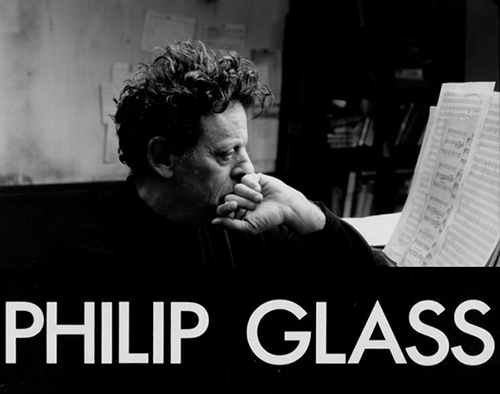

Though he’s not without his detractors, it’s impossible to deny Philip Glass’s gigantic presence in, and inestimable impact upon, 20th century music.

We approach Glass’s oeuvre here today principally for our interest in the ways it has influenced, and been influenced by, electronic music. The impression his work made on Brian Eno, Tangerine Dream and later Aphex Twin is already well-documented, but its reach extends further forward into time. Just this week we reported on Oneohtrix Point Never’s new remix of Glass’s Koyaanisqatsi title theme, commissioned – but ultimately rejected – for a forthcoming remix project celebrating the composer’s 75th birthday. Curated by Beck Hansen, the compilation features contributions from the likes of Tim Hecker, Amon Tobin and Tyondai Braxton, and highlights the esteem in which Glass is held by yet another generation of younger artists. One suspects that in another 25 years his stature and perceived relevance will be undiminished, perhaps even increased.

Born in Baltimore in 1937, Glass is indelibly associated with New York City, where he has been based since the mid-50s, and in whose downtown ferment of interdisciplinary art and performance he first rose to prominence. He was alive from the off to the liberating possibilities of overdubs and looping strategies, and of electronic music technology in general – being an early adopter and advocate of portable Farfisa organs, polyphonic synthesisers, Midi computer systems, keyboard controllers and samplers.

In this list see how Glass’s considered embrace of the new – not least his cellular, cyclical approach to composition, which was informed by his work with Ravi Shankar and would come to completely revolutionise Western music – has manifested itself on record. We also learn how his iconic status can be at least partly attributed to the skill, and flair, with which he’s marketed his music and himself.

Ravi Shankar

Chappaqua

(CBS LP, 1966)

In 1966, Glass – Phil Glass, as he’s credited in the sleeve notes- was invited to help out with Ravi Shankar’s soundtrack for Conrad Rooks’ delirious beatnik drug movie Chappaqua, in which the likes of William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Moondog and Ornette Coleman appeared. As Mark Prendergast explains in The Ambient Century, Glass was tasked with transcribing Shankar’s music for Western musicians to play, and had to write directly from the Indian’s vocal dictation.

After trying, and failing, to capture Shankar’s unique phrasing through conventional notation, Glass decided to dispense with bar lines, observing that “instead of distinct groupings of notes, a steady steady stream of rhythmic pulses stood revealed”. This is the key formative moment in Glass’s career, inspiring the cellular, cyclical approach to composition that would characterise his most famous and innovative works.

Philip Glass

Music With Changing Parts

(Chatham Square Productions 2xLP, 1971)

Presumably encouraged by the DIY derring-do of the downtown artists he was mixing with at the time, Glass circumvented classical music’s traditional channels with the manufacture and release of his first recorded work, Music With Changing Parts, through his own “semi-private” press, Chatham Square Productions.

Even bolder, and cannier, was his decision to assume the role of recording artist as well as composer – though he maintains that this was a strategy for survival, a way of getting noticed, in time it has obviously proved to be a lucrative one as well. Music With Changing Parts introduces the idea of Glass as “rock star”, whose own studio albums and live performances, not others’ interpretations of his work as written, are seen as definitive. Put another way, the image of the artist is inseparable from his art: an icon, or less charitably speaking a brand, is born.

Chatham Square lasted until 1977, during which time it released music not only from Glass but also Richard Landry, John Gibson, Michael Snow and a certain Arthur Russell – needless to say, everything on the label is highly collectible, and a mint copy of the original Music With Changing Parts gatefold will set you back well over £100.

Philip Glass

Music in Twelve Parts – Parts 1&2

(Caroline LP, 1974)

If you want to cut right to the quick of what Philip Glass’s music is about, seek out a copy of this edition, issued on Virgin’s budget Caroline imprint in ’74. Excerpted from a sprawling work that wouldn’t receive a full release until 1988, the two sides are based around techniques and motifs that Glass has returned to again and again – solfège vocals, drizzling arpeggios, plaintive woodwind. ‘Part 1’ is particularly engrossing, with a slow, psychedelic drift that makes it feel like a close cousin of the kosmische music that was emerging from Germany around the same time.

Philip Glass

Solo Music

(Shandar LP, 1975)

Solo Music was always assured a place on the list, for the fairly shallow reason that it was released on the outrageously cool – there is no other word for it – Shandar label, which was founded in France by Chantal Darcy and Daniel Caux and released highly covetable editions of work by Terry Riley, Pandit Pran Nath, Cecil Taylor and Albert Ayler, among others. André Belligue’s crisp, pellucid sleeve design is worth the price of admission alone.

The music? Well, it’s some of Glass’s most radical and sternly minimalist work. Conceived around ’68-’69, ‘Two Pages’ is born out of the composer’s Shankar-informed technique of “additive process”, and explores “the elongation and subsequent contraction of a simple musical line”. ‘Contrary Motion’ was written in what Glass calls “open form” – the expanding figures which it’s built out of “could, theoretically, continue augmenting forever”.

Philip Glass / Robert Wilson / The Philip Glass Ensemble

Winstein On The Beach

(Tomato 4XLP Box Set, 1979)

Released on legendary New York independent Tomato – which in its 70s pomp provided an outlet for artists as diverse as Jon Hassell, Albert King, John Cage and Annette Peacock – this 4xLP set is the definitive edition of Glass’s first and best opera, which was designed and directed by fellow downtown shaker Robert Wilson. Einstein On The Beach is less a biographical study of its titular hero and more a meditation on time, space and man’s place within it, eschewing traditional narrative structure in favour of a digressive, poetic, at times hallucinatory approach. At over 4 hours long, you might deem psychedelic drugs necessary to get you through it.

Philip Glass

Glassworks

(CBS LP, 1982)

Glassworks was the album that really established Glass as a unit-shifting phenomenon. The faintly new age cover imagery is telling: the commercial success of Glass in the 1980s had largely to do with the way his work was marketed as chill-out music for baby boomers; the short, pop-length pieces on Glassworks constituted an album of “safe” experimentalism to sit alongside Dark Side Of The Moon in the CD racks of aspirational city flats throughout the western world. Though occasionally mawkish, there’s some extraordinary music on here – particularly ‘Floe’, a coolly controlled dervish of woodwind and electronics that was sampled to great effect by Ricardo Villalobos on his 2005 track ‘Morphunk’.

Philip Glass

Koyaanisqatsi

(Antilles LP, 1983)

Glass composed this music for Koyaanisqatsi (Hopi Indian for ‘life out of balance’), an experimental 1983 documentary by Godfrey Reggio – remarkably, the film was edited to Glass’s score, rather than the other way around. Perhaps it’s easy to see why: from the driving, dramatic orchestral movement ‘Pruit Igoe’ to the more cyclical, meditative variations on ‘Floe”s melodic theme, Glass’s compositions here have a cumulative, mathematical intensity that demands not to be disrupted.

Philip Glass

Low Symphony

(Point Music CD, 1993)

Glass’s attempts to engage with pop forms haven’t always come off – 1983’s Songs For Liquid Days, based on lyrics by David Byrne, Suzanne Vega, Paul Simon and Laurie Anderson, being his most high-profile creative disaster.

Interestingly, his successes in this field have occurred when he’s tackled more obviously electronic music – as in his orchestration of Aphex Twin’s ‘Icct Hedral’ for the Donkey Rhubarb EP (Warp, 1995), or his symphonic sketches based on David Bowie’s Eno-midwifed Low and “Heroes”. Of the Bowie/Eno tributes it’s the former that’s most worth hearing, if only because it highlights the unimprovable grandeur of the originals – ‘Subterraneans’, ‘Some Are’ and ‘Warszawa’.

With the release of Low Symphony, a circle was completed. Some 22 years earlier, Bowie and Eno had been present at a performance of Music In Changing Parts at London’s Royal College Of Art, an experience which must surely have influenced their groundbreaking work together.

Philip Glass & Ravi Shankar

Passages

(Private Music LP, 1993)

Glass and Shankar’s long overdue reunion took place in 1993, 27 years after they worked together on Chappaqua, and yielded this supremely satisfying fusion of Indian and Western styles – recorded in New York and Madras, and released on Private Music, the label run by Tangerine Dream’s Peter Baumann. Shankar and Glass contributed three originals apiece, and it’s really quite remarkable to hear how blurred the two composers’ styles are – the Shankar-penned ‘Offering’ sounds even more Glass than Glass, and until you check the credit you’d swear that Glass’s ‘Sadhanipa’ has poured straight from the heart of Shankar.

Kronos Quartet, Philip Glass

Kronos Quartet Performs Philip Glass

(Nonesuch CD, 1995)

In which the Kronos Quartet bring to life four Glass string quartets written between the mid-80s and early 90s. These five suites – which include commissions for Paul Schrader’s film Mishima and a Fred Neumann stage adaptation of Samuel Beckett’s Company – are among Glass’s more traditional compositions, but still possessed of the oscillating, additive energy that drives his more feted pieces. String Quartet No.5, which opens the disc, is surely his most ravishing and lyrical work to date.