If you had a penny for every time you heard some vintage creative type being described as ‘royalty’, you’d have a tidy little nest egg. But, in the world of sleeve design, Hipgnosis is, well, royalty.

Founded in 1968, Storm Thorgerson and Aubrey ‘Po’ Powell’s design agency was one of the dominant forces in album art throughout the subsequent two decades. Best known as the outfit behind Pink Floyd’s run of iconic covers, their clients included Led Zeppelin, Peter Gabriel, 10cc and ELO. Unless you’ve been living in a particularly well insulated cave, you’ll be well familiar with their aesthetic – colourful, brazen imagery, often based around arresting photography or gnomic symbolism. Their influence endures: in our feature on contemporary sleeve designers earlier this year, no company was namechecked as fervently or as regularly.

Neither Thorgerson nor Hipgnosis associate (and Throbbing Gristle and Coil member) Peter ‘Sleazy’ Christopherson are still with us, but Powell remains busy, having recently put out a retrospective tome, Hipgnosis Portraits. Joe Muggs caught up with the designer to talk about ’60s counterculture, acid casualties, and why the best artists need to be good with their fists.

Can we talk about growing up in Cambridge? Was there anything while you were growing up that hinted towards what you might end up doing?

Well in my late teens, the atmosphere was incredibly brotherly, and experimental. I would say that, unwittingly, we were part of a revolution that was happening culturally, particularly in England and in America – on the West Coast specifically. You could sense there was a lack of respect for authority, but in a different kind of way: it wasn’t done in an aggressive sense, but more in an intellectual sense.

The people I was with in Cambridge, like Syd Barrett and David Gilmour and Roger Waters and Storm too, of course – that crowd, who all hung out together, it was definitely a very intellectual crowd. It was a very philosophic crowd, very bohemian, we were all very much into the beat poets, philosophers, Baudelaire. As soon as Bob Dylan arrived, we were first there. We were all jazz freaks – Thelonius Monk was our hero. And in those days these people were unheard of, they weren’t the popular icons that you’d associate them as now.

So in a way, Cambridge, by chance, was quite cutting edge, and it wasn’t really that much of a surprise to me that, out of that circle of cutting edge freaky people, Pink Floyd emerged. The kind of music we’d be listening to would be John Cage, avant-garde experimental music. People knew what a Theremin was, and who Theremin was – these were things that were very rare indeed. I don’t want to sound elitist but it was definitely a very special group of people that came out of that Cambridge set.

But before you started discovering this esoteric stuff, what were you into?

Well, like anyone of my generation, I grew up on Elvis’ ‘Hound Dog’, then went through the rock’n’roll spectrum from Bo Diddley to Gene Vincent to Eddie Cochrane. The fashion of the day, before the Carnaby Street thing caught on, was really the beatnik look: hair combed forward to the fringe and wearing matelot t-shirts and very tight jeans. It was all that bohemian vibe already, but the music was definitely early rock’n’roll. Just around that time that we all left together to go to London – all the members of Pink Floyd and myself.

Dave Gilmour left to go and drive a van for Quorum, [iconic ’60s fashion designer] Ossie Clark’s company, while Syd and Roger had started Pink Floyd and were gigging around art schools and church halls developing the Pink Floyd sound – unwittingly, I should add, because they were really an R&B group at this stage – and there was a sort of infectiousness between us all that was to do with change.

We were on the cusp of not conforming, and by that I mean really consciously going against the grain and completely enjoying that process because nobody was there to tell us no to. It was a period of time when people – kids – shunned their parents. Much to the horror of my father, with the second world war still in the rear view mirror, we were growing our hair and all the rest of it, but it was really a case of get hip or get off the train. That’s just how it was.

The Nice – Elegy (1971)

It sounds like you were driven by a hunger to have something that other people didn’t have, is that fair to say?

Oh yes, absolutely. It was a hunger, that’s a very good expression. It was a hunger for things new and bright and colourful and to get rid of the drab and mediocre. You have to remember that all of the guys that came out of Cambridge were born just after or even during the second world war, and things were very difficult. We all experienced rationing as young children, it didn’t finish until 1954, in fact, when we were eight or ten – and that kind of thing sticks with you.

So as soon as new music came, as soon as colourful fashions came, one embraced them immediately. Also, it was easy to make money. It was a time and space where austerity gave way to freedom to earn and spend, and suddenly at 18 you could go out and buy your bright pink velvet trousers and your bright yellow Gohill’s high-heeled boots and your flowery shirt from Deborah & Clare in Beauchamp Place. It was suddenly a time where you could embrace those things because you could afford them, and that’s something that my parents’ generation could never do and could never understand.

So again, there was nobody there to say “you can’t do that” – you just did it. And that led to a little revolutionary group of people who just explored new things. Drugs, the I-Ching, playing [Chinese board game] Go…all those elements of east-meets-west. Alan Watts books. All those sort of mystical-meets-rock’n’roll-meets-making-money things… and trust me, as hippies, we weren’t really hippies, or we were hippies who at heart wanted to make money and get along in the world. Embrace the movement and get what you can.

Do you think the psychedelic drugs created the demand for colour and complexity, or were they just another exciting thing to add to the mix?

It was all part and parcel, it all arrived at the same time. It really was a movement – you know, like a movement in art. In art and in history there are movements, there’s the Renaissance, or Picasso’s Blue Period, or Dadaism, and this whole thing that was happening around ’65, ’66, ’67 was a colossal growth process, people embracing drugs, clothes, fashion, music, everything. It was something we all did together. I know “organic” is a very corny expression, but it was a very organic movement.

I’m not saying this was all a good thing by any means because there were casualties, including friends of ours who also came to London who died in tragic circumstances from too many drugs, or overdoses of psychedelia and not being able to cope with life afterwards, or getting involved in mysticism and Indian gurus and finding it was too stressful and too far removed from the norm they’d grown up with. Their lives ended sadly early.

So there was all that, but if you could survive it – well, the survival of the fittest was about the people who said, “you know what? I’m going to embrace this, I’m going to use it, I’m going to make money out of it, I’m going to enjoy it, I’m going to make it part of my lifestyle, and make my life good.” Those people all survived that period – and I think that would apply to all those people bar Syd Barrett.

Pink Floyd – Atom Heart Mother (1970)

So you mean people who could incorporate psychedelic experience and out-there philosophy into the real world, rather than chasing something metaphysical?

Yeah. The thing with Syd – and Syd and I shared a flat together when he was in his very bad period, just after he’d been slung out of Pink Floyd – was that his fear was all-enveloping. You could feel it, you could sense it, and any of us who’d taken psychedelics at the time were wary around him because you were very sensitive and you could feel his fear, his loss, his demotion from life – and part of you would want to keep away from it, it was like a sort of demon.

There’s a very famous story about Syd, but it’s absolutely true, that the very first time Syd ever went to Top Of The Pops, the first time the Floyd were on there, Syd looked at Roger and went “I bet John Lennon doesn’t have to do this.” Roger said, “what are you talking about? This is what we’ve been striving for, all the things we’ve done with Pink Floyd, we’ve been striving to get on Top Of The Pops, that’s the most important thing to secure the future of the band…”

But Syd didn’t want that, he didn’t want that sort of stardom, so in a sense he became a casualty of his own success. And there but for the grace of god go Storm and I – we could easily have gone down that route, but actually we invented Hipgnosis, worked with Pink Floyd each step of the way, and we all moved together forward and became successful together.

So at what point did you decide that design and collage were the things you were going to do?

That’s a very easy answer to give. I was always an artist, I was a painter, but I had no idea what I really wanted to do with my time. Then, when I was 17, I was working in the BBC as a scenery artist, and Storm, who was two years older and studying at the Royal College of Art, became my mentor in many respects. He guided me through a very uncertain period, and showed me different schools of photography – and the instant that he did that, I was enraptured.

I remember my first time in a darkroom, developing my first picture, which was of a Maserati car in Hyde Park, and Storm processing the film, putting the print in the developer: as I watched the picture coming through like an alchemical process, I was totally engaged, I got goosebumps all over me. I said, “Storm, this is magic, I have to do this – this is the thing I have to do.”

Then we joined forces unwittingly together, just starting to do photographs together. The interesting thing about Storm and me was that he was highly creative, highly irrational, highly irritable and very intense – but I had an acumen for business and an acumen for style, and when you combine those two personality types together, we hit on something that worked very well together. That was the secret of the early beginning, we realised we both had attributes we could give to each other to create an art house.

There was a third part to Hipgnosis, in Peter Christopherson, though, right?

What happened was that Storm and I had struggles in those early years of Hipgnosis – I won’t say they were easy at all. We were a young, budding creative art house and it was learn-as-you-go, nobody gave us the ground rules, and we were working in a world that was extremely resentful of the kind of work we were doing.

The old fashioned record companies had their own sleeve art departments, were very staid in their views and didn’t want young upstarts encroaching on their world – while we were coming along with images like the Pink Floyd cow that had no writing on the front, no explanation, not even the name of the band, and they thought we were extremely disrespectful to the industry… which we were.

But at the same time, we knew that in the world in which we lived this was to be highly regarded. So Storm and I developed all this stuff together, but inevitably rifts and cracks started to appear, which we couldn’t wallpaper over, because we wanted to go different ways – I wanted to do much more of my own thing, and he wanted to plough onwards as we were and keep me back a bit.

Then we found Peter Christopherson by chance: he wandered into our studio looking for a job, and he had an amazing portfolio. He had these great pictures of people, naked figures, very bizarrely angled and posed – little did we know that he’d been working in a mortuary and they were corpses he’d photographed while he’d been there. But he was very good at lighting and good in the darkroom, so we employed him immediately, and thankfully he proved to be a very good balance between Storm and I – so if things got heated, Peter was a sort of bouncing board for both of us.

He was younger, he had a very different outlook to both of us, he was already involved with that very early movement of industrial music – which I think became, or fed into, punk in a way – he acted as a balance between the two of us, and the three of us together were just formidable in design, photography and ideas too.

Peter Gabriel – Peter Gabriel (1977)

Talking of punk – that presented itself as a response to the bloat and self-satisfaction of seventies rock; did you have concerns about this yourself? Did you ever feel that the esoteric, spontaneous excitement of your youth was lost?

Yes. I think this was one of the causes of big rifts between Storm and I actually. He had a saying: “put the art first and the money will come later” – and he was absolutely right. In the beginning I didn’t believe him, but that turned out to be true. As we both grew within Hipgnosis, Storm became more Communist, you might say: he didn’t care about the money, he cared about the work. I wanted the work, I wanted to do good work, but I cared about the money too.

Sometimes Storm was quite happy to do things because he loved them, without getting paid. I generally wasn’t. Although it sounds slight, this difference, it could build up when you were working at the extreme pace we were. The amount that came out of the Hipgnosis studio in those 15 years was phenomenal. It was non-stop 14 hour days, seven days a week, all round the world. The stresses of that, and the difference between us, it nearly caused collapse several times.

We were like brothers – we were like brothers until the day he died last year, in fact. We were very close, but in the same way that siblings fight, so did we. Often I had to resort to violence with Storm, if he was trying to intellectually bamboozle me, by throwing heavy objects across the studio at him. But there were always apologies, we always made up, and there were differences, big differences. Sometimes Storm really was so frustrating I had to resort to extreme violence… in the nicest possible way.

He used to just piss me off sometimes. I did with him too. But sometimes the best relationship is the Jagger-Richards relationship, the Waters-Gilmour relationship, the Page-Plant relationship. All of these have a very powerful dynamic: they’re like brothers, but they fight to the death to get what they want, and Storm and I were no different.

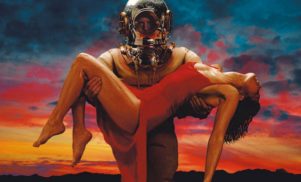

Led Zeppelin – Houses of the Holy (1973)

What about in the present day – do you feel the legacy of those first days in Cambridge is present in pop or underground culture now?

No, I don’t – and I’ll tell you the reason: everything was on a very personal, tactile, hands-on level in the sixties. Nowadays everything is done by social media, through phones, email, Facebook, whatever. And I think to find a group of individuals so locked-in would be quite hard to imagine now, because people behave differently, social mores are not what they were. I’m not saying that’s a bad thing, but it’s different.

I’m sure there are revolutionary groups of creative people around but I just don’t know them. But I do feel that modern technology allows people to be distant from one another and not communicate on a deep, emotional and passionate basis. If you get pissed off with something, you just send a text, you don’t have to wait and confront them face to face and say, “you’re an asshole, I don’t like that photograph you’ve taken”, which you had to do before. I’m not sure, therefore, that the digital world has created a more healthy environment for real passionate emotion to be had between people – but I don’t know. I could be completely speaking out of my arse on this.

But your core message is, essentially, that people should fight more?

Oh, without any question. Without any question, for me, that’s an essential part of the proceedings. I always say to students if I give a lecture that it’s very simple: if you want to get ahead, there’s plenty of places to go, plenty of exciting positions to occupy, and it might as well be you that goes there. Somebody has to be the prime minister, somebody has to be the head of the V&A, somebody has to be Lucien Freud.

It takes a little bit of talent, a little bit of who-you-know, a little bit of being engaged – but far more it takes an tremendous amount of hard work and resilience and ability to fight, physically if necessary, for what you believe. If you can somehow join all those elements together then you can make it.

There are a lot of people out there who are more talented than I am, and more talented than Hipgnosis, but actually the rage with which Storm and I went through life in order to gain ground and gain the upper hand over the establishment to do the work we wanted to do – without that rage, we would never have gone everywhere. Better people fell by the wayside, more talented designers, better individual photographers, but they didn’t have that desire to kill for their beliefs that I think Storm and I had.