The great electronic albums of the 1970s get plenty of kudos – but what of their predecessors?

Casual accounts of the history of electronic music tend to point back to familiar sources: Suicide’s babble’n’hum; Cluster, Klaus Schulze and the rest of the Krautrock squad; the stygian mulch-music of early Cabaret Voltaire and Throbbing Gristle; and of course Kraftwerk’s meticulous robot pop. Further back? Well, that’s when things tend to get a little foggy.

Experiments with recorded electronic music actually date back to the 1940s (hell, depending on how you define “electronic music”, they date back to the 1880s). As early as the mid-1950s, predominantly electronic LPs were already being pressed, marketed and sold to a willing (if slightly confused) public. Half a century down the line, many of these records still sound fantastic. Some are fascinating relics with plenty to say to the contemporary listener; others sound impossibly ahead of their time.

The following rundown is limited to complete artist albums, as opposed to compilations or collections of stand-alone works. As such, important names perhaps more readily associated with the realm of “art music” – Pierre Schaeffer, Pierre Henry and the GRM sect; Edgard Varèse; Karlheinz Stockhausen; Iannis Xenakis; James Tenney; Alvin Lucier; Luciano Berio and plenty more – are respectfully put to one side. Similarly, dear quibblers, “electronic” has been broadly taken to refer to albums that put new synthesizer instruments or synthesized tones at their core. By that token, some exceptional albums (Terry Riley’s organ masterpiece A Rainbow In Curved Air; Steve Reich’s Live / Electric Music) are omitted, and rock and pop LPs that flirt with electronics without going the whole hog have also been left out.

Ground rules set – and inevitably occasionally broken – here they are: 15 essentials from electronic music’s Big Bang.

Kid Baltan & Tom Dissevelt

The Fascinating World of Electronic Music

(Philips, 1959)

Some canny YouTube user has tagged a track from The Fascinating World of Electronic Music as “acid house from 1958”, clocking up a quarter of a million views in the process – and, as it happens, they’re not too far off the money.

Kid Baltan is the alias of Dutch artist Dick Raaijmakers, a cultural theorist, musical theatre composer, lecturer and engineer, whose whopping output stretches deep into the 2000s. Tom Dissevelt, meanwhile, started his musical life in big bands and orchestras – a similar situation to first-wave innovators like Raymond Scott, whose work as a composer appeared in the Looney Tunes cartoons, and various members of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop.

Raaijmakers and Dissevelt crossed paths working at Royal Philips Electronics, the Eindhoven-based workshop that would eventually churn out the first cassettes and compact discs. There, the pair started producing speculative electronic pop music, built out of layered oscillator tones and acoustic sound sources. Their labours produced 1957’s ‘Song of the Second Moon’ – a propulsive track based around treated Ondes Martenot noises, and arguably the first electronic pop record ever made.

Baltan and Dissevelt’s music from this period was released in numerous editions and under different guises, but The Fascinating World of Electronic Music is the first release to pull their late 1950s compositions under one roof. The results – giddy, chirruping electronic pieces, arranged like pointillist dot paintings with a keen sense of rhythm – are still killer. Remarkably, much of these were also produced without any sort of keyboard or synth to hand. Raaijmakers’ legacy hasn’t been forgotten – Thurston Moore and Mouse on Mars are among those to have reinterpreted his work

See also:

Herbert Eimert – Einführung (Deutsche Grammophon, 1957)

A passionate proponent of ‘pure’ electronic music, Eimert was the first director of Cologne’s hugely important Studio for Electronic Music. This early 10″ collection of beguiling machine mutterings is sometimes featherlight, often chilling.

Various Artists – Popular Electronics: Early Dutch Electronic Music From Philips Research Laboratories (1956 – 1963) (Basta, 2004)

Gargantuan overview of early material from the Philips Electronics lab, featuring work from Raaijmakers, Dissevelt and Henk Badings.

Perrey-Kingsley – The In Sound From Way Out! (Vanguard, 1966)

Lounge, bossa and yé-yé in The Happening Electronic Style, with added Ondioline. Cue montage of C-3PO pottering down Carnaby St.

White Noise

An Electric Storm

(Island, 1969)

White Noise were BBC Radiophonic Workshop icon Delia Derbyshire and classical bass player (and Derbyshire’s romantic partner) David Vorhaus, with added input from Derbyshire’s Unit Delta Plus associate Brian Hodgson. Really, though, the main spark behind An Electric Storm was Island Records boss Chris Blackwell, who slung these boffins £3000 to make a chart-friendly record steeped in experimental electronics. The punt paid off, creatively if not commercially – An Electric Storm is the exhilarating sound of experimental talents being given the keys to the city, and proceeding to paint it fifty shades of red.

An Electric Storm is pure Willy Wonka music – rich, maximal psych-pop, full of studio tricks and sleights of hand. Cheery (and sometimes cheesy) pop constructions are interrupted by blasts of horrid interference, or disintegrate entirely without warning. Filtered drum patterns twist, turn and mutate; pretty vocal lines – by Val Shaw and Annie Bird among them – are interrupted by strange industrial clangs (the kitchen sink being tossed in, presumably). Orchestral arrangements turn out to be layered bass parts, variously pitched up and down to resemble violins and cellos. Scorched earth exotica (‘Love Without Sound’), mangled doo-wop (‘Firebird’), and seventh-circle smut (‘My Game Of Loving’) – An Electric Storm is the sound of powerful imaginations going into overdrive.

See also:

Joe Meek – I Hear A New World (RPM, 1991)

Recorded in 1959 and covertly circulated ever since, I Hear A New World is one of the great early electronic pop albums – space-age skiffle, swamped in reverb and stretched beyond recognition by Meek’s innovative studio techniques.

Lothar & The Hand People – Presenting…Lothar and the Hand People (Capitol, 1968)

Twangy psych-rockers, fronted by a cheery Theremin called ‘Lothar’ – presumably better behaved than most telly-flinging frontmen of the era. Notable for their early use of the Moog in a psych-rock context.

The United States Of America – The United States Of America (Columbia, 1968)

How many John Cage students does it take to change a lightbulb? God know, but put them in a room with a stack of ring modulators, treated ‘electronic’ drums and a homebuilt Durrett Electronic Music Synthesizer, and they’ll turn out one of the most venturesome rock records of the late 1960s.

Silver Apples

Silver Apples

(Kapp, 1968)

Silver Apples is, in sensibility and intent, a straightforward rock record – it just happens to be played on one of the weirdest electronic set-ups imaginable. Inspired by Sun Ra, NY musician Simeon Coxe cadged an oscillator off a friend, and learned his way around it by playing along to Rolling Stones records in his bedroom. Before too long, his garden variety rock’n’roll covers outfit had been transformed into a two man drums’n’oscillators beast, and one of the great cult bands of the era.

Silver Apples’ set-up centred around The Simeon – a gargantuan equipment rig that puts Rick Wakeman’s keyboard encampments to shame. The Simeon featured multiple pre-tuned oscillators routed through a telegraphy key, which Coxe then controlled using his feet, hands and, where required, forehead. Fuzz units, phasers and treated speakers were than bolted on to add character and texture to the sound. It was, by all accounts, a chaotic and haphazard set-up, and one that took many hours to set-up and dismantle.

Recorded in a four-track studio, the band’s debut album is a stunning collection of rickety electronic grooves and hydraulic wheezes – the sound of a steam-train chuffing off into the stars. Given the difficulty of achieving polyphony with an oscillator set-up, the compositions are often harmonically static, giving the record a driving, hypnotic quality. There’s not a bum track on it, and the best – ‘Oscillations’, ‘Lovefingers’, ‘Program’ (one of the first tracks of its kind to sample a radio broadcast) – combine rhythmic swagger with some good old twilight-of-the-Sixties paranoia. Suicide wouldn’t – couldn’t – exist without them.

See also:

Fifty Foot Hose – Cauldron (Limelight, 1968)

San Fran outfit with links to the iconic Mills College Tape Music Centre, and another outfit using homebuilt synthesizers within a rock idiom.

Fred Weinberg – The Weinberg Method Of Non-Synthetic Electronic Rock (Anvil, 1968)

Heavy on the synthesizers and spotted with little concrète flourishes, this breezy collection has plenty to recommend it – a cheerier alternative to Silver Apples‘ pulsing intensity.

Ron Geesin – A Raise of Eyebrows (Transatlantic Records, 1967)

Composer/goofball Geesin remains best known for his work on Pink Floyd’s Acid Heart Mother, but this debut solo LP navigates an enjoyable path between electronic tomfoolery, hippy-dippy songwriting and Goons-indebted wackiness.

Jean-Jacques Perrey

Prelude Au Sommeil

(Procédé Dormiphone, 1958)

Jean-Jacques Perrey is principally known for his Moog recordings, whether working alone (1968’s The Amazing New Electronic Pop Sound Of Jean-Jacques Perrey) or in collaboration with Gershon Kingsley (1968’s furiously chipper The In Sound From Way Out). A famously colourful character, he’s worked with Walt Disney, been sampled by DJ Premier, and made a version of ‘Flight Of The Bumblebee’ with real bee sounds that everyone should hear at least once. Prior to that, though, Perrey was an early proponent – and arguably the great virtuoso – of the Ondioline, a proto-synthesizer from the 1940s.

Built by George Jenny, the Ondioline was a monophonic vacuum tube keyboard, encased in a plush wooden cabinet. The keyboard was mounted on springs, meaning the keys could be physically wobbled to create a vibrato effect whilst playing. A long metal braid also allowed the player to create limited percussive sounds. What it lacked in portability, it made up for in breadth of expression, with its many filters allowing for a wide variety of sounds; listen carefully, and you’ll hear its deep, wobbling tones in recordings by Blood Sweat and Tears and Kal Winding.

Perrey’s first LP, Prelude au Sommeil, was self-released and followed a stint with the (then massive) singer Charles Trenet. Intended for use in mental hospitals to calm agitated patients, it’s a collection of stately lullabies. The pace is glacial, and the effect is too – huge organ chords that drift like icebergs, catching and refracting the dawn light. Heart-shatteringly lovely, and surely one of the first ever chill-out albums.

See also:

Raymond Scott – Soothing Sounds For Baby (Epic, 1962)

Somnolent loop pieces to calm testy bairns, and a fascinating dry run for Scott’s avant la lettre sequencer, the Electronium.

Delia Derbyshire – The Dreams (radio broadcast, 1964)

Freudian fun from the Radiophonic Workshop, with interviewees recollecting night terrors (“I felt as if I was falling forever”) over swampy tape drones.

Jean-Jacques Perrey – Mister Ondioline (Pacific, 1960)

Forgive the deeply terrifying front cover and ever-so-eggy jauntiness – this France-only EP is an important example of early multitracked electronics.

Beaver & Krause

The Nonesuch Guide To Electronic Music

(Nonesuch, 1968)

If there’s any indicator of the strange cultural position the electronic album occupied in the late 1960s – somewhere between harbinger of the future and novelty turn – it’s The Nonesuch Guide To Electronic Music: an audio manual for the Moog that somehow snuck into the Billboard Top 100 and stayed there for 26 weeks.

As a teenager, the Detroit-born Bernie Krause was a session guitarist for Motown, and played with folk outfit The Weavers. Ohio’s Paul Beaver, meanwhile, was an important early proponent of the the synthesized film score, working on soundtracks for The Munsters and My Favourite Martian. A Scientologist and noted eccentric, he played on records by The Monkees and The Byrds, and set up the Moog patch heard on The Doors’ ‘Strange Days’. The two crossed paths at Oakland’s Mills College, where they established themselves as busy Moog-players-for-hire.

The Nonesuch Guide… is essentially a whistlestop tour of the Moog Series II Synthesizer – an attempt to test and document its various functions. The Moog didn’t have a manual at this stage, so Beaver and Krause were proper journeymen, exploring the instruments’ limits and capabilities. It contains 68 short tracks over four sides – a menagerie of bleeps, wibbles, glides and FX. The record’s also bookended by a stunning original composition, ‘Peace Three’, which is only a kickdrum away from sounding like something on Apollo circa 1992.

Before Beaver’s death in 1974, the pair released a string of albums for Warner – bucolic 1970 LP In A Wild Sanctuary, 1971’s comparatively mystic Gandharva and 1972’s All Good Men. Like Cabaret Voltaire’s Chris Watson, Krause now dedicates himself to recording the sounds of the natural world.

See also:

Dick Hyman – Moog – The Electric Eclectics Of Dick Hyman (Command, 1969)

Over a run of albums for Moog, Hyman aimed to “humanize’ and “humorize” electronic music, and these slap-happy compositions tend to tilt towards the latter. Larry Heard enthusiasts will doubly dig ‘The Minotaur’.

Wendy Carlos – Switched-On Bach (Columbia Masterworks, 1968)

The indisputable Daddy of novelty Moog records, initially released as Walter Carlos prior to sexual reassignment at the turn of the decade. A major unit-shifter, and a three-time winner at the 1968 Grammy Awards.

A million-and-one novelty Moog records

Cf. Marty Gold’s Moog Plays The Beatles, Martin Denny’s Exotic Moog, Rick Powell’s Switched-on Country – and, courtesy of The Zeet Band, the immortal Moogie Woogie.

Otto Luening & Vladimir Ussachevsky

Tape Recorder Music

(Gene Bruck Enterprises Inc., 1955)

Holland had its Philips boffins, the musique concrète crew were clustered around Paris’ GRM, Stockhausen held court at his Electronic Music Studio in Cologne – and American electronic music’s founding home was the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Centre. Established by composers Milton Babbitt, Vladimir Ussachevsky and Otto Luening in Manhattan, the studio was the largest of its kind anywhere in the world – a grant-funded playpen dedicated solely to the potentials of electronically generated music, with the Brobdingnagian RCA Mark II synthesizer as its central jewel.

Ussachevsky was a very early adopter of the tape recorder as musical tool, producing tape works throughout the 1950s. Tape Recorder Music presents a 1952 recording at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, performed with Luening some years before the Music Centre came into being. In contrast to many concrète works of the period, there’s a charming melodic sensibility throughout: the pulsing flute tones of ‘Fantasy In Space’ still sound gorgeous, and the ambient ‘Invention In Twelve Notes’ is instantly transportive. It’s mind-boggling that this music is over 60 years old; Finders Keepers sub-label Cacaphonic have, with typical care and flair, since reissued it.

See also:

Karlheinz Stockhausen – Kontakte (Fratelli Fabbri Editori, 1969)

Not an album per se, but sits alongside Varèse’s ‘Poème Électronique’ as one of the most impactful and invigorating electronic recordings of its time.

Vladimir Ussachevsky – Film Music (New World Records, 1990)

Collection of two of Ussachevsky’s 1960s film scores: 1962’s No Exit and 1968’s Line Of Apogee.

Desmond Leslie – Music Of The Future (Musique Concrete, 1960)

Excellent late-1950s concrète experimenter. Once punched Bernard Levin on primetime TV.

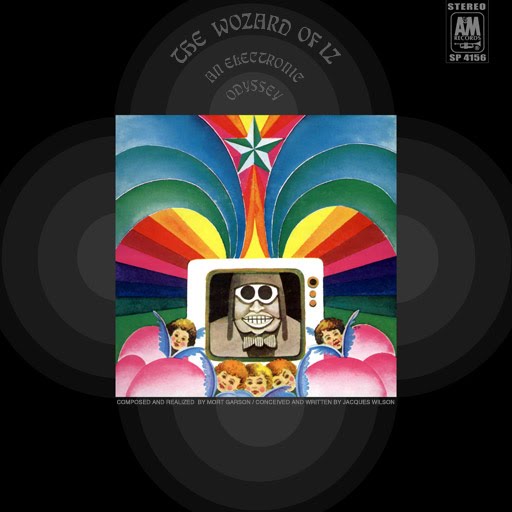

The Wozard of Iz

An Electronic Odyssey

(A&M, 1968)

West Coast Moog dude Mort Garson was another classical-to-electronics émigré: he studied at the Juilliard and earned his stripes in the 1950s as a session musician and arranger (collaborators included that great master of envelope-pushing electronics, Cliff Richard). His grandest achievement was 1967’s The Zodiac: Cosmic Sounds, an important early Moog-meets-rock release for Elektra with contributions from Paul Beaver. Daft as a polka-dotted brush, the album is a conceptual suite centred around the 12 astrological signs – which, amidst psychedelic rock chaff and ponderous spoken word, features some worthwhile electronic interludes.

More fun, however, is the following year’s An Electronic Odyssey – a high-camp retelling of The Wizard Of Oz, credited to The Wozard Of Iz. Dorothy is presented as a pie-eyed peacenik on a journey through the technicolour world of the 1960s counterculture. Highlights include strobing proto-techno cut ‘Leave The Driving To Us’; ‘Never Follow The Yellow-Green Road”s cyborg chorus line; and the eerie soundscape work on ‘Man With The Word’. Top bad trip business, well-suited to Bernard Szajner fans.

More releases would follow in the 1970s, including the brilliant Black Mass – which trades the kookiness of his earlier works for something darker and stranger – and the bottled porno of Music For Sensuous Lovers, released as Z.

See also:

Emil Richards – Stones (UNI Records, 1967)

Probably the first rock album to feature a Moog, with added input from – you guessed it – Paul Beaver.

Bruce Haack – The Way-Out Record For Children (Dimension 5, 1968)

Haack’s masterpiece, The Electric Lucifer, wouldn’t arrive until 1970, but this frazzled album for nippers combines electronic experimentation and whimsy to great effect.

Mort Garson – Electronic Hair Pieces (A&M, 1969)

If wig-out wankery isn’t your thing, Garson’s Electronic Hair Pieces – which features pretty electronic covers of songs from the musical Hair – displays a lightness of touch that lifts it out of the novelty ghetto.

Charles Wuorinen

Time’s Encomium

(Nonesuch, 1969)

Charles Wuorinen – a disciple of Babbitt and Schoenberg – was one of numerous young artists to pass through the doors of the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, and, in the process, tinker with the RCA Mark II Synthesizer – or, as it was colloquially known, “Victor”. Although the Mark II’s capabilities are the stuff of legend – the story goes that Stravinsky, upon hearing about the instrument’s faculties, got so excited he suffered a heart attack – the actual compositions produced on the album were fairly limited. Wonderful works exist – see Babbit’s man vs. machine piece ‘Philomel’ (1964) – but Time’s Encomium is the release that shows Victor in full, impossible flight.

Time’s Encomium is a milestone album: it won Wuorinen a Pulitzer Prize in 1970, making him the youngest ever recipient of the honour. Recorded on four channels and rooted in serialism, it’s a two-part demonstration of the instrument’s muscle. The 15-minute first half starts gently, all wheezes and whistles, with prickly synth tones tentatively circling each other like leery cats in an alley. The second half has a faster metabolism, full of antsy note runs and tone clusters. Heavily processed using analogue studio techniques, it’s a highly expressive work, with remarkable poise and grace for something that was wrestled out of this.

Wuorinen’s subsequent output has been wide-ranging – an opera version of Brokeback Mountain, some essential percussion compositions (notably 1976’s Percussion Symphony) Time’s Encomium, meanwhile, was later remastered and reissued by John Zorn’s Tzadik imprint.

See also:

Richard Maxfield – Electronic Music (Advance Recordings, 1969)

A key figure in the Fluxus movement, Maxfield produced stark works using electronics and tape. Noise scrimmage ‘Pastoral Symphony’ in particular punches hard.

Andrew Rudin – Tragoedia (Nonesuch, 1968)

Flitting, wittering electronics of some repute. Also on Nonesuch.

Folke Rabe

Was??

(WERGO, 1970) [rec. 1967]

Speaking to The Wire back in 2001, Swedish composer Folke Rabe reminded readers that minimal music could be “an enormously sensual experience”, and that rings true in Was?? – a synthesized drone album that makes you feel like you’re sinking into quicksand.

Rabe was an associate of some of the most important figures of the period, including Terry Riley, Pauline Oliveros and La Monte Young. Recorded at the Swedish Radio studios in Stockholm in 1967, Was?? is constructed from layered harmonic sounds, largely made up from electronically generated tones. Rabe has described his methodology as an attempt to “hear into” the sounds, much as a physio might advise a stiff patient to breathe into an intractable muscle. Similarly, Was?? encourages the listener to become attentive to infinitesimal changes in pitch, to respond to the gentlest of inflections; when listening closely, these quiet drones becomes the setting for high drama.

Phill Niblock’s works for trombone are decent points of comparison, but there’s something particularly compelling about Rabe’s rejection of acoustic instruments – a monolithic quality, a sense that these sounds won’t rust or dissipate, but will glower on indefinitely. Trilbies off to Important Records, who put out an excellent reissue last year.

See also:

Rune Lindblad – Death Of The Moon And Other Early Work (Pogus, 1989)

Another key Swede, whose diverse 1950s compositions for tapes and instrumentation are collected here.

Salvatore Martirano – L’s GA – Ballad – Octet (Polydor, 1968)

Notable for the noisy, nasty ‘L’s GA for Gassed-Masked Politico,Helium Bomb,and Two Channel Tape’, featuring a narrator reading lines into a gas mask being pumped with helium. Like Was??, this is extreme music, albeit of a very different sort.

Attilio Mineo

Man In Space With Sound

(World’s Fair Record, 1962)

Many electronic music milestones took place at technology fairs – the sort of places where the curious could goggle at outlandish inventions and state-of-the-art fripperies. The Novachord was unveiled at the New York World’s Fair in 1924; the famous Brussels World’s Fair in 1958, meanwhile, gave Edgard Varèse’s earth-shaking ‘Poème Électronique’ to the world.

Art Mineo’s Man In Space With Sounds was designed specifically for the Seattle World’s Fair in 1962, where it soundtracked the Bubbleator ride. The Bubbleator was a colossal hydraulic elevator in the shape of a bubble, encased in transparent acrylic glass. Once inside, the surface of the glass would appear to warp and blur, giving the impression of seeing the world through a rainbow-coloured lens. Hawked as a souvenir from the exhibition, Man In Space With Sounds is wonderful document of early 1960s futurism.

For the occasional kitschy voiceover moment, a lot of this music is deeply eerie (and, in the case of ‘Mile-a-Minute’, punishingly discordant). Anyone touched or shaken by Mica Levi’s stunning Under The Skin OST will be similarly affected by opener ‘Welcome To Tomorrow’. It’s elevator music, Jim, but not as we know it.

See also:

Harry Revel & Leslie Baxter & Dr. Samuel J. Hoffman – Music Out Of The Moon (Capitol, 1947)

Hugely popular early Theremin album. Fun fact: Neil Armstrong took a copy with him on the Apollo 11 mission.

Paul Tanner – Music For Heavenly Bodies (unofficial release, 1958)

Heavily orchestrated album for electro-Theremin. If chipper exotica is your bag…

Dean Elliott – Zounds! What Sounds! (Capitol, 1962)

Razzle-dazzle big band music, with a liberal smattering of manipulated found sound. Promises “celery stalks (the crunchiest), 1001 clocks, bowling pins and many, many more!!”

Morton Subotnick

Silver Apples of the Moon

(Nonesuch, 1967)

Morton Subotnick, like Terry Riley, Pauline Oliveros, Steve Reich and others, attended Oakland’s Mills College – essentially a finishing school for 20th century musical vanguardists. Alongside Ramon Sender, he set up the San Francisco Tape Music Center in 1962 – a hipper, more playful alternative to, say, the Columbia-Princeton lab. Subotnick worked across a range of media, putting on immersive theatre events and light shows and collaborating extensively with club/happening Electric Circus.

Silver Apples of the Moon is a significant work – the first extended piece of electronic music directly commissioned by a major label. Written to a 13-month deadline, it was recorded in 1966-7 at NYU on a portable Buchla 100 synth – an instrument Subotnick and the Tape Music Center had helped develop. It’s also essentially the first large-scale ‘classical’ composition premiered not with a performance, but with a physical release – a significant shift of gravity away from a culture of performance towards a culture of playback.

Tailored to fit onto the two sides of a 12″, the results are an involving set of fizz-bang electronics. The first half is strange and mischievous: pinprick tones strafe around the stereo field, and gentle passages are suddenly interrupted by conniptions of electronic noise. The flip is much more forward, based around sequenced synth phrases – still an innovation at the time – over which Subotnick splatters beeps, bleeps and trance stabs with all the finesse of a toddler with a foam hose. Subotnick’s later works – 1970’s Touch and 1971’s Sidewinder in particular – would be more considered, but Silver Apples of the Moon is the one that booted the door in.

See also:

Various Artists – Electronic Music (Turnabout, 1966)

First in a commendably adventurous compilation series from classical label Turnabout, featuring material from Ihran Mimaroglu, Andres Lewin-Richter, Tzvi Avni, and Wendy (then Walter) Carlos.

Pauline Oliveros – Reverberations: Tape & Electronic Music 1961-1970 (Important, 2012)

Oliveros’ 1960s LP output is basically non-existent, so Important’s sprawling 12xLP box set is an essential insight into her earliest work.

Louis & Bebe Barron

Forbidden Planet

(Small Planet Records, 1976) [cinema release, 1956]

Forbidden Planet didn’t get an official release during the 1950s – or, indeed, the 1960s – but it’d be churlish not to include the first entirely synthesized commercial film score – and doubly snitty to ignore a work of this quality.

Married couple Louis and Bebe Barron began experimenting with tape manipulation in the 1950s; the story goes that the couple were given a tape recorder and magnetic tape – rare luxuries at the time – as wedding presents. Unlike some of the other lab-coated academes in these pages, they were fully engaged in the counterculture: recording audiobooks with Anaïs Nin, hanging out in Greenwich Village, and working on tape music projects with John Cage, David Tudor, Christian Wolff and others (see their exhaustive/exhausting Williams Mix).

The Barrons secured the Forbidden Plant commission after gatecrashing a party held by the President of MGM and strongarming him into hearing their work. Electronic FX weren’t new, of course – a raft of B-movies or classics like The Day The Earth Stood Still had flirted with the medium – but Forbidden Planet marked a sea (devil) change. Working with oscillators, the Barrons overloaded circuits to try and create new sounds, and experimented with pitch shifting and tape reverse to make odd sounds even odder. Louis built the circuits, while Bebe arranged and organised the results. The OST still chills – a riot of blasts and whooshes, lowing machinery, and enough tremolo to induce labour. Sadly, they’d never had same sort of multiplex commission again.

See also:

The BBC Radiophonic Workshop – BBC Radiophonic Music (BBC, 1968)

Because this.

Louise Huebner – Seduction Through Witchcraft (Warner Bros, 1969)

Occult soliloquies, backed by composition by the Barrons, and inexplicably released on a major label. File with The Flowers of Evil.

Tod Dockstader

Quatermass

(Owl Recordings, 1966)

Many of the artists discussed were constellated around academic hubs or technical labs; in that context, Dockstader was a lone wolf. The Minnesota native started out producing sound for animated films (remember Gerald McBoing-Boing?), then put in time as a sound engineer at Gotham Recording, composing onto magnetic tape. His was a film effects background – one of results rather than high theory, of spirited amateurism rather than clinical process.

Dockstader produced a number of records of “organised sound” in the 1960s: essentials include the coruscating, otherworldly Water Music, and the striking Eight Electronic Pieces. His finest work, though, is 1964’s Quatermass, released on nature recordings label Owl Records. Split into five parts, the 45 minute composition was designed by Dockstader to be “dense, massive, even threatening.” Working for the first time with a three-track tape recorder, Dockstader was able to layer and counterpoint his source material more intricately than ever before. Pulled from a huge library of of source recordings – 300,000 feet of tape’s worth, according to Dockstader – Quatermass is saturnine and occasionally aggressive, with the sort of scope that only Parmegiani’s later De Natura Sonorom would really touch.

See also:

Kenneth Gaburo – Music For Voices, Instruments & Electronic Sounds (Nonesuch, 1968)

Gaburo’s work veered all over the shop, and this fine selection of tape works showed he could stand toe-to-toe with Stockhausen when required.

John Pfeiffer

Electronomusic: 9 Images

(RCA Victrola, 1968)

An engineer and producer first, Pfeiffer made his name with comprehensive reissues of work by classical composers like Rachmaninoff and Toscanini. Behind the scenes, he helped implement new stereo, quadraphonic and digital recording techniques for RCA. Electronomusic is his own step into the (admittedly fairly dim) limelight – a self-described “head-in-the-stars-feet-on-the-ground” affair.

Electronomusic is conceived as an attempt at reconciling the wild possibilities of electronic composition with a sense of clear musical purpose. There are some traces of Pierre Schaeffer – ‘After Hours’ layers rattling typewriters and ringing phones into a stern industrial collage – but for the most part, these pieces feel abstract and synthetic. The nine tracks are pitched as “attempts to conjure up images”, and these pieces have a bold, synaesthetic quality: attend to the stippled chimes on ‘Warm-Up, Canon And Peace’; the fluoro loop-di-loops on ‘Drops’; the multicoloured dust-clouds billowing through ‘Take Off’; and, best of all, ‘Forests’, which sounds like it could have been plucked straight off of one of Alva Noto and Ryuichi Sakamoto’s mid-2000s collaborative LPs.

See also:

Daphne Oram – Listen, Move And Dance Vol. 1 (His Master’s Voice, 1962)

These drip-drop pieces for infants from the Radiophonic Workshop legend – released sans vocals as the Electronic Sound Patterns EP – still transfix and delight.

Pietro Grossi – Electronic Soundtracks (Cooper, 1966)

Cellist-turned-computer musician Grossi released a clutch of albums in the 1960s and 1970s, and the first – a cerebral, carefully organised, algorithmic affair – explores similar terrain to Pfeiffer.

John Cage & David Tudor

Indeterminacy: New Aspect Of Form In Instrumental And Electronic Music

(Folkways, 1959)

John Cage and David Tudor are both mammoth figures in the development of electronic music: the former for his tape pieces and theoretical insight, the latter for his transition from virtuoso pianist to committed electronic producer and instrument builder. Their collaborations are legion, and Indeterminacy – recorded and released on Folkways in 1959 – is one of the most iconic.

The performance sees Cage read 90 randomly assembled stores, each one lasting one minute, whilst Tudor tinkers with piano and tape in a separate room. Neither performer can hear each other, creating an aleatoric performance in which the two artists become unwitting collaborators. Correspondences or moments of discordance are entirely accidental. Indeterminacy enters our ambit on account of Tudor’s tape manipulations, which use Cage’s 1958 production Fontana Mix as a jump-off point. The results make for a stunning collision of man and machine, the organised and the random.

The piece has had a number of curious afterlives, including a recent run of performances by Stewart Lee. The least authentically “electronic” record on this list, for sure, but one that reflects the diversity of approaches to synthetic or manipulated sound, and an essential point of entry for people new to either party.