″, 1983)

Emerging out of the Batcave scene, Sex Gang Children’s nightmare cabaret music is distinctive and fully-realised enough to ensure their immortality in goth lore, despite their having only ever released one proper album. Listening to the band’s first vinyl offering, the Beasts EP, evokes the feeling of being in a club aged 15, having had one shot of sambucca too many and lost your mates, staggering around looking for somewhere to vomit and pass out. They cleaned up their sound a little bit for the aforementioned Song And Legend album, but their most accessible work – and highest charting effort – was the 1983 single ‘Mauritia Mayer’, Andi Sex-Gang’s withering whine playing second fiddle to phased new wave drums and keyboards.

14: RUDIMENTARY PENI

DEATH CHURCH

(CORPUS CHRISTI LP, 1983)

Including this might seem perverse, as the Peni initially sprung from the anarcho-punk scene, the deeply politicised, deeply sexless schtick of which goth defined itself against. But the Peni were a different kettle of vegan fish to Crass, learning from the militant simplicity and brevity of that group’s music but using it as a means to explore more florid and fantastical lyrical themes – their ’87 album Cacophony was a sonic tribute to HP Lovecraft, which tells just how far from squat reality they’d wandered. Nonetheless, Death Church is goth-rock at its most muscular and least self-indulgent, its message of doom and disaffection virulent and all-consuming.

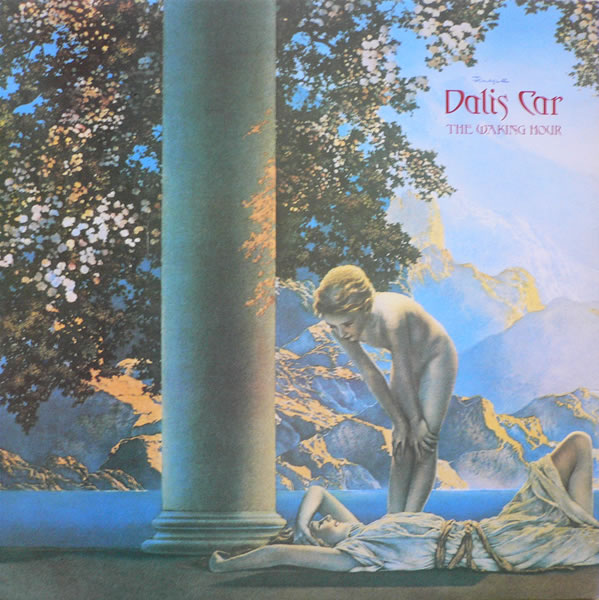

15: DALI’S CAR

THE WAKING HOUR

(PARADOX RECORDS LP, 1984)

With the possible exception of ‘Dark Entries’, no Bauhaus track ever matched the power and poise of ‘Bela Lugosi’s Dead’. But the band’s members would enjoy a degree of success in some, if not all, of their post-Bauhaus projects – Daniel Ash’s Love And Rockets weren’t much cop as far as I’m concerned, but check out his more short-lived and experimental project Tones On Tail, whose work for the 4AD, Situation Two and Beggars axis spanned the Eno-influenced dream-pop of ‘Rain’ and the oddly breaker-friendly electro concréte of ‘Shakes’/’Performance’. Peter Murphy enjoyed commercial impact with his solo releases, but there’s a good deal more artistic worth to his lone full-length collaboration with Mick Karn as Dalis Car. Karn was bassist in Japan, whose own proto-goth synth-pop initially paralleled but soon far outclassed that of Bauhaus.

A truly imaginative and talented musical mind, Karn was occasionally too virtuoso for his own good, over-crowding records with his lugubriously funky playing, and this self-indulgence certainly ruins much of Waking Hour. On pieces like ‘Cornwall Stone’, though, Karn applies more attention to framing Murphy’s vocals with droning synth textures, and the effect is quite magical. As with most of Murphy’s work, it’s difficult to defend the charge of pretentiousness – right down to the painting of the prone neo-classical nymph that adorns the album’s lavish gatefold cover, and comes courtesy of cult American painter Maxfield Parrish. Dalis Car, like Parrish, risk absurdity in their explicit longing for an archaic, otherworldly sublime; a risk worth taking.

16: CHRISTIAN DEATH

CATASTROPHE BALLET

(L’INVITATION AU SUICIDE LP, 1984)

Leading lights of deathrock, a blunt Stateside rebranding of goth, Christian Death are best known for their 1982 debut album (Only Theatre Of Pain. But my favourite is the curiously European-sounding follow-up, Catastrophe Ballet, an altogether more elegant and less strained achievement than its predecessor. Singer Rozz Williams is joined by a completely different band to the one that served him on Theatre, and his own belligerent bark has matured into a velvety croon audibly inspired by David Bowie and Lou Reed. Though not without its flaws, the breadth of the band’s ambition here is stunning: taking us from the late night Weimar balladry of opener ‘Awake At The Wall’, through the tumbling metal reverie of ‘The Blue Hour’ and the industrial glide of ‘The Fleeing Somnambulist’. Great sleeve too, apparently inspired by one of Rozz’s mushroom trips.

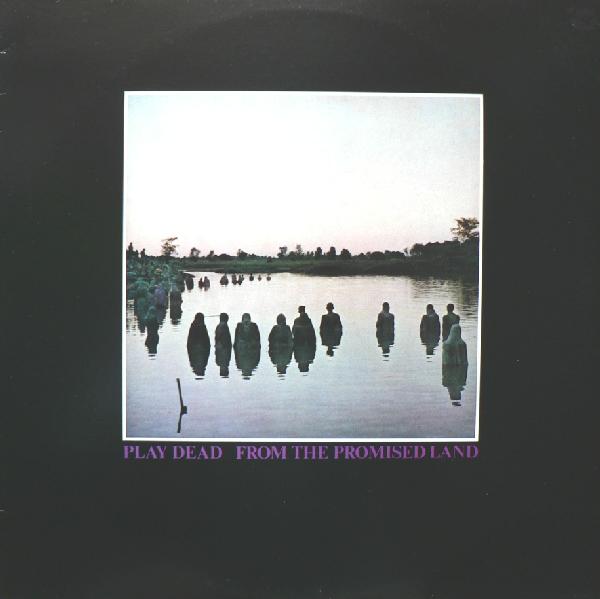

17: PLAY DEAD

FROM THE PROMISED LAND

(CLAY RECORDS LP, 1984)

Like so many bands in this list, Play Dead hated the “goth” tag – even though everything about them, from the music itself to their morbidly romantic cover art and song titles seemed to passionately invite it. However you want to categorise it, what can’t be contested is that From The Promised Land is a tremendous rock record, driven by Re-Vox’s crunching, full-bodied riffs, Mark ‘Whiff’ Smith’s thunderous drums and Rob Hickson’s hectoring voice (divine in spite of its unnerving likeness to that of Kings of Leon’s Caleb Followill). Still, there’s nothing trad about it: witness the skittering echo effects on ‘Torn By Desire’ or the elasticated punk-funk bass of ‘Holy Holy’. The album’s finale, ‘Weeping Blood’, rivals The Doors for sand-blasted, messianic gusto.

18: CINDYTALK

CAMOUFLAGE HEART

(MIDNIGHT MUSIC LP, 1984)

Cindytalk’s singer and mainstay Gordon Sharp contributed to This Mortal Coil’s Sixteen Days/Gathering EP and It’ll End In Tears album, but his own debut LP, Camouflage Heart, was all about the guttural, not the ethereal. Though ther eare some passages of prettiness – Sharp would develop these more fully on subsequent instrumental, piano-led (and altogether more dull) Cindytalk records – Heart is black to its very core, defined by its choppy, overdriven guitar parts, strangulated vocals and dark ambient drones that would have Lustmord reaching for his teddy bear. Disintegration is a recurring theme in the lyrics, and the music – a fraught meeting of the eldritch and the industrial – enacts it, seeming to crumble before one’s very ears. After spending much of the 1990s immersed in the techno underground, Sharp has recently revived Cindytalk as a digital noise project, releasing new work on Vienna’s esteemed Editions Mego imprint (home to Pita, Fennesz, Emeralds, Oneohtrix Point Never et al).

19: AND ALSO THE TREES

VIRUS MEADOW

(CLAY RECORDS, 1986)

Hailing from the tiny village of Inkberrow, deep in the Worcestershire countryside, And Also The Trees were motivated by the sonic vigour of post-punk but refracted it through their own rural identity. The resulting music is unwaveringly nutty and often beautiful, spanning feather-light dream-pop, echo-drenched rock ‘n roll and bloodthirsty chamber-folk, all united by the hammy voice of Simon Huw Jones.

Their fine self-titled debut album was produced by The Cure’s Lol Tolhurst, and sounds like it. On their sophomore effort, 1986’s Virus Meadow, they established their own unique musical fingerprint, using dub-infused atmospherics to complement Jones’ increasingly lofty lyrical content, a hysterical and imagistic extension of British folk’s darkest themes. “Creating an ambience is very important,” remarked guitarist (and Simon’s brother) Justin Jones in 1985. Nowhere do the band better achieve this than on the masterfully tense ‘The Headless Clay Woman’, which to my ears at least presages the occult-tinged post-rock of Slint.

And Also The Trees remain an extraordinarily hard band to categorise, which perhaps explains why they seem to have been squeezed out of the art-rock canon, a travesty which we can but hope will be rectified in due course.

20: DEAD CAN DANCE

WITHIN THE REALM OF A DYING SUN

(4AD, 1987)

Dead Can Dance took goth’s fascination with the religious and ritualistic to bombastic extremes. Their self-titled debut of 1984 is more contemporaneous with most records on this list, but its tribalistic post-punk sound is, for the most part forgettable. On 1986’s Spleen And Ideal DDC began to fulfil their more grandiose ambitions, musically and lyrically; the instrumentation is neo-baroque, all dolorous brass, peeling guitar and bell-tones adrift in a wash of synthesizers and Celtic-flavoured choral drones (led by the initimable Lisa Gerrard). They groomed and grew this aesthetic to perfection on 1987’s Within The Realm Of A Dying Sun, this time constructing even more ambitious harmonies and arrangements. The album opens with ‘Anywhere Out Of This World’, a towering, Brendan Perry-sung torch song that represents goth’s most cinematic moment; other highlights include the spooked orchestral instrumental ‘Windfall’.

The true fate of goth by 1987 was the dick-swinging, brainless gothic rock churned out by Sisters Of Mercy, The Mission and their legion descendants, but its original spark of invention, romanticism and, well, gloom – the qualities that this list has aimed to locate and champion – survived, albeit expanded and adapted, in the music of Dead Can Dance and their emerging dream-pop peers.