Available on: Republic

Decidedly class of ’94 in sensibility, Angel Haze’s 2012 mixtape Reservation featured an earthy production style that was, for want of a better word, real: tactile, naturalistic and unadorned. In this way it served as the perfect housing, affording the record a sense of honesty during Haze’s thoughtful confessionals (on which Eminem was a primary influence) and edge during its gritty street-level bangers. Haze’s debut proper Dirty Gold, however, takes a different approach. It’s a pop record. And it’s a failure.

Like many rappers before her, Haze’s attempt to combine underground values with commercial appeal, but also maintain her identity, results in a disjointed aesthetic. Reservation was produced with a refreshing uniformity in an era where many rap albums are made like best of compilations – producer samplers with no regard for aesthetic consistency – mostly because its production was consistent with Haze’s message. She possesses a strong individual identity, which the production seemed to be built around. It was a throwback to the culture that produced Illmatic, where an album’s production was a natural extension of a rapper’s worldview.

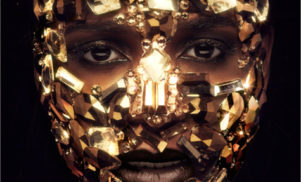

Dirty Gold, a title in reference to the album’s combination of grit and gloss, is wrong from the off, with a loathsome opening trio of cuts forming Haze’s big play for the charts. Featuring 30 seconds or so of rapping but a shit-ton of Guetta-esque synths and pop choruses, on ‘Sing About Me’ Haze is almost unrecognisable from the artist showcased on Reservation. Gone is the granite austerity, the danger, the soul.

‘Echelon ‘(It’s My Way)’ follows. Indistinguishable from ‘Sing About Me’ sonically, it also features the kind of trite braggadocio that seemed to be beneath Haze, who on her past mixtapes couldn’t have been unoriginal if she tried. Ironically, the song is all about the importance of doing your own thing. And although ‘A Tribe Called Red’ is structured to allow for some of the best rhyme-rage in mainstream female rap since Lil’ Kim, it’s the song’s horrible brostep production that dominates.

The production on Dirty Gold – generic, consistently uninspired, gauche – bears absolutely no relation to the album’s subject matter, and jars horribly with Haze’s dark forceful flow. Her balance of strength and vulnerability is rendered caricature, polarized: she’s either grunting nihilistically over mawkish balladry or mewing softly over hard Luger-style FX. Meanwhile, against the gaudy and saccharine backdrop of many of these tracks, her woes are rendered soap opera and Haze herself shrill. The record’s nadir, ‘Angels and Airwaves’ finds Haze addressing the subject of suicide over a fluffy backdrop of tinny flyover-state pop-rock.

Eminem is again a key reference point on Dirty Gold, though this time Mathers’ influence is a negative one, with Haze’s complaints and ire verging on melodramatic – taking after Eminem in his post-Relapse form. On the chest-thumping likes of ‘Black Dahlia’ – employing the Mathers format of lug-headed bombast + self-pity + Youtube pop (think ‘Monster’) – Haze’s bullish aggression, which once conveyed power, seems now undignified, indignant and, worst of all, haranguing.

The confessionals are equally compromised. Take ‘Rose Tinted Suicide’: instead of letting Haze’s words do the talking – as with how her troubles were presented on Reservation – here a gallery of chart producers shit all over the song’s sombre heart with strings, dramatic beats and heavenly choirs. There’s almost a bit of Nine Inch Nails to Dirty Gold, in the way that Reznor’s torment tends to result in heavy-handed emoting and blustery theatrics. In addition, Haze often sings (sung choruses are a frequent occurrence), and in a sweetheart, girlish way, resulting in a host of tracks that just sound disposable. ‘Planes Fly’, with its grand piano part and big moments and lyrics about spreading your wings and flying, is pure American Idol fodder. In the end, it’s only ‘Battle Cry’ that, in spite of its cheap sentimentality and easy platitudes, manages a sense of gravitas.

Although ‘Crown’ is able to combine hooky chart lustre with some of the swaggering belligerence featured on Haze’s calling card ‘New York’, the production across Dirty Gold is ultimately blaring white noise drowning out the inner voice that Haze seemed, amongst her dance-rap contemporaries, alone in having. Where’s the conflict, the self expression, the sense of struggle? I hate to say it, but where’s the soul?