For a brief period in the ‘90s, a generation of ravers danced to DJs such as Mr C and Carl Cox in a country house in the south of England. Tom Fenwick tells the story of Sterns, the world’s most unlikely superclub.

It’s said that on a clear morning from Highdown Hill, you can see for miles in every direction across the south coast. Its summit is best reached via a tarmac drive that connects farmland, playing fields and public gardens to the sleepy Sussex parish of Ferring. The climb is steep, and before you reach the peak the road levels out to a clearing, a place to catch your breath in the grounds of an innocuous old house.

It’s recognizably a hotel, but its cropped square towers and jagged flint exterior impose a deeper sense of history. The façade is seemingly torn from the clichéd ‘dark and stormy night’ of a gothic novel and only somewhat softened by an expanse of ivy. But if you could stand here in the same spot on a similarly clear morning in late 1991, the atmosphere would be quite different.

An ocean of muddy Kickers and sweat-drenched bomber jackets surrounds you as close to 1500 ravers emerge from the same stately mansion, blinking and stumbling into reality. A few of them are still wrapped tight in the club’s embrace, refusing to let the party end, dancing around makeshift sound systems that dot the adjoining car park. Vans packed with speakers, jacked up stereos and bass-bins billowing from hatchbacks, “get ill, get ill, get ill in the house on the hill” still ringing in their ears. Others, still too mashed from a handful of snowballs, wallow in the embers of the night. The sun rises across the slopes of the South Downs and a warm glow is cast over the place they call home. A club they called Sterns.

“All too soon acid culture entered the mainstream and everyone was either trying to cash in or catch-up.”

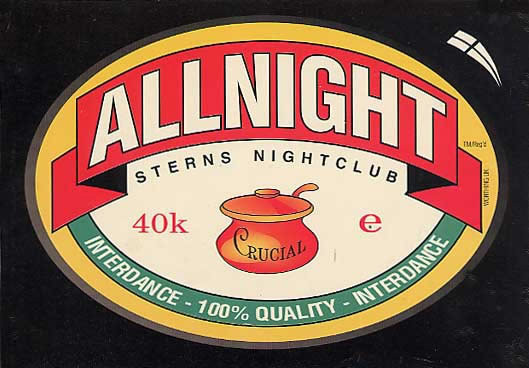

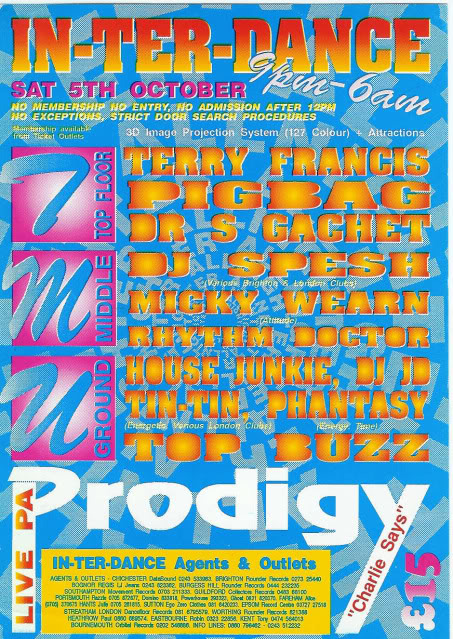

In retrospect it seems ludicrous that one of the UK’s most beloved nightclubs, and the epicentre of rave culture on the south coast, stood at the top of a hill next to some picturesque chalk gardens, just outside the coastal retirement hub of Worthing. But when the lynchpin behind In-Ter-Dance, local promoter Mensa, was approached in the early ‘90s to put on events at Sterns, it felt like he was already light years ahead of his time.

The late ‘80s had already seen the Second Summer of Love hit reset on British youth culture. All-night raves, unlicensed club nights and warehouse parties had spread across the UK, but the scene was a victim of its own success. All too soon acid culture entered the mainstream and everyone was either trying to cash in or catch up; in one notable example, The Sun offered Acid House T-shirts for sale, gave their readers guides to club ‘lingo’ (“Want to speak like the coolest groover on the floor?”) and, in a moment of stunning ignorance, gave them 10 reasons to say “no” to the evils of LSD. But while the police and the media might have been slow on the uptake, once they finally figured out what was going on — and connected it to a perceived rise in drug use and criminality — they cracked down hard on UK rave. Freedom To Party campaigners were taking to the streets of London to protest rigid new legislation, while later in the same year Yorkshire’s ‘Love Decade’ event saw mass arrests; an astonishing 836 in a night on one occasion. And by 1990, a deadlock between authorities, promoters and punters was threatening the entire movement.

In an effort to combat the proliferation of illegal raves on the south coast, the police and council sought to find a mutually acceptable solution that would stop the unlicensed events but also keep the ‘junkies’ out of town centres; somewhere small enough for containment and remote enough to limit people’s access. Sterns was seen as the ideal spot. The mansion, once home to plant collector Sir Frederick Stern, has been through various incarnations since his death: an institute of choreology (a form of dance notation), a failed language school and, since the late ‘70s, an intermittently successful club. The apocryphal story goes that the local council had awarded the licence because it wrongly assumed Highdown to be a ‘country’ club not a ‘night’ club.

“In terms of clubs, Sterns was unique.”

Mr C

Mensa, a local promoter who’d already organized a few events but nothing quite as legitimate as Sterns, was approached to host nights under the banner of In-Ter-Dance. Within six months he’d been granted a permanent 6am licence, which, at least initially, gave him autonomy to run events the way he wanted. It was the summer of 1991, and the result of this ‘long leash’ license was a series of bi-weekly ‘members only’ all-nighters, with an altogether more reserved finish time (3 or 4am) in the intervening weeks.

A melting pot of dance music that spanned multiple genres across multiple rooms, Sterns might seem straightforward by the standards of today’s superclubs, but at the time its setup was unusual. The Top Floor, The Garage and The Underground were the three main rooms, each playing different music with regular sets by big names and up-and-comers alike, from Colin Dale, Ellis Dee and Slipmatt to Carl Cox, John ‘00’ Fleming and The Shamen’s Mr C. Side rooms were set aside as a comfortable chill-out areas (an innovation afforded by Sterns’ unusual layout) well before ravers deemed the concept a necessity.

The first time Mr C played Sterns was notable for a number of reasons, not least because it marked an important milestone in his career as a DJ: the first ‘legal’ all-nighter he played in the UK. And he remembers his time spent there well. “In terms of clubs, Sterns was unique,” he says. “I mean, musically there were similar things happening across the UK and lots of great one-off events along the south coast, but nothing quite on the same scale and certainly not weekly.”

Sterns’ level of diversity was also what set it apart from the rest of the pack, although as Mr C tells it, that could be a blessing and a curse. “Every room had a different crowd and when In-Ter-Dance first took on the place there’d be techno on the main floor and house on the second.” But “cheesier” rave soon took the prime spot, and Mr C remembers how the main room would fill up with a less discerning crowd. “It made the smaller rooms my favorites, because the crowds were older and into proper underground stuff.”

While Sterns may have been a haven of diversity inside, after two years of rampant success — peaking at a membership of 25,000 — cracks in the relationship between the club and the community began to show. Much like the rave scene itself, success had brought Sterns under too much scrutiny. Police raids, drug busts, violent incidents and rumors of underhand behaviour eventually led to a series of licensing wrangles. Initially the club only lost its all-night status, but the knives were out. By the end of 1993 the council removed its license entirely. On August 14 that year, Sterns held one final party, and at 2am the following morning shut its doors forever.

Whether in terms of its innovative license, or as a future blueprint for clubs in the UK, Sterns’ legacy is undeniable. It may not have been the first club on the scene, nor was it the most musically innovative, but for a brief period in time it might have been the most progressive and beloved. Perhaps its ultimate legacy comes directly from Mensa who, as Mr C describes, was “very authentic and had a vision of how society could grow and come together. There were very few people like him in the industry back then.” Mensa’s clubbing concept was an idea that still resonates today: to join people together through acceptance and community.

But it’s bittersweet, as Mensa would never live to expound upon this idea. Six months after Sterns closed he was killed in a car accident. “Mensa was amazing. He was the reason why Sterns worked,” says Mr C. “He was a good man, positive, intelligent and realistic yet rebellious, and one whom I’m very happy to have called a friend.”

Highdown’s unyielding topography may have changed little over the centuries, but every footprint on the face of its hill has shaped history: from Saxon kings, smugglers and knights of the realm, to a visionary promoter, legendary DJs and a vast swathe of clubbers. It’s said that on a clear morning from Highdown Hill, you can see for miles in every direction across the South Coast. For a brief period in the ’90s, a generation of people thought they could see forever.

Tom Fenwick is on Twitter

Read next: Seven nostalgic rave movies that are crying out for a sequel