Like this? Check out FACT’s rundowns of the 100 Best Albums of the 1990s and the 100 Best Albums of the 1980s.

“Ah”, said a wise old former FACT staffer about this list, “possibly the best decade of them all?”

Looking at the evidence, it’s hard to argue: this is the decade that brought us fusion’s high noon, ten summers of disco, the rise of the dub cosmonauts, ambient’s first stirrings, and the viperous bite of punk. Electronic music left the academies and the novelty charts and started to infect rock and pop wholesale. Prog gazed upwards, New Age looked inwards, metal plumbed the depths – and the Germans released a lot of great records.

More than anything, though, this was popular music’s Cambrian period: a melting pot from which vital new forms (hip-hop, house, post-punk) would already be emerging by the end of the decade. It’s a decade of strange combinations, of unlikely correspondences and (to reference one album on the rundown) chance meetings – some disastrous, some very auspicious indeed.

As with previous lists, we’ve sought to represent the period in all its diversity. As ever, this is not some hoary retelling of The Canon™, nor is it a beardier-than-thou list for contrarians and Discogs gollums. Rather, these are 100 records we simply couldn’t live without – records that have shaped our collections, our favourite artists’ collections and, in ways big and small, the development of popular music in the late 20th century.

We’ll be counting down the list all this week – twenty per day, finishing up on Friday.

To accompany the list, our team have curated and recorded five mixes, featuring material from all the records on the rundown. We’ll be unveiling these day-by-day in tandem with the list:

100. Anna Lockwood

The Glass World of Anna Lockwood

(Tangent, 1970)

Amongst a particular cadre of experimental musicians and field recordists, Anna – or, as she was subsequently credited, Annea – Lockwood’s glass concerts of the late 1960s and early 1970s are the stuff of legend. Installed in dark rooms with a modest light display in tow, the New Zealander rubbed and struck an array of different glass vessels (bottles, jars, tubes) and panels, extracting coos and yelps from these inanimate objects – a sort of double-glazed siren song. The Glass World of Anna Lockwood presents compositions in a similar vein: the results are gorgeous and otherworldly, and herald a decade characterised by curiosity and miscegenation. Not sure what she’d make of Justice Yeldham, though.

99. Libra

Schock

(Cinevox, 1977)

Goblin might (quite rightly) get most of the attention when the conversation zeroes in on Italian horror soundtracks, but there are plenty more gems out there if you care to take a closer look. Libra’s proggy accompaniment to Mario Bava’s Schock is one of the best of ‘em, and it probably won’t come as a surprise to hear that the band were actually only a degree of separation away from Goblin. Drummer Walter Martino had performed with the Italian horror heavyweights in 1975, and while he’s uncredited on the album’s liner notes, long-standing Goblin keyboardist Maurizio Guarani actually drops a few of his signature stabs too.

While Bava undoubtedly wanted to repeat Dario Argento’s winning formula, tracks such as the discordant ‘La Cantina’ might be even more eerie than anything you’d find bothering the Profondo Rosso OST. In fact, it’s those peculiar avant-garde synth touches that give Schock such a unique set of fingerprints, and with gorgeous, spooked-up tracks like ‘L’Incubo’ and ‘Transfert IV’, it’s well worthy of re-appraisal.

Spencer Hickman (Death Waltz Recordings): “Perfect companion piece to Suspiria, with Libra not surprisingly sharing member Maurizio Guarini. Huge , overly pompous prog rock littered with scattershot synth effects , disco flourishes and absolutely mental breakdowns which give way to almost folksy ambient segments – this record sums up all of the excesses of the italian giallio genre and is all the better for it. You don’t just listen to this record you experience it”

Spencer Hickman (Death Waltz Recordings): “Perfect companion piece to Suspiria, with Libra not surprisingly sharing member Maurizio Guarini. Huge , overly pompous prog rock littered with scattershot synth effects , disco flourishes and absolutely mental breakdowns which give way to almost folksy ambient segments – this record sums up all of the excesses of the italian giallio genre and is all the better for it. You don’t just listen to this record you experience it”

98. Gary Wilson

You Think You Really Know Me

(MCM, 1977)

Prime contender for the Least Appropriate Babymaker on this list, You Think You Really Know Me is a bug-eyed collection of traumatised kitsch and spooky boogie-woogie. Inspired by a childhood meeting with John Cage, this New York outcast set out to become “a teen idol in front of a Cage performance, singing love songs but being avant-garde.” Wilson’s sad-sack persona is the main draw, but the compositions (the twitchy ‘When You Walk Into My Dreams’; apocalyptic sex jam ‘6.4 = Makeout’) have serious clout too. Now recognised as an outsider pop classic, it still creeps and thrills – a blue-eyed soul album made by a water-damaged droid.

97. Can

Ege Bamyasi

(United Artist Records, 1972)

Forget worthies like Stephen Malkmus and Thurston Moore and Beck and Kanye West giving their regal nods to this album – it doesn’t need any of them. All you need to know its greatness is to see a halfway decent DJ drop ‘Vitamin C’ in a club, and see how gloriously the groove abides. That one moment is enough to realise that krautrock is not about collectors and catalogues and worthiness: as much as anything it’s about the primacy of the present moment and the cavorting foolishness of funk. Ege Bamyasi isn’t afraid to get dark – nightmarish, even, in the second half of the ten minute ‘Soup’ – but when Jaki Liebzeit gets rolling and everything else locks into step with him, Can are every inch the multidimensional interstellar groove machine that Parliament/Funkadelic, for example, ever were.

96. Talking Heads

Fear Of Music

(Sire, 1979)

77 and More Songs About Buildings and Food are great – really, really great in parts, and well ahead of the curve – but listening back now, they were too easily imitable, and seem a little of a part with the US new wave that followed. Fear of Music, though, is the one where the band left all the others around them behind, and become completely Talking Heads, impossible to copy despite all the attempts that continue to this day. And from this through until True Stories in 1986, taking in five studio and two live albums, they never put a single foot wrong. So there’s definitely an extra retrospective frisson in knowing exactly what wonders this was the beginning of, the thrill of a band standing on the threshold of true greatness – but even taken on its own merits it’s an absolute marvel. It’s got a heart of ice, the hot guts of funk, and a brain full of bats and butterflies. What else could you need?

95. Captain Beefheart & The Magic Band

Lick My Decals Off, Baby

(Straight, 1970)

Okay, so Trout Mask Replica might be the established pick when it comes to Beefheart’s “classic” run, but those with an open mind and a keen ear might notice that its follow-up Lick My Decals Off, Baby (which came only a year later, in 1970), while notably less batshit eccentric, might be even more successful. It’s certainly more succinct, and ditches some of its predecessor’s boss-eyed indulgence, instead hitting on a seam of radio-length, jagged experimental pop.

Tight and inventively produced, Don Van Vliet had more autonomy over these recordings than ever before, and it shows. Zappa’s influence was certainly still present, but with Van Vliet at the helm there’s a coherence here that was never again matched. It’s hard to believe that the bizarre collection of songs actually nicked the UK top 20, but that’s what two thumbs up from John Peel would do.

94. Bruce Haack

The Electric Lucifer

(Columbia, 1970)

On the evidence of The Electric Lucifer, Bruce Haack might reasonably be called early electronic music’s William Blake – a marginalised, self-publishing savant making gnomic work about the grand metaphysical tussle between good and evil. Using home-built synthesisers and vocoders, Haack follows his loopy run of children’s albums with this deep-fried collection of synthesised acid rock. With one foot in the novelty Moog records of the late 1960s, Haack tilts between Biblical cant, psychedelic pop, robo-ballads, and whirlers-gone-wrong bleep fare. Nutty as anything, but, in its own shoddy way, years ahead of its time.

93. Charlemagne Palestine

Strumming Music

(Shandar, 1974)

Like Terry Riley, Steve Reich and Phill Niblock, Charlemagne Palestine dines at minimalism’s high (and, presumably, Bjursta) table. Performed on a Bösendorfer grand piano with the sustain pedal depressed, this 52-minute recording sees Palestine hammering out gradually shifting note patterns. Like some holy trick of the light, overtones gradually accrue, meld and blur, creating a great shimmering nimbus of sound. Strumming Music has real physical heft – it’s essentially Palestine whacking seven shades out of a piano for an hour – but the result is spectral and gorgeous. In contrast with his eccentric presentational approach (he performs in garish outfits, surrounded by stuffed toys) Strumming Music is pure as driven snow – piano strings braided into a rope to heaven.

92. Devo

Q. Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!

(Warner Bros, 1978)

Of all the sideways-thinking iconoclasts clearing the rubble after punk’s big bang, Devo were perhaps the least comprehensible, and most apparently sui generis of them all. A pop group wrapped in a surrealist art troupe inside a gang of synth-wielding, terraced headgear-sporting maniac philosophers from Akron, Ohio (of all places), the five-piece offered a blunt rejection of the previous decade’s tired rock and roll cliches on their debut album, an idiotically catchy collection of stilted rhythms, barked vocals and childlike imagery that roundly rejected the slop and mess of guitar rawk (a tactic that reaches its acme on their gloriously bananas, totally de-sexed redo of the Stones’ ‘(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction’). Thoroughly postmodern in their mingling of highbrow satire and lowbrow artifice, it’s little wonder Brian Eno elbowed his way to the front of the queue to act as producer on Q: Are We Not Men?.

91. Bridget St. John

Thank You For…

(Dandelion, 1972)

One of the lovelier dispatches from the tail-end of the late 1960s British folk explosion, Bridget St. John’s third solo album – released on John Peel’s Dandelion imprint – is all honey, dog-rose and optimism. Less plugged into the traditional English folk idiom than other landmark albums from the period (Sandy Denny’s Denny, Silly Sisters’ 1976 LP), these are pretty songs stunningly performed, with some surprisingly opulent production touches – less Birnam Wood, more Lee Hazlewood. The lovelier moments (‘Happy Day’, the title track) show that, even with the Summer Of Love long departed, the winsome optimism of the 1960s was still quietly intact.

90. Ghédalia Tazartès

Diasporas

(Cobalt, 1979)

French outsider artist Tarzatés doesn’t just operate in a field of one – he’s the solitary occupant of his own continent, one where marshland fringes jungle and the weather changes on a dime. His 1979 debut sounds like nothing else – a thrilling collection of meanie devotionals, snafu song and fevered goatherd music. Stitched together from tape loops, Diasporas is a babel of spoken word, industrial grind, musique concrète and throat singing, topped off by Tarzatès distinctive/distressing heckled-by-a-goblin vocal delivery. Faint-hearted? Best give this one a miss, fraidy-cat.

89. Curtis Mayfield

Curtis / Live!

(Curtom, 1972)

Did anyone in the seventies have a run of albums to match Curtis’? Including soundtracks, he made EIGHTEEN in the decade – all good, all self-produced – and really, out of those, any of Curtis, Superfly, Curtis in Chicago, Sweet Exorcist or There’s No Place Like America Today are easily deserving in a place of this list. You could argue for years about which is better, but what you can’t argue against is the absolute joy of this one. The live recording is pristine and shows all the fine detail of the band’s intricate chamber funk just so. The social conscience, the wry humour, the superfly swagger, the extraordinary gentleness and nobility of Curtis’s approach are all displayed to their very best advantage, and more to the point it sounds like a laid-back but swinging party you’re very happy to be invited to.

88. Magma

Köhntarkösz

(A&M, 1974)

Magma’s output is punk Kryptonite – prog largesse at its most self-serious, complete with Hubbardian mythology, invented languages, and enough choirs to fill Carmarthenshire twice over. It’s also, obviously, often as brilliant as it is unwieldy, and nowhere more so than on the French outfit’s fifth studio LP Köhntarkösz. Less consciously ker-ker-krazy than 1973’s Mëkanïk Dëstruktïẁ Kömmandöh, Köhntarkösz is a triumph of pomp and pyro, sometimes hushed and sinister (the title suite’s opening moments), sometimes jagged and abrasive (‘Ork Alarm’), and off its rocker from end to end. Zeuhl lives!

87. Robbie Basho

Visions of the Country

(Windham Hill Records, 1978)

Quavering troubleman music sung straight from the gut. Part of the same axis as John Fahey and Leo Kottke, Basho’s whale-throated take on the American blues tradition (with some added Eastern influence to boot) still has the power to shake listeners to the core. Visions of the Country – Basho’s tenth solo LP – strikes a wonderful balance between chops and chutzpah: Basho’s spasmodic fingerpicking is technically brilliant, but his foghorn vocal takes have all the guilelessness and raw feeling of the amateur. Many prefer the quiet mystique of his instrumental albums, but Visions of the Country is disarmingly open-hearted; only the sociopathic or the blockheaded will be able to get through it without goosebumps.

86. Gaz

Gaz

(Salsoul Records, 1978)

Compulsory Salsoul… and this is a very silly record. The Star Wars ‘Cantina Band’ cover tips it over the edge, but everywhere there’s foolishness – the orgasming alien seductress voices in ‘Interstellar Love Affair’, the fact ‘The Force’ sounds like the most preposterous Seventies cop show theme, the fact the sinister tomtom-rolling intro of ‘Indian Gaz’ gives way to voices that spend the rest of the song jauntily going “shoop-shoop-shoop-shoobie-dowahhh”, the title of ‘Synth He Sized Her’, and the fact that everywhere you turn there’s an infernally catchy parping horn riff or a trippily happy little synth gurgle. But that’s the whole point. Only raging bores edit the silliness out of disco – this is shot through with a combination of wide-eyed innocence and drug-mangled wig-outs that still feels very alive. A glorious folly.

85. Harmonia

Deluxe

(Brain, 1975)

Look, for a moment, at the list of personnel we have on Deluxe – apart from the core trio of Dieter Moebius and Hans-Joachim Roedelius (of Cluster) and Neu! axe fondler Michael Rother, legendary German producer Conny Plank is behind the boards, and Guru Guru drummer Mani Neumeier helps out on percussion. It’s hardly surprising, then, that the record is one of the finest to emerge from the krautrock era, and almost four decades later it still sounds unmatched.

Fusing the motorik throb of Neu! and the kosmiche warmth of Cluster was an idea the band only touched upon on their (also excellent) debut Musik von Harmonia. Deluxe was the point where everything just fell into place – a collection of real songs blessed with the depth of then divergently modern soundscapes and ideas that would soon fall into normality.

84. Billy Cobham

Spectrum

(Atlantic, 1973)

Drummer with The Mahavishnu Orchestra and a Miles Davis sideman, Cobham is fusion royalty. Debut solo LP Spectrum was knocked out quickly – 10 days of recording on a minuscule $20,000 budget – but it still sounds hugely assured; where some fusion records are strange, muddled stews, Spectrum brings funk, jazz and rock chops into productive coalition. Unlike The Inner Mountain Flame, say, Spectrum sees Cobham in total service of the groove, with his cephalopod playing carrying the best tracks here: highlights include the car-chase rock’n’roll on ‘Quadrant 4’, and the muscular ‘Stratus’, later plundered for Massive Attack’s ‘Safe From Harm’. And, the gluten intolerant listener will be pleased to hear, there’s barely a noodle in sight. Big seller, too.

83. Kevin Coyne

Marjory Razorblade

(Virgin, 1973)

A sprawling double album of earthy, shattered blues by an enduringly under-the-radar figure, Marjory Razorblade might be imagined as the troubled distant cousin of Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, with Kevin Coyne’s similarly scuffed, nicotine-stained wails directed not at misty memories of days gone by but subjects more firmly rooted to the ground – ‘Eastbourne Ladies’ with powdered faces, lonely ‘Jacky’ mourning his long-gone Edna, and the ‘House On The Hill’ and its forgotten residents, inspired by his own experiences working in psychiatric wards. Almost as essential, yet utterly different, to his solo opus is Babble, a 1979 collaboration with avant-rock icon Dagmar Krause depicting a troubled relationship in intimate, harrowing detail.

82. Crass

Stations of the Crass

(Crass Records, 1979)

Forget Beckham in a Crass t-shirt – what has kept Crass relevant, through dance, metal, skate culture and beyond, isn’t their iconography, good though it is. And it’s not their politics which were, to be charitable, pretty basic. No, it’s the fact that their music is really great. Exactly as punk was supposed to be, it’s completely unschooled but super-tight, transmitted direct from the nervous system, and also as intensely weird as a band with a deep hippie background should be, with smearings of free jazz and tape experimentation.

When they kick up their wiry rhythms, all of the ranting – which taken alone manages to be both sneery and earnest at the same time – becomes less of a lecture and more of a heartfelt outpouring, especially when combined with the more overtly nonsensical stuff like endless repetitions of “YOU’VE GOT BIG HANDS!”. Those rhythms and that shamanic weirdness are why Soft Pink Truth turning anarcho-punk into house worked so well: it was already tripped-out dance music. Together with Hawkwind, who form the opposite pole in the crusty-festy axis, Crass’s music forms a vital current in the British underground and beyond. But records like this stand up on their own, regardless of “significance”.

Mumdance: “I used to listen to this album on rotation when I was younger & heavily into BMX & skateboarding, so it reminds me of a lot of good times every time I hear it. Steve Ignorant has one of the best and most archetypal vocals in punk in my opinion & he shines on this album. I really like how it’s quite shambolic and all over the place, but at the same time fiercely intelligent and experimental in some places. You can hear echoes of this album not only in subsequent punk albums, but further afield too.”

Mumdance: “I used to listen to this album on rotation when I was younger & heavily into BMX & skateboarding, so it reminds me of a lot of good times every time I hear it. Steve Ignorant has one of the best and most archetypal vocals in punk in my opinion & he shines on this album. I really like how it’s quite shambolic and all over the place, but at the same time fiercely intelligent and experimental in some places. You can hear echoes of this album not only in subsequent punk albums, but further afield too.”

81. Jon Lucien

Rashida

(RCA Victor, 1973)

Seventies borderline-mainstream weirdness at its best. According to Jon Lucien himself, “the record company was attempting to package me as a sort of ‘black Sinatra’. Once the white women started to swoon at my performances, their attitudes quickly changed.” Realistically, the Virgin Islands-born American singer was unlikely to ever be a Sinatra, though, thanks mainly to his over-egged “stop all war, let the children be free, man” rhetoric and penchant for massed Brazilian harmonies. The emoting and cheese take a minute to get past on this album, but once you let the Hollywood levels of lavishness in the arrangements wash over you and the omnipresent tropicalia shimmy get into your bones, it’s extraordinarily addictive. Proper silk sheets, big moustache, Seventies playboy seduction music.

80. Sex Pistols

Never Mind The Bollocks, Here’s The Sex Pistols

(Virgin, 1977)

It was bound to happen. In 1977, the rock landscape was liberally spotted with beardy “progressive” explorations of avant jazz, classical music and traditional folk. It was quite normal for a band to belch out a gatefold sleeved concept album blessed with the kind of wretched fantasy artwork that wouldn’t have even looked cool when you still had pale blue Y-fronts in your underwear drawer, and for quite obvious reasons, it had to stop.

Punk was the answer, and whatever you think about Never Mind the Bollocks and its head-on collision of snot, fashion and total disregard for “the system” as it was, 1977 needed it, desperately. The style was, in many ways, more important than the substance, but even now it’s hard to hear ‘Pretty Vacant’ or ‘Bodies’ and not want to chuck a brick through someone’s window. Wizard costumes out, safety pins in.

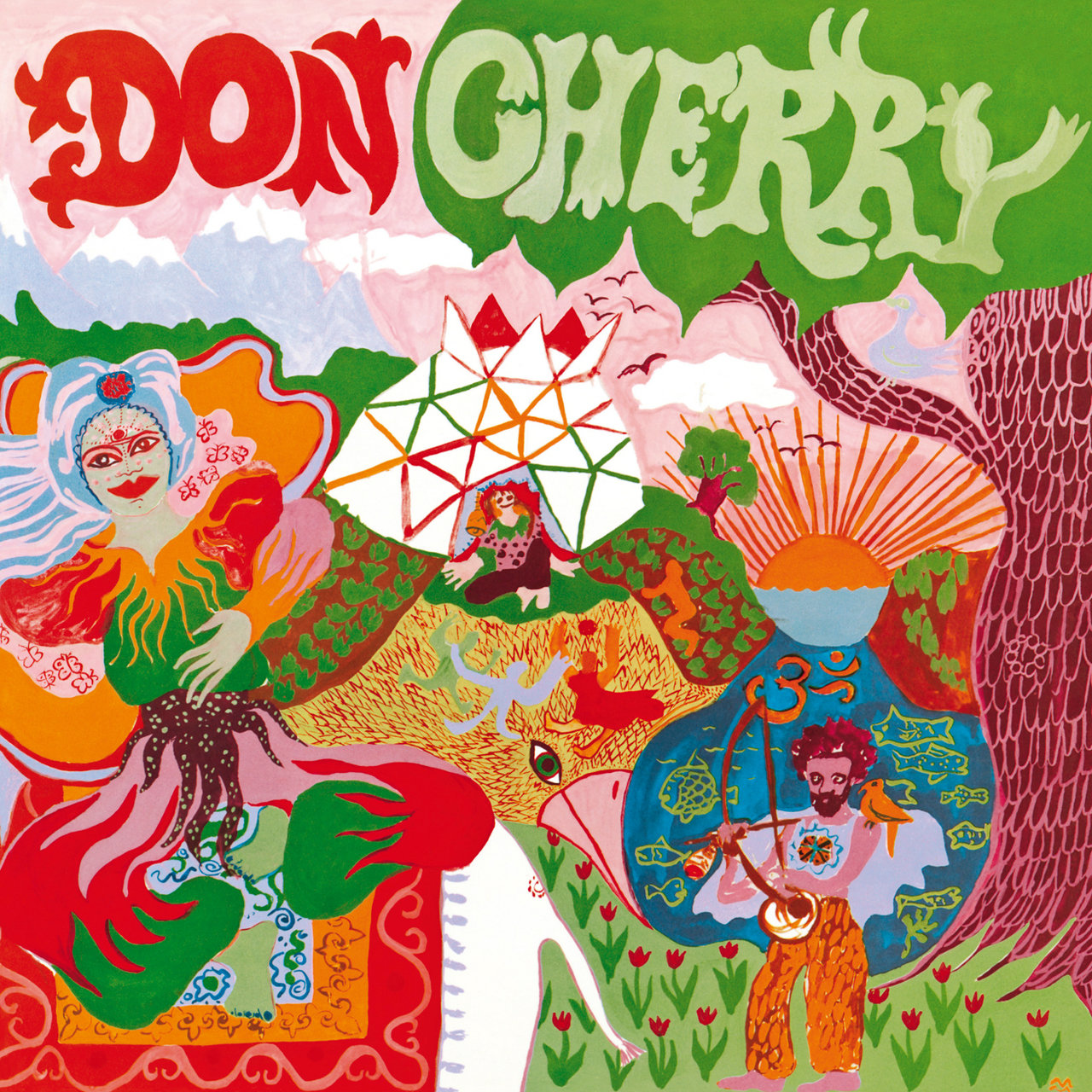

79. Don Cherry

Organic Music Society

(Caprice, 1972)

An ambitious album to say the least, Organic Music Society, as the title suggests, is a scented pot-pourri of sounds drawn from across the globe, created long before anyone concocted the expression “world music”. A large ensemble session, featuring exotic percussion instruments and Afro-Brazilian grooves, it’s a jarring listen – in part due to the way different recordings were fused together by Cherry, drawing from studio jam sessions, one-mic demos and field recordings. Highlights include great versions of Pharoah Sanders’ ‘The Creator Has A Masterplan’, Dollar Brand’s ‘Bra Joe From Kilimanjaro’ and two Terry Riley compositions as well, which should give you a sense of just how heady and pan-continental a cocktail this is. Despite the eccentric sequencing, it remains a powerful and electrifying listen, with Cherry’s trumpet tone ranging from deafening foghorn to folkish whimsy in the same breath.

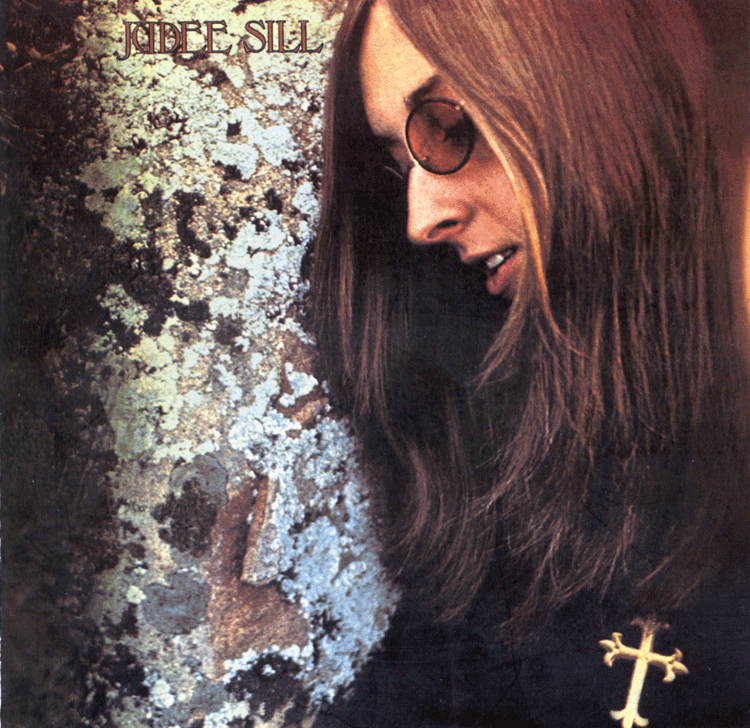

78. Judee Sill

Judee Sill

(Asylum, 1971)

You can turn over a new leaf, but the blots show through. Sill’s backstory – itinerant former heroin addict and, for a time, bank robber – might not initially square up with the sunkissed SoCal rock of her debut album, but her lyrics, full of dark mysticism, cosmic disorder and fire-eyed beasts, make Judee Sill a much more ambiguous – not to mention ambitious – proposition. The lyric sheet might sometimes read like a passion play, but Sill’s not as hectoring as your average pulpiter; there’s more complex, meaningful cosmology packed into ‘Crayon Angel’ than plenty of callow prog acts mustered in their entire careers. Overshadowed on Geffen’s release schedule by two biggies, Jackson Browne and Eagles, it’s now recognised for the achievement it is: a triumph of gimlet-eye arrangements and third eye vision, and breathtakingly gorgeous with it.

Sanae Yamada (Moon Duo): “What I feel when I listen to Judee Sill is what I felt in the small patch of woods behind my childhood home, where I would go to press my hands against the trunks of trees whenever I was upset. It is a sense of primal contact, an inarticulable calming, a window on the mystery. There is an Earth-bound plaintiveness, soulfulness, and utter lack of calculation in her voice that make it seem more like the emanation of an unidentified natural element – a shimmering connective tissue, vibrating somewhere between wood and water, rock and air.”

Sanae Yamada (Moon Duo): “What I feel when I listen to Judee Sill is what I felt in the small patch of woods behind my childhood home, where I would go to press my hands against the trunks of trees whenever I was upset. It is a sense of primal contact, an inarticulable calming, a window on the mystery. There is an Earth-bound plaintiveness, soulfulness, and utter lack of calculation in her voice that make it seem more like the emanation of an unidentified natural element – a shimmering connective tissue, vibrating somewhere between wood and water, rock and air.”

77. Prince Far I

Under Heavy Manners

(Joe Gibbs Music, 1976)

In 1976, Jamaica was in economic and political disarray, with Prime Minister Michael Manley declaring a state of emergency. Cue this LP of socially engaged chanting from one of the great Jamaican deejays, delivered in an orotund baritone that penetrates straight to the foramen magnum. Heavy’s the operative word: mighty bass, serious subject matter and Far I’s million-fags-a-day voice. Under Heavy Manners collects impassioned devotionals (‘You I Love And Not Another’), stern finger-wags (’Young Generation’), and fire’n’brimstone preaching (‘Shadow’), all with a none-too-subtle political streak. Joe Gibbs and Errol Thompson’s swampy production augments the end-is-nigh feel. And is there a better opening three-and-a-half minutes on this list than ‘Rain A Fall’ – Far I’s ode to rumbling bellies and rattling sternums? More weight!

76. Guru Guru

UFO

(Ohr, 1970)

Germany was a hotbed of innovation in the ’70s, and while Guru Guru didn’t have the showy rhythmic smarts of Neu! or the grand axe gestures of Amon Düül II, they had plenty to offer on their noisy, irreverent debut UFO. Compared to some of their peers, their sound was bordering on the inept – crunchy waves of guitar, falling in and out of discernible tune and often covered with a bleak blanket of white noise. It is, however, music that can truly bear up to the description “psychedelic” – the kind of mind-altering material that you can only begin to pick apart after a serious session of self-medication.

75. Bernard Parmegiani

De Natura Sonorum

(INA-GRM, 1976)

The landmark electroacoustic album of the decade, De Natura Sonorom trades the snap cuts and sharp edges of much musique concrète for something much more fluent, beguiling, authored. Working from a vast catalogue of sound sources, De Natura Sonorum is a creole of organic sounds and electronic textures. The tracklisting might read like a PhD appendix (‘Natures Éphémères’, ‘Matières Induites’), and Parmegiani’s process might seem off-puttingly forensic (“I placed the sounds as you do letters, one after the other, so as to create forms and sequences”). But the results – a multi-part symphony, composed from bubbles, balloons and blinking metal boxes – shimmer and beguile. Easily the most out-there record in this rundown, and the one most likely to change the way you listen.

Miles Whitaker (Demdike Stare): “Given the rather heavyweight task of writing about such an ‘academic’ record, never mind such a difficult one, is weighing upon me. So, like my own background, I’ll refute the academic side and keep it simple, and I’ll just tell you why you shouldn’t listen to this record. Basically, you’re not ready for it.

Miles Whitaker (Demdike Stare): “Given the rather heavyweight task of writing about such an ‘academic’ record, never mind such a difficult one, is weighing upon me. So, like my own background, I’ll refute the academic side and keep it simple, and I’ll just tell you why you shouldn’t listen to this record. Basically, you’re not ready for it.

“Ten years ago when I first heard it, I wasn’t ready. I said so at the time, it made no sense; I hadn’t immersed myself enough in the whole spectrum of music enough to understand it, nor did I pay any heed to the context of the record, musical theory or musical evolution for that matter. I hadn’t yet taken the steps that helped make sense of it, sonically, not academically. SoIi left it alone.

“Fast forward to 2012, when my partner in music, Sean Canty, who has done so much to drag me out of the gutters of music, into the world of sonic wonder, forced me to buy an original copy of it, he told me I was ready. He was right, I was ready to hear it, finally, but I wasn’t ready for the feeling of inadequacy that it brought.

“Without fear of upsetting, or cheapening, a lot of musicians working today and in the past, there are more amazing sounds in this one record than in most people’s careers. I mean that wholeheartedly, and sincerely, and I also include myself in that statement. I’ll also state, this is probably the best recorded, excruciatingly exact record you will ever hear in your life.

“There are lots of words bandied around when people are writing or describing music or musicians, especially new music, and those words are now thrift store descriptions, normalised to the point of uselessness, they carry no more weight than normal descriptive terminology. Such terms as genius, amazing, experimental, next-level, astonishing, are all used week in week out to hype, or illuminate another new record or artist. Well, I apologise for most of those reviews, and to the reviewers who’ve used these terms, (and the artists on the receiving end) but those kind of descriptions should be reserved for the very few artists who deserve the actual term artist. Someone who propels their craft far beyond the boundaries most of us never test. To simplify, I’ll steal a line from a comedian I heard in Berlin, talking about Berlin, (though I’m sure it’s been said before elsewhere), “So many artists, so little art”.

“Well, when you hear De Natura Sonorum in the right context, at the right time, it makes everyone else seem fake. Rightfully so, because it is a work of utter genius. I remember phoning Sean the week I digested De Natura Sonorum, all I could say was that it made half of my record collection redundant, there was no going back in some ways.

“There are so many astonishing noises, that you’ve NEVER heard in your life, until you hear Parmegiani. The sounds and execution are alien, in the very sense of the word, it is the best outsider music there ever will be. Every moment is crafted, in the real sense, cut, edited and placed just so. The pieces are sculpted to the nth degree, yet contain so much art and content as to make me feel completely inadequate as a music producer. In some ways, I wish I’d never heard Monsieur Parmegiani, though of course my life is richer for it.

“I hold it as one of the most special records I’ve ever heard, as it has been made by a true master of the craft. Though you shouldn’t take my word for it, remember it won’t make sense, because you’re not ready for it.”

74. Richard Hell & The Voidoids

Blank Generation

(Sire, 1977)

“I was saying let me outta here before I was even born – it’s such a gamble when you get a face!” He’ll go down in history as the guy whose safety-pinned shirts and shock of spiked hair invented the punk look (later “borrowed” by Malcolm McLaren to dress the Sex Pistols), but Richard Hell remains strangely underrated compared to his CBGB peers, chiefly known for just one song – the epochal ‘Blank Generation’. Never much of a player (though he was briefly a member of Television with co-conspirator and fellow teen runaway Tom Verlaine), Hell was the consummate punk rock star; what he lacked in chops he made up for in charisma and spittle, elastic yelps and seedy street poetry – although the secret weapon in the Voidoids’ line-up was the mighty Robert Quine, whose erratic, sinewy guitar lines are a like match to Hell’s gunpowder on highlights like the flawless ‘Love Comes In Spurts’.

73. Annette Peacock

I’m The One

(RCA Victor, 1972)

Moving in the same professional circles as Albert Ayler, Paul Bley and Salvador Dali, jazz composer/vocalist Annette Peacock threw her lot in with fusion songcraft on I’m The One. Most tracks follow a similar formula, but it’s a good one: treacly grooves topped with wibbling oscillators and Peacock’s histrionic vocals. For much of the record, her voice is squeezed through filters or bitcrushed to buggery; elsewhere, she’s eerily reminiscent of Bowie in full Ziggy Stardust flight (Bowie, incidentally, was a paid-up fan). Exhilarating cosmic funk, and even after a couple of reissues, still dismally under-appreciated.

72. Fleetwood Mac

Rumours

(Warner Bros, 1977)

You’d think that by now Rumours would be swallowed up by its Behind The Music-sized mythology — all the trauma and drama of the bacchanal-fueled sessions, the disintegrating romantic relationships, or even the damaged tapes — but you’d be wrong. This is the Mac at the height of their powers, perfecting a bend-not-break formula for rock excess (that would eventually fail on Tusk). Each of the five heads of the chimera have their moment, but this is sum-greater-than-parts material, and more lovesick than ‘Don’t Stop’ would suggest (and even that is about running from the pain of the past). After its 40 minutes, you’re left just like the band: beaten and battered, tossed around and discarded; haunted by loneliness with nothing to show for it but shattered illusions of love and a silver coke spoon.

Brad Rose (Digitalis): “I can’t count how many parties I’ve been to where someone stupidly puts on Rumours. Sure, it’s a pop record, but it’s so visceral and emotionally draining that I can’t imagine anyone hearing the repetitive chorus of the album’s first song, Lindsey Buckingham wailing “I’m just second hand news,” and wanting to have a good time. It’s a therapy session that’s sold millions-upon-millions of copies.

Brad Rose (Digitalis): “I can’t count how many parties I’ve been to where someone stupidly puts on Rumours. Sure, it’s a pop record, but it’s so visceral and emotionally draining that I can’t imagine anyone hearing the repetitive chorus of the album’s first song, Lindsey Buckingham wailing “I’m just second hand news,” and wanting to have a good time. It’s a therapy session that’s sold millions-upon-millions of copies.

“Rumours is the sound of marriages and friendships being put into the grinder and disintegrating right in front of you. As a soap opera it’s interesting, but as an exquisitely-crafted pop album it’s endlessly compelling and unavoidable. That raw fragility, though, is where Rumours thrives. Sonically, Fleetwood Mac are so totally dialed-in that the songs are stripped bare until only the most important elements remain. Stevie Nicks’ voice is impossible to ignore, cementing her place on the Mt. Rushmore of rock vocalists. Captivating arrangements bolster the earworm melodies from Buckingham, Nicks, and Christine McVie, making a lyrically-brutal tune like ‘Go Your Own Way’ into a sing-a-long anthem.

“Their personal lives may have been wrecked, but it was the fuel that pushed Fleetwood Mac from just another pretty good ’70s rock band into the pantheon. Rumours is simply timeless.”

71. Art Ensemble Of Chicago

Les Stances à Sophie

(Universal Sound, 1970)

Inspired by a sojourn in hip and happenin’ ’70s Paris, Les Stances A Sophie finds the Art Ensemble Of Chicago in an unusually charming and chipper mood. “Your fanny’s like two sperm whales / Floating down the Seine”, howls Fontella Bass, peppering the funky breakbeats and clattering brass of enduring anthem ‘Theme De Yoyo’ with unparalleled sass and soulful sensuality. Unique to their catalogue, the album is striking in its marriage – or perhaps more accurately, shotgun wedding – of free jazz and fusion funk grooves, proving that order and chaos really can compliment each other beautifully, if the players are sensitive and skilful enough to pull it off.

70. The Residents

The Third Reich ’n Roll

(Ralph, 1976)

What do you need to know? It’s two side-long mash-ups of mid-century pop cultural references, from ‘Yummy Yummy Yummy I’ve Got Love In My Tummy’ to ‘Hey Jude’, sung in deranged cartoon voices by synth-prodding lunatics with eyeballs and skulls on their heads, with absolute virtuosity blurring with deliberately hamfisted changes, and a constant maniacally-realised military/Nazi theme overlaid on it all. It’s the precursor for everything from The KLF to Matmos, The Church of the SubGenius to The Fall. If, knowing all this, you need to question why it’s on the list, you’re in the wrong place.

69. Sun Ra

Space Is The Place

(Blue Thumb, 1973)

Sun Ra’s quirky brand of afro-futurism was never really going to conquer the mainstream, but this 1973 album, tied into a trippy blaxploitation film of the same name, was his boldest and best shot at evangelising his outer-space ideology wider than the freaks and dropouts of the jazz underground. Objectively speaking, it’s neither his most challenging nor his most satifying work, but remains enduringly popular – largely down to the hypnotic, spiralling 21 minute long title track, certainly one of the most blistering versions of the song the Arkestra ever committed to record. Flip it over to float along with the astro-nautical travelogue ‘Sea Of Sound’, and finally blast off the cosmic chanting of ‘Rocket Number 9’.

Luke Abbott: “The deity know as Sun Ra was a messenger from another dimension sent to us to teach the lessons of freedom. “Space is the place,” he said; think further away, and let yourself be free to celebrate the majesty of the universe. This isn’t his most abstract work; it sort of drifts in and out of ‘correct’ jazz. Sometimes it’s like a slightly wonky big band is playing almost functional music, and at other times it seems to be totally free from any tradition or rules. It doesn’t really care though, as it would rather explore than stop to contemplate, and does so in a mockingly humorous way. If you’re the kind of person who prefers an interesting question to a sensible answer, then this record will speak to you.”

Luke Abbott: “The deity know as Sun Ra was a messenger from another dimension sent to us to teach the lessons of freedom. “Space is the place,” he said; think further away, and let yourself be free to celebrate the majesty of the universe. This isn’t his most abstract work; it sort of drifts in and out of ‘correct’ jazz. Sometimes it’s like a slightly wonky big band is playing almost functional music, and at other times it seems to be totally free from any tradition or rules. It doesn’t really care though, as it would rather explore than stop to contemplate, and does so in a mockingly humorous way. If you’re the kind of person who prefers an interesting question to a sensible answer, then this record will speak to you.”

68. Various

No New York

(Antilles, 1978)

Connected by location and association more than any musical similarities, the four bands on the seminal No New York compilation – sax-based punk-funker James Chance and his Contortions, Lydia Lunch’s Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, abstract noisemongers Mars and tightly-wound trio D.N.A. – represent a schism with the self-consciously trendy new wave set, rejecting the poppy immediacy perfected by Talking Heads, Ramones, Blondie et al in favour of abstraction, negative space, dismantled structures and downright tunelessness. The resulting coinage ‘no wave’ further defines their anti-style; a nihilistic yelp emanating from a trash-ridden Downtown still years away from yuppification. Compiled by Brian Eno (yet another appearance on our list by the former Roxy Music shape-shifter), the album is both a snapshot of a short-lived scene and a blueprint for the next decade of fringe music, from John Zorn and Bill Laswell to Sonic Youth and Swans.

67. Gil Scott Heron

The Revolution Will Not Be Televised

(Flying Dutchman, 1974)

An early career compilation with lasting influence, The Revolution Will Not Be Televised set the table for hip-hop with the proto-rap lyricism of the title track’s anti-media screed and the ratatat refrain on ‘No Knock’, and inspired neo-soul a generation later with a classic blend of soul, funk and jazz. Scott-Heron made up for what he lacked in range with a voice so rich and lyrics so resonant that the barbs still sting through the speakers today. He could do punchy (‘Lady Day and John Coltrane’), or laidback (‘Save The Children’), or mask his social commentary with whimsy and a sneer (‘Sex Education, Ghetto Style’, ‘Whitey On The Moon’), or aim his rhetorical cannon at his own community (‘Brother’). But his most poignant target was himself: “did you ever try to turn your sick soul inside out,” he moans on ‘Home Is Where The Hatred Is’, “so that the world…can watch you die?”

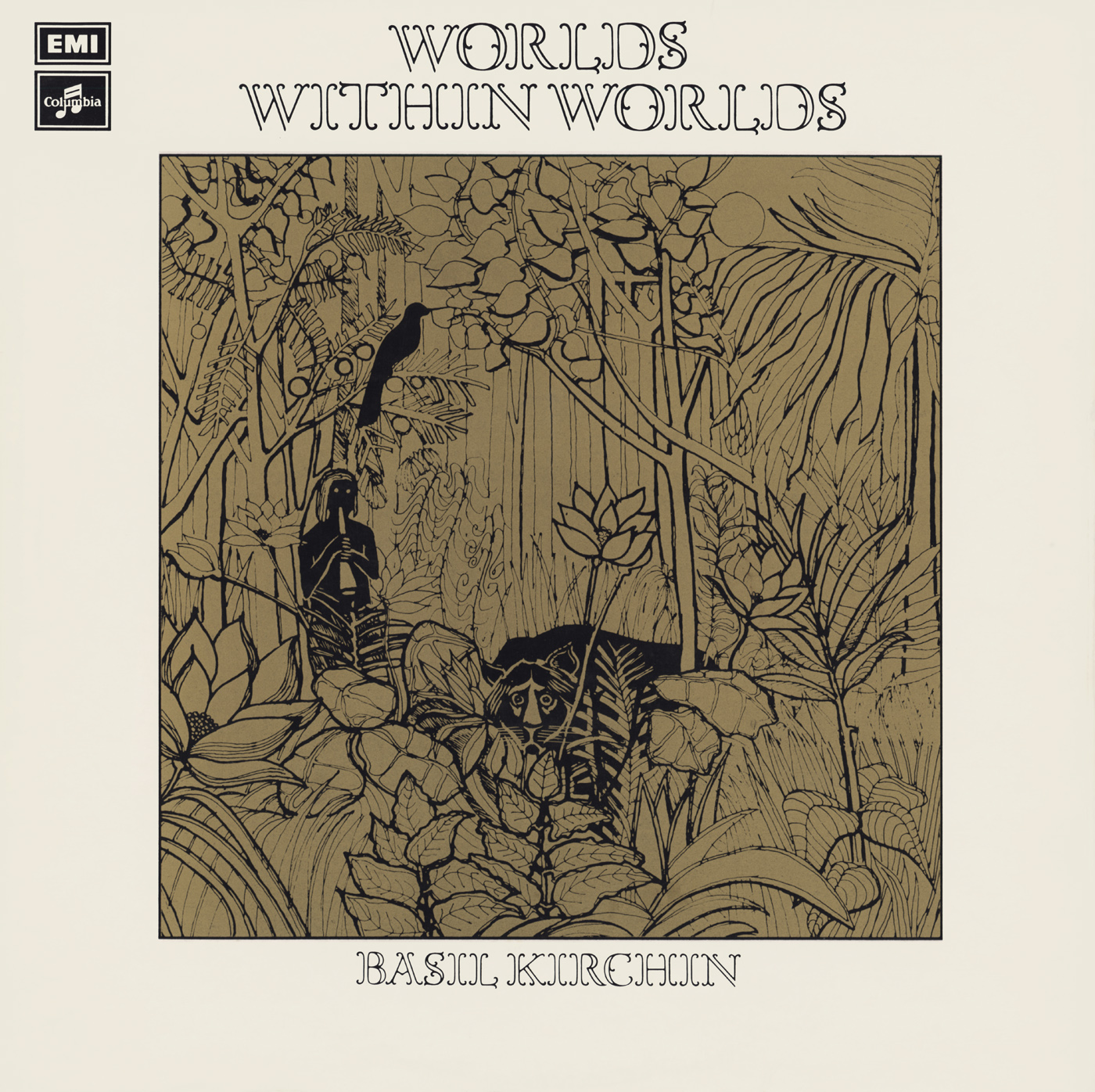

66. Basil Kirchin

Worlds Within Worlds

(Columbia, 1971 / Island, 1974)

Son of Hull, Kirchin had sizeable commercial success with his travelling big band The Kirchin Band in the mid 1950s, before turning his hand to frazzled film and TV scores. Worlds Within Worlds is his magnum opus, a pioneering collection of evocative electronic mood pieces, released in two instalments. 1971’s package hews closer to free jazz ,with contributions from the likes of Evan Parker and Derek Bailey blending with Kirchin’s electronic tinkering. 1974’s second instalment is the tripper affair – saturnine chamber music, blended with tweaked found sound (grunting gorillas, wittering children, jet engines) and pushed to the outer-limits. Kirchin has been sniffy about these works in retrospect, claiming the label forced him to water them down, but these muggy, murky compositions still sound thoroughly off-road. Head music for curious souls, and the best introduction to a composer who’s had to wait far too long to get his dues.

65. Shuggie Otis

Inspiration Information

(Epic, 1974)

A late bloomer, this one – marginalised in the 1970s, and finally given some spotlight time in the 2000s with a keynote reissue on David Byrne’s Luaka Bop label. With the likes of ‘Inspiration Information’ and ‘Strawberry Letter 23’ (from Freedom Flight) now Coke advert / wedding dance fodder, it’s strange to think that Otis’ fourth and best album was left to gather cobwebs for decades. It’s a wonderfully drowsy collection of self-produced psychedelic soul, full of neat flourishes: see the blinding-light funk of ‘Happy House’, the offbeat drum machine shuffle of ‘XL-30’ and ambient waltztime interlude ‘Pling!’. And then there’s the small matter of ‘Aht Uh Mi Head’, which manages to sound lush and dozy

64. Lou Reed

Live: Take No Prisoners

(Arista, 1978)

Berlin may be his masterpiece, and Transformer the gateway drug, but no record sums up Lou Reed’s 1970s output better than Take No Prisoners, a live album recorded at New York’s Bottom Line in 1978. At this point, Reed was a veteran on his eighth album, but still sharp-as-a-pin and thoroughly in love with his own barbaric persona and acid tongue. Opening with a sprawling ‘Sweet Jane’ and skronking sax-enhanced ‘I Wanna Be Black’, the rock’n’roll animal is on unstoppable form in the ad lib department, delivering virtually every line with a quick-witted addendum or off-the-cuff aphorism, taking particular delight in laying into critics and celebrities (Robert Christgau gets it in the neck, as does Barbra Streisand). By the second half things are delirious to the point of absurd, with ‘Street Hassle”s junkie death spoken word section delivered like a healing hands sermon – and that’s before the quarter-hour version of ‘Walk On The Wild Side’. “It’s not only the smartest thing I’ve done, it’s also as close to Lou Reed as you’re probably going to get, for better or for worse,” as he told Rolling Stone that year.

63. Caetano Veloso

Caetano Veloso

(Polygram, 1971)

Or, wallow with Caetano. As the biggest name in the Tropicalismo movement of the late 1960s, Veloso became something of a national talisman to a Brazil struggling under military rule. Recorded during his forced exile in London, Caetano Veloso – known as A Little More Blue to distinguish it from his other self-titled albums – is a stark contrast with the swingin’ burlesque of his 1968 debut and its more nuanced 1969 follow-up. Instead, it’s a downbeat exploration of marginalisation – explicitly Veloso’s disconnect from his homeland, but one with equal resonance for the heartbroken or the downtrodden.

Touches of the quirkiness of old are present – UFOs, Faustian pacts, the glossolalia solos on ‘Maria Bethânia’ and ‘Asa Branca’ – but this is Veloso at his most restrained and plaintive. That voice, sweet as nectarine but loaded with sorrow, carries some gorgeous originals (‘A Little More Blue’, ‘London, London’). We nearly plumped for Veloso’s wildly experimental 1972 LP Araçá Azul, but, in the end, we couldn’t deny Veloso’s most affecting record – 35 minutes of wistfulness on wax.

62. David Bowie

The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars

(RCA Victor, 1972)

Davie Jones had to become Ziggy Stardust before he truly became David Bowie. The distillation of his hard rock turn on The Man Who Sold The World and the artfulness, androgyny and ambiguity of Hunky Dory, Ziggy Stardust was Bowie cribbing from his inspirational contemporaries (Iggy Pop, Lou Reed, Marc Bolan) and creating something entirely new: a meta examination of The Rock Star itself. The album’s lasting influence can’t be understated: anyone exploring alienation, dystopia, messianic salvation and the nature of celebrity owes their livelihood to Bowie, from Prince and Marilyn Manson to Lady Gaga and Lana Del Rey. Musically and stylistically, Ziggy Stardust would influence punk and hair metal, the New Romantics and the New Wavers, and — in a strange feedback loop — would inspire some of Iggy Pop and Lou Reed’s greatest music.

61. Conrad Schnitzler

Rot

(Self-released, 1973)

Conrad Schnitzler had his fingers in a lot of pies – an original member of both Tangerine Dream (with Klaus Schulze and Edgar Froese) and Kluster (with Hans-Joachim Roedelius and Dieter Moebius), he found himself at the center of German electronic music in the 1970s, whether he liked it or not. You see he never regarded himself as a musician, rather as an artist in the grander sense, who just happened to work in a variety of different disciplines.

Rot was his first solo album, and saw him ditch the quirky sound-art of his prior work (with Kluster, especially) in favour of two extended compositions for the EMS Synthi. These pioneering pieces set a high water mark for electronic music – seemingly formless and improvised, careful listening reveals overlays of rhythm, harmony and even melody. It’s hardly easy listening, but Rot’s alienating synthetic tones are fascinating and even, at times, beautiful.

60. Flower Travellin’ Band

Satori

(Atlantic, 1971)

Ecstatic Japrock crunch, and easily one of the most underrated hard rock records of the early 1970s. The Flower Travellin’ Band started life as a covers act in the late 1960s, spreading the gospel of Cream and Jefferson Airplane around Tokyo. Five odd years later, they’d made Satori – an album which out-wigs many of their forbears, and stands toe-to-toe with Sabbath and Led Zep. Hideki Ishima’s feverish guitar-playing is full of clever psychedelic flourishes, but, really, this is all muscle – an impressive exercise in heavy rock flexion. The word “satori” refers to a moment of catharsis, and vocalist Joe Yamanaka sounds like he’s having a couple per track (we’ll take his banshee wail over Robert Plant’s double-barrelled cringe assault any day, incidentally).

59. The Modern Lovers

‘Live’

(Beserkley Records, 1977)

Jonathan Richman may not have been the decade’s most influential act, but he’s one of the few to have been influential not once but twice – first, with the Modern Lovers’ early punk recordings (‘Roadrunner’, a stand-out from belatedly released demo collection The Modern Lovers, was a Sex Pistols favourite), and then with the naive, gentle rock that he pursued in the second half of the ’70s.

The Modern Lovers 2.0 favoured intimacy over intensity, celebrating the subtleties of suburban life and using childish imagery to evoke nostalgia, and they’re never captured with more charm than on their live recordings. ‘Live’, tellingly, has been reissued more than plenty of the group’s studio albums, with the Lovers’ most-loved songs stretched out into something between Jackanory and a call-and-response game, peaking on the ludicrous eight-minute version of ‘Ice Cream Man’ that closes Side A and a heart-warming rendition of ‘Morning of our Lives’ on the flip.

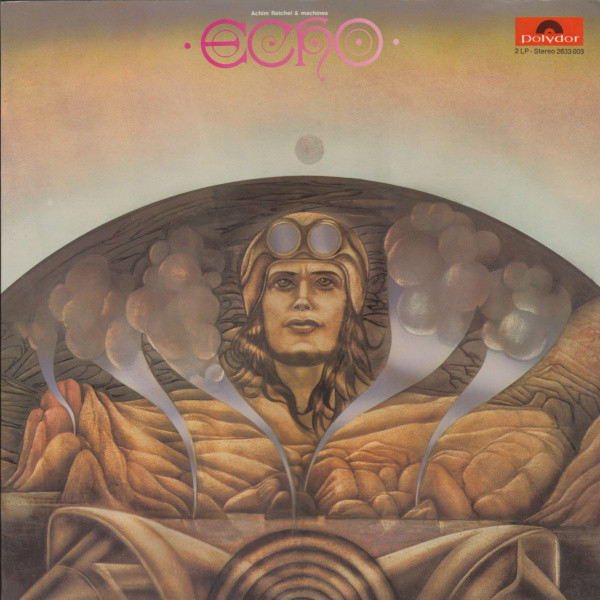

58. Ar & Machines

Echo

(Polydor, 1972)

Now there’s a title that does what it says on the tin. Having fronted The Rattles, Germany’s premiere cheeky-chappie beat combo, in the mid-1960s, Achim Reichel somehow found his way to this long, heady, benthic-zone-deep album of early space-rock. AR’s genius is to slather everything in echo – what might have been a perfectly serviceable collection of prog jams becomes something much more exotic and amphibian. ‘Einladung’ prefigures Ariel Pink and Gary War’s hispter swampsong; ‘Das Echo Der Vergangenheit’ collapses into a mess of spoken word, then emerges from the chaos, phoenix-like, as an ambient drone piece. Four decades on, it’s achieved a second life as something of a chill-out staple. Saddle up thy beanbag, traveller…

57. Stiff Little Fingers

Inflammable Material

(EMI, 1979)

Striking, iconic and just the right amount of ragged – and that’s just the album art. Like Inflammable Material‘s cover, Stiff Little Fingers’ debut album sports a balance between sleek and scruffy that’s somewhere between the US and the UK: yes, the group were from Belfast and mostly wrote about Belfast issues, but the twang of ‘Here We Are Nowhere’ and ‘Barbed Wire Love’ sits neatly alongside both the Stateside punk of the ’70s and later groups like Minutemen. The best of both worlds, then, though try telling that to the councillor who got them banned them from playing Newcastle after hearing – and completely misinterpreting – ‘White Noise’.

56. Harold Budd

The Pavilion Of Dreams

(Editions EG, 1978)

Harold Budd’s crowning achievement, The Pavilion of Dreams represents a milestone in what many like to call “new age” music. In fact, it’s anything but – Budd himself notoriously despises the term and it’s not hard to hear why. His compositions are light and airy, but complex and decidedly well-realised, and while The Pavilion of Dreams wasn’t necessarily a huge commercial success, its set of weightless compositions remain incredibly influential.

The Cocteau Twins, for example, were so fascinated with the album’s centerpiece ‘Madrigals of the Rose Angel’ that, after requesting the rights to record a cover version, they embarked on a long and fruitful collaboration – Robin Guthrie and Budd are still composing together today. Ambient music (if you could even label it that), never sounded quite the same again.

55. Faust

The Faust Tapes

(Virgin, 1973)

Still most notorious for being sold at the price of a single (50p – those were the days), The Faust Tapes confused almost everyone who purchased it, which unbelievably was a good 50,000 shoppers. Fans of the band struggled to get to grips with the fact that they’d dropped the chunky krautrock elements of their earlier records, and new listeners (which, let’s be honest, made up most of the sales) were appalled to hear what they regarded as non-music.

40 years later, it still sounds bonkers, and that’s really the charm. Part of the reason it sounds the way it does is down to the process. To mark the band’s Virgin record deal, one of the label’s technicians put together a series of tracks culled from the band’s private recording sessions, and engineered it into a quirky audio collage. What resulted was one of the oddest records to invade the homes of the British listening public, and while plenty of the LPs were no doubt returned to the store (or dumped in a charity shop) after a single play, the seeds of a sound that was truly anarchic and defiant were certainly sown.

54. U-Roy

Dread In A Babylon

(Virgin, 1975)

Oh god, there’s nothing worse than discussions of classic reggae that are full of sniggering spliff gags, but there’s no other way to approach U-Roy: this man, especially on this album, is simply a personification of marijuana. The way his voice swerves back and forth from rough to smooth, from bark to croon to delicate scatting, is almost enough to give you a contact high in itself – and the way love, sex, anger, belligerence, tenderness, revolution and spiritual pronouncements blur together in his lyrics into a heady stew of bleary obsession without boundaries can make your head spin. It’s utterly befuddled and befuddling but delivered with such unfaltering rudeboy certainty, and held together by such solid dubwise production, that it feels like it should make sense. It doesn’t, though, but that’s its beauty.

53. Heldon

Heldon 6 / Interface

(Cobra, 1977)

One of the grand-pères of experimental French rock, Richard Pinhas put out seven albums of electronically assisted prog with Heldon from 1974-1977. It’s a wildly varied little run, ranging from Robert Fripp-besotted dreaminess (Heldon II) to opaque where’s-the-Moog-manual electronics (Heldon V). As per the title, Interface is the point where Pinhas’ various interests meet most happily – navel-gazing is kept to a minimum, and the electronic engine room is working at a fierce lick. At its best (the galloping electronic squelch of the ‘Soupcoupes Volantes’ tracks; knuckle-dragger ‘Interface, Pt. 2’) Interface is genuinely exhilarating. File alongside another French electro-rock bruiser from the same year, Zed’s Visions Of Dune.

52. Stevie Wonder

Innervisions

(Tamla, 1973)

The decade’s most influential and important pop musician, it’s tough to pick just one of the albums from Stevie Wonder’s unparalleled classic period. But Innervisions is a sweeping artistic statement: personal and political, solemn and celebratory, and an all-killer no-filler album where he (almost literally) does everything. There are polemics against drugs and Nixon, kaleidoscopic ballads and somber lullabies, and where do you start with the singles? ‘Living for the Golden City’ is a seven-plus epic where he played every instrument and sang with throat-burning intensity about race relations in America; the salsa-flavored ‘Don’t You Worry ’bout a Thing’ foreshadowed game-spitting rap skits; and the irresistible ‘Higher Ground’ is so uplifting that it helped break through the coma that he fell into just days after the album’s release. Pure genius.

51. Nurse With Wound

Chance Meeting on a Dissecting Table of a Sewing Machine and an Umbrella

(United Dairies, 1979)

Fun as all the cool context is with NWW – their scholarship of the avant-garde, the album title derived from proto-surrealist poet Isidore-Lucien Ducasse aka Comte de Lautréamont, the off-kinky artwork – you crucially don’t need any of it, or any background knowledge at all, to get weirded out by the music. The guitar screeches, drones, games with scale and reverb, it’s all so perfectly abstracted, it needs no reference points at all – it’s really closer to a drug than any accepted form of music really, so directly does it fuck you up, and so difficult is it to relate to any kind of quotidian experience. If you ever find yourself in a state of disenchantment with genres and scenes, if ever you feel jaded, snowblind or glutted with music, this is exactly the refresher you need: go back to this uniquely powerful brain-scourer of an album, and you’ll find your tastes rejuvenated.

50. The Specials

The Specials

(2-Tone Records, 1979)

Coventry’s finest export had impeccable timing. Arriving at an explosive moment in British social history, with far-right oiks on the rise and barging their way into punk with their moronic terrace anthems and Sham 69 patches and bloodlust, The Specials ran on an explicitly anti-racist, anti-Thatcher ticket, introducing their beloved Jamaican ska into the punk milieu and rallying an entire subculture under the 2 Tone banner.

Many of the tracks on their debut are perky, brass-filled covers (including ‘Monkey Man’, ‘Too Hot’ and ‘A Message To You Rudy’, given the seal of approval by guest trombonist Rico Rodriguez of the Skatalites), but their self-penned songs provide a vital undercurrent of seething anger, documenting the dour, beans-for-tea-and-a-punch-up-for-afters world of late ’70s England, as on ‘Stupid Marriage’ (“He thinks that she’ll be happy when she’s hanging out the nappies”) and ‘Nite Klub’ (“I won’t dance in a club like this / All the girls are slags and the beer tastes just like piss”). (The distrust of women and their bodily functions is depressingly palpable.) Meanwhile, first-time producer Elvis Costello wisely takes a light-touch approach at the controls, preserving the raucous energy of a band who were first and foremost a live proposition.

49. Tangerine Dream

Phaedra

(Virgin, 1974)

Tangerine Dream’s earlier albums might have been more experimental, but Phaedra marked a point in the German band’s career that would see them influence multiple generations of wide-eyed synthesizer obsessives. It was the inclusion of Christopher Franke’s Moog sequencer that pulled Tangerine Dream in such a different direction, and the hypnotic, repeating patterns it created caused not only a shift in the band’s own sound, but in electronic music in general.

On Phaedra we can hear a band straddling their experimental tendencies and their desire for more commercial acknowledgement – and for many fans it represented the beginning of the end. The albums that followed (Rubycon, especially) are also worth grabbing, but the band never again nailed such a perfect collision of harmony and dissonance.

48. Joni Mitchell

The Hissing of Summer Lawns

(Asylum, 1975)

There’s a price of entry to this one. You have to accept jazz fusion, and you have to accept ultra-dense literary-reflective ’70s lyricism, and these are not easy things to do, especially if you like music to be immediate in its impact. But then, somehow, once you do finally break that glossy surface, paradoxically you realise that this IS an immediate album, and also that it’s actually worlds away from any standard fusion noodle or me-generation introspection. And of course the reason for this is that Joni is one of the most powerful personalities in all of post-60s-counterculture music, not to mention strongest songwriters. Dylan? Neil Young? Bollocks – Joni eats them all for breakfast. And once you let yourself get inside Hissing, you realise it’s not just her masterpiece, but one of the masterpieces of a whole generation. It’s got folk, jazz, soul, Broadway; it’s a painting, it’s a poem, it’s a Great American Novel, its a musical… and it’s a really, really good album.

Oren Ambarchi: “I love that feeling when a pop record slowly reveals its beauty and hidden depths to the listener. For me, it usually takes a few intense listens for it to sink in, but once it does I become completely and utterly infatuated. This is definitely one of those records that I have played the shit out of. Friends always go on to me about Court & Spark but when it comes to Joni, this is THE ONE for me. Worth it alone for the haunting masterpiece ‘Edith & the Kingpin’ – but believe you me, this is a sublime, rich and hypnotic opus with dark observational lyrics that have to be some of the greatest in pop, with deceptively simple playing and arrangements that are completely seductive – I could listen to the outro of the title track forever. ”

Oren Ambarchi: “I love that feeling when a pop record slowly reveals its beauty and hidden depths to the listener. For me, it usually takes a few intense listens for it to sink in, but once it does I become completely and utterly infatuated. This is definitely one of those records that I have played the shit out of. Friends always go on to me about Court & Spark but when it comes to Joni, this is THE ONE for me. Worth it alone for the haunting masterpiece ‘Edith & the Kingpin’ – but believe you me, this is a sublime, rich and hypnotic opus with dark observational lyrics that have to be some of the greatest in pop, with deceptively simple playing and arrangements that are completely seductive – I could listen to the outro of the title track forever. ”

47. La Düsseldorf

La Düsseldorf

(Nova, 1976)

Famously touted as “the soundtrack of the eighties” by Bowie, La Düsseldorf were one of krautrock’s most accessible and most successful acts. Originally formed as a Neu! side project by brothers Klaus and Thomas Dinger, La Düsseldorf became their focus after Neu! broke down beyond repair in 1975 (several tracks on the group’s last album are actually performed as Neu!-La Düsseldorf). Klaus dropped his drums to hone his guitar – by his own admission, pushing for for a popper sound in the process – and often it’s his guitar-playing that sets La Düsseldorf apart, squealing and soaring over a reliable motorik beat on the album’s first half, and drifting in and out of focus on ‘Silver Cloud’. Closing track ‘Time’, meanwhile, combines guile and grandeur in ways that Pink Floyd could only dream of.

46. Funkadelic

Maggot Brain

(Westbound, 1971)

Fuck ‘Free Bird’: wouldn’t the world be a better place if concert knuckleheads requested ‘Maggot Brain’ instead? As the legend goes, during a typically acid-fueled recording session, George Clinton instructed Eddie Hazel to imagine he had been told his mother had died, but then told that she was alive. Apocryphal or not, as the solo’s melancholy and devastating loss give way to mind-melting fuzz frenzy, it’s impossible not to chalk it up to a stroke of George Clinton’s singular genius. While the title track is worth the price of admission alone, Funkadelic didn’t stop there, reworking the Parliaments’ R&B break-up song ‘What You Been Growing’ into the blown-out, gospel-influenced ‘Can You Get To That’, laying down a classic funk-rock anthem in ‘Hit It And Quit It’, and invoking the spirit of Hendrix on ‘Super Stupid’. Obviously never ones to shy away from the weird, black folk rhymes found new life on the low-lidded groove of the increasingly warped ‘You And Your Folks, Me And My Folks’, the feel-good ‘Back In Our Minds’ toyed with an elastic jaw harp, and ‘Wars of Armageddon’ takes on the sexual revolution and civil rights with a chaotic found-sound bonanza.

James Ginzburg: “To stumble upon your brother’s brain leaking from his fractured inert skull, long-dead, maggot infested, would create ripples of consequence for any man or woman, and whether myth or not, it is a powerfully disturbing image upon which, plinth-like, George Clinton placed the ten minute title track of Funkadelic’s third album, Maggot Brain.

James Ginzburg: “To stumble upon your brother’s brain leaking from his fractured inert skull, long-dead, maggot infested, would create ripples of consequence for any man or woman, and whether myth or not, it is a powerfully disturbing image upon which, plinth-like, George Clinton placed the ten minute title track of Funkadelic’s third album, Maggot Brain.

Despite owning the album for ten years, I have listened to the other tracks on the LP at most five times, in contrast to the thousands of hours that I have spent listening to the instrumentation accompanying Eddie Hazel’s heart stabbing guitar solo appear and disappear, as if the other musicians had walked into their living room and found their parents yelling, at each other’s throats, drowning in hatred, sorrow and love, the consequence of infidelity or perhaps the unbearable loss of a loved one – and then quietly, so as not to be heard, crept away to a safe distance so that they could hear only the muted tone of painful screamed words, the precise meaning lost somewhere in an opaque sea of a melancholy and beautiful uncertainty. ”

45. New York Dolls

New York Dolls

(Mercury, 1973)

The New York Dolls were a motley crew of outer-borough troublemakers that made Manhattan their playground, and they tore down the studious bloat of progressive rock with a sloppy kiss and a knowing wink. The Dolls swallowed influences like a handful of pills: rehashed rock’n’roll riffs a la Chuck Berry and The Stones, metallic proto-punk overdrive from MC5 and The Stooges, the androgynous glam of Lou Reed, lower Manhattan drag queen ferocity, girl group pop melodies… everything all the time, pushed to the breaking point. The job of harnessing the band for their self-titled debut fell to the somewhat-unlikely Todd Rundgren, who somehow managed to hold it all together, capturing their hot transvestite mess of a stage show on tape.

Johnny Thunders and Sylvain Sylvain’s guitars still sounded like lawnmowers (as an infamous review maintained), Jerry Nolan and Arthur Kane managed to ride the rails and David Johansen is particularly unhinged, prowling like a street-walking cheetah with a hide full of napalm: “And you’re a prima ballerina on a spring afternoon,” he sneers on signature tune ‘Personality Crisis’, “Change on into the wolfman howlin’ at the moon, ohwooo.” The Mercer Arts Center where the Dolls made their name would collapse a week after the album’s release, and the band themselves would implode after the next album, but the damage was already done.

44. John Carpenter

Assault on Precinct 13

(film released 1976)

John Carpenter’s Assault on Precinct 13 soundtrack might have only been available as a bootleg until the mid-’00s, but its influence and reach went far beyond its availability. Carpenter’s sparse, minimal score was partly that way because of the limitations of the complicated technology, but it not only worked well in context with his eerie thriller, but also on its own, where the theme slowly began to take on a life of its own.

Not only did it end up being sampled by Afrika Bambaataa (on ’86’s ‘Bambaataa’s Theme’), but Bomb the Bass used it as the framework for their 1988 hit ‘Megablast’. This in turn ended up being used as the theme for ’89 Commodore Amiga game Xenon 2, and soon a generation of children would know Carpenter’s theme well enough to hum the lead synth line, but still couldn’t go out and purchase the soundtrack legally.

Lasse Marhaug: “This album shouldn’t be on this list. Why? Because the full album of John Carpenter’s seriously amazing 1976 synth score to his seriously amazing High Noon-remake wasn’t available to buy until 2003. And that was just CD – the vinyl didn’t arrive until 2013. (That’s last year). But, history books are written by internet losers like us, and this recorded-in-three-days score is so good we’ll just pretend it came out back in the mid-’70s until it becomes the truth.

Lasse Marhaug: “This album shouldn’t be on this list. Why? Because the full album of John Carpenter’s seriously amazing 1976 synth score to his seriously amazing High Noon-remake wasn’t available to buy until 2003. And that was just CD – the vinyl didn’t arrive until 2013. (That’s last year). But, history books are written by internet losers like us, and this recorded-in-three-days score is so good we’ll just pretend it came out back in the mid-’70s until it becomes the truth.

“I was born in 1974, so I don’t remember much of those days anyway, but when I play the Assault on Precinct 13 2003 Compact Disc (as I do pretty much every day of life), I’m reminded of not just how grim/nihilistic/sexy the 1970s were, but also that if John Carpenter had flopped with Halloween two years later, he could’ve had a glorious career as a composer. Mandatory listening, kids. Really, mandatory.”

43. Robert Ashley

Automatic Writing

(1979, Lovely Music)

Influenced by his own problems with a mild form of Tourette’s Syndrome, avant garde composer Ashley decided to compose a piece of music that would act as an exploration of involuntary speech, and it took him five years of experimentation to do it. While his Tourette’s would break up his speech regularly, his attempts at recording it kept failing – he felt as if he had too much control, and was actually simply faking the outbursts rather than allowing them to happen normally. To achieve a proper recording, he eventually decided to perform the session in Summer, when Mills College (where he worked) would be empty, and Automatic Writing was born.

It’s a recording that, while bearing many of the hallmarks of Brian Eno’s ambient recordings, is anything but background music. Instead it is various recordings of background music mixed together, guided by the barely-intelligible voice of Ashley himself. It sounds almost alien, like a series of distant transmissions blended into a harmonic soup, and its allure is unavoidable.

Pete Swanson: “Automatic Writing was Robert Ashley’s attempt to document his own mild form of Tourette’s syndrome, which generally manifested in his muttering to himself in unintelligible language. He wanted to not only document his own spontaneous vocalizations, but he wanted to produce a work that reflected both the unpredictability of his illness, but also his work in opera. He assigned four voices to the recording, which included recordings of his own voice, a woman’s voice translating and repeating his utterings in French, a self-switching synthesizer, and a track of an unknown organist rehearsal recorded from a few rooms away.

Pete Swanson: “Automatic Writing was Robert Ashley’s attempt to document his own mild form of Tourette’s syndrome, which generally manifested in his muttering to himself in unintelligible language. He wanted to not only document his own spontaneous vocalizations, but he wanted to produce a work that reflected both the unpredictability of his illness, but also his work in opera. He assigned four voices to the recording, which included recordings of his own voice, a woman’s voice translating and repeating his utterings in French, a self-switching synthesizer, and a track of an unknown organist rehearsal recorded from a few rooms away.

“Each voice (aside from the translation) operates outside of the influence of the other voices, but there is an odd synchronicity and balance throughout the recording. Different voices weave in and out of each other…elements fade away…your attention drifts. You forget you’re listening to music. You wonder what the recording is that your neighbors are playing…or if the sound of the street has been amplified somehow… It starts to feel like sound is seeping through the floorboards and slowly penetrating your DNA. Nothing about this piece makes sense and it subliminally projects a soft and inviting kind of madness that no other artist has ever even come close to documenting.”

42. The Slits

Cut

(Antilles, 1979)

The Slits were veterans by punk standards when their debut album finally arrived, having supported The Clash on their 1977 White Riot tour and delivering two exhilaratingly slapdash Peel Sessions which the great man deemed “magical”. By the time they pitched up at a farm in Surrey to record Cut, they’d lost a member (Palmolive, who went off to join The Raincoats and was replaced by future Banshees drummer Budgie) and gained a vital guiding hand in the shape of producer Dennis Bovell, whose dub and reggae expertise chimed with their tastes and helped cultivate Cut‘s masterful balancing act between febrile, metronomic energy and slippery, spacious grooves. Teen singer Ari Up cements the no-fucks-given DIY attitude with her crooked trills and yelps, her strange German-Jamaican-English voice exhorting us to “do a runner!” after stealing from a “Babylonian” (‘Shoplifting’) or mocking girls’ obsessions with “spots, fat and natural smells” (‘Typical Girls’). Playful and savage, confrontational and contradictory, Cut still sounds as wild and untamed as the mud-caked cavewomen staring us down on the sleeve.

41. Ornette Coleman

Science Fiction

(Columbia, 1971)

The title is perfect here. Even more than Sun Ra – where the sci-fi imagery is scrambled together with the mythic, the cosmic and the ancient – Ornette Coleman’s skronk sounds futuristic. The precision and complexity of each of the constructions on this album is absolutely mind-frazzling, the rhythms seeming humanly impossible, and the tightness with which they’re locked together doubly so. This is jazz that feels as close to Autechre as it does to Louis Armstrong. Yet it’s freakishly listenable too, with every track its own distinctive world, that playing precision matched by song structures, and a willingness to incorporate populist and recognisable sounds too – so there’s the electric-Miles filtered funk underpinning ‘Rock the Clock’, the abstracted soul of vocal tracks ‘What Reason Could I Give’ and ‘All my Life’, and the disoncertingly straight bebop of ‘Law Years’ all incorporated into the sci-fi narrative.

40. Wire

Pink Flag

(Harvest, 1977)

Pink Flag came out in the same year as The Clash’s first single. It’s a chronological quirk that seems to confuse the album’s standing as a quintessential post-punk record, but the art-schooled Wire were always running on a different clock. Older and more ambitious than the snotty kids in safety pins around them, they compensated for their own lack of musical training with an academically enriched take on rock and roll, making them perhaps the most consciously avant-garde of Britain’s late ’70s punk set. Their debut contains 21 ideas across 21 rapidfire songbursts, each one stretched, poked, toyed with and discarded as soon as it’s deemed exhausted – a process that usually takes less than two minutes. But Wire’s dry methodology never stood in the way of a razor-sharp riff or an air-punching hook, and Pink Flag’s marriage of beret-wearing intellectualism and taut, sinewy pop simplicity marked it out as unique among its lumpen kin and helped lay the foundations for the next generation of punk and hardcore.

39. Dadawah

Peace And Love – Wadadasow

(Wild Flower, 1974)

This is great for a couple of reasons. First and most obviously, the four long pieces based around Niyabinghi chanting and percussion – the same sound that so inspired London band Cymande, and later the mighty African Headcharge – are pure, heartfelt devotional music. And like the best devotional music, whether that be gospel, ragas, qawwali or a Bach mass, you don’t need to share a belief system or even be remotely “spiritual” to absorb and appreciate the hypnotic/meditational and profound feel-good qualities of the sound. Also though, this is a brilliant indicator of the diversity of early 1970s Jamaican music. Lloyd Charmers, the producer who gives the whole record a warm glow and dubwise sense of superhuman scale, was as happy working on soul-infused pop songs (including some that will appear higher up this chart), or his own deeply saucy songs, as on these deep and intense Rasta reflections; the various threads were not so very far apart at all.

38. Cerrone

Cerrone 3: Supernature

(Malligator, 1977)

Aside from its cover being the most gloriously disturbing glitterball-addled bare-chested French disco sleaze ever, this album is about as good an illustration as any of the high art of disco. ‘Give Me Love’ and ‘Love is the Answer’ are stunningly structured, with real strings and blaringly artificial synth sounds playing off each other as though they’d been dancing partners all their lives, and the steady changes taking their own sweet time to reach dance floor lift-off. ‘In the Smoke’ is a dreamy synthscape, while ‘Love is Here’ and ‘Sweet Drums’ are stomping two-minute teases. It’s the title track, though, which lifts it into true greatness – 10 minutes of high camp, all-synthetic delirium that just never gets tired – but there’s not a weak moment on the whole record.

37. Genesis

Selling England By The Pound

(Charisma, 1973)

Much is made of British eccentricity (and the pride that surrounds it), and rarely has it been so well realised as on Genesis’s sprawling masterpiece Selling England By The Pound. The album surprised many listeners who expected a continuation of Foxtrot’s rock direction rather than a return to the beardy folk of its predecessors, but the band’s willingness to confound expectations resulted in their most coherent and enjoyable collection of songs. Fairy tales, Tolkien, English folklore and the futility of modern life are all targets for Peter Gabriel as he jams wordy phrases into every nook and cranny, but it’s then-drummer Phil Collins (who we would soon take Gabriel’s place as vocalist) who gets to shine, taking the lead on standout track ‘More Fool Me’. Add in Tony Banks’ unforgettable synthesizer and Mellotron parts and you’ve got yourself a classic.

36. NEU!

NEU!

(Brain, 1972)

Let’s face it, even if this was only a 12” consisting of ‘Hallogallo’ and ‘Negativland’ we’d have been trying to bend the rules to get it in. Those two tracks are the motherlode of krautrock, both of them sounding as pristine and modernist now as they ever did. ‘Hallogallo’ in particular is just one of those grooves that could almost make you believe it exists outside of time. Like ‘Acid Tracks’ or ‘Energy Flash’, it’s just a perfect fusion of riff and rhythm that you could happily listen to modulating away for hours. The fact that the rest of NEU! is made up of basically awesome abstract alien planet gurglescapes, with the strange smacky instrumental ballad ‘Weissensee’ plonked in the middle, is just the icing on the cake.

Powell: “Feck, where do you start with this? I wasn’t there when it came out — I was somewhere deep in my father’s scrotum — but I think it goes to show how powerful this record is that it still has the kind of impact on people today that it definitely didn’t get at the time of its release. That’s often the way: truly great records get overlooked at first and then become influential many years later. And this record has famously influenced everyone from the biggest arena acts to basement noise freaks.

Powell: “Feck, where do you start with this? I wasn’t there when it came out — I was somewhere deep in my father’s scrotum — but I think it goes to show how powerful this record is that it still has the kind of impact on people today that it definitely didn’t get at the time of its release. That’s often the way: truly great records get overlooked at first and then become influential many years later. And this record has famously influenced everyone from the biggest arena acts to basement noise freaks.