Like this? You can read FACT’s rundown of the 100 Best Albums of the 1980s here.

Welcome, ladies and gentlemen, to The 100 Best Albums of the 1990s.

We’ve been chewing over this selection for nearly two years now, on and off. It’s not a process into which we’ve entered lightly, but along the way we’ve tried to keep the debate fluid, fun and above all personal. The result is a list that above all reflects our preferences and our prejudices. We’ve sought to include as many personal favourites of our staff members as possible (we’ve also gathered quotes and requested blurbs from some of our favourite contemporary musicians), and above all we’ve done our best to be honest: these are records that we truly love, records that we truly enjoy listening to even now. No false nostalgia, no sacred cows, no going through the motions. Many of the chosen LPs we discovered during the 90s, many we discovered more recently. At the end of the day, this is a list of the best albums of the ’90s from a very precise and peculiar vantage point: 2012. If we had compiled the list last year, or next year, it would look broadly similar to the one you’re looking at now, but certainly not identical. Our perception and understanding of the past is always changing and always, we hope, improving.

And so it begins. Today we’re publishing the first 20 of our 100 (#100-81), and we’ll be publish another 20 each day this week, with #20-1 revealed on Friday. So strap in, prepare to pump your fists in agreement and shake them in outrage, as we lift the lid on FACT’s 100 Best Albums of the 1990s.

100. Lil Wayne

Tha Block Is Hot

(Cash Money, 1999)

In case you missed the memo, Lil Wayne’s more interested in skating than rapping these days, and it explains a lot – bar a few moments on recent-ish mixtape Sorry for the Wait, he’s been one of the laziest stars on the genre’s frontline for quite some time. Either way, if the coming years are to see the dust settle on Weezy’s career, don’t be surprised if 1999’s Tha Block is Hot becomes reevaluated as his best: less drug-addled and spluttered-out than his work in the next decade, it captures Wayne naive, confused and trying to find his way in a cold world – several tracks (‘Fuck tha World’, ‘Up to Me’) are moving tributes to his murdered stepfather, while on others (‘Kisha’, ‘Loud Pipes’), he spars with his Cash Money contemporaries like the best Hot Boys cuts.

99. Painkiller

Buried Secrets

(Toy’S Factory / Earache, 1992)

More atmospheric and less silly than debut EP Guts of a Virgin, the second transmission from Painkiller (John Zorn, Mick ‘Scorn’ Harris and Bill Laswell) showcases some of the decade’s most confrontational characters at close to their peak: whereas Zorn, in particular, can tire over the course of a whole album, here the balance between endlessly echoed doom, squealing murder-skronk and lo-fi grind works perfectly. Godflesh’s Justin Broadrick and G.C. Green even join the party at points, making Buried Secrets as close to a jolly as grindcore ever got.

98. The Olivia Tremor Control

…Dusk At Cubist Castle

(Blue Rose / Flydaddy, 1996)

The neglected little brother to Neutral Milk Hotel’s In the Aeroplane Over the Sea, the first album from Georgia’s The Olivia Tremor Control – which sounds roughly like the Beach Boys dissolved into clouds – remains an overlooked piece of the ’90s indie puzzle. Sadly, the recent death of founding member Bill Doss was the first time we’d heard people mention the group in years.

97. Codeine

Frigid Stars

(Glitterhouse / Sub Pop, 1990)

Released right at the start of the decade, and a clear influence on Mogwai and others, what’s still remarkable about Frigid Stars is how classic it sounds from your very first listen. None of its songs have had the advantage of being buried into the trans-Atlantic subconscience the way that the most recognisable tracks by Pixies or even Pavement have, yet from that first guitar lick, the first time “D for effort…” leaves Stephen Immerwahr’s mouth, you feel like you’re listening to an album that you know each note of. It’s no coincidence that Frigid Stars features a track titled ‘Gravel Bed’: this is music that ebbs and flows like the tide on the coast, but with a bitter, bored core that’s far spikier than mere sand.

96. Source Direct

Exorcise The Demons

(Science / Virgin, 1999)

Jim Baker and Phil Aslett’s extraordinary run of 12″s singles released between 1994 and 1998 – on Good Looking, Certificate 18, Metalheadz, Odysee and their own Source Direct Recordings – established them as one of drum ‘n bass’s most talented and dark-hearted production units. By the time their major label debut album, Exorcise The Demons, arrived, their best days were already behind them; this was an album boasting all the precision-engineered brutality of their previous work, but lacking its beauty, and its humanity. It remains nonetheless a thrilling document of smacked-out, misanthropic jungle for stalkers, serial killers and ne’er-do-wells – no wonder opening track ‘Call & Response’ is the favoured listening of Stephen Dorff’s vampire villain in Blade.

Logos (Keysound): “Source Direct will always be, for me, the masters; a weaponised hybrid of The Parallax View, hardcore rave and the breakbeat. Exorcise the Demons is the flawed, at times frustrating but still essential culmination of their mid-90s experiments.”

95. Scott Walker

Tilt

(Fontana, 1995)

Scott Walker’s journey is a pretty unique one: from ’60s teen heartthrob to avant-garde visionary, via a decade or so of Valium-addled MOR decrepitude. 1983’s Climate Of Hunter marked the singer’s return from obscurity, but it’s the 1995 follow-up, Tilt , that really sees him hit his stride. Walker’s lyrics verge on impenetrably dense, pivoting lithely between the starkly personal and the cryptically political, and the arrangements follow suit: from the industrial clatterings of ‘The Cockfighter’ to the threateningly sparse ‘Bolivia ’95’, Walker sculpts sounds that explore the outer limits of the orchestral palette, as well as twisting pop forms into tortured, exquisite new shapes.

Joakim: “Crooners can be assholes in real life and angels when they sing. They can save your soul, they are super-humans.”

94. Reload

A Collection Of Short Stories

(Infonet, 1993)

Before Global Communication really become a going concern, Messrs Pritchard and Middleton dreamt up this sprawling dreamtime techno opus, complete with ambient interludes, industrial hissy fits, dusty breakbeats and a booklet of cosmic pulp fiction to boot.

93. Company Flow

Funcrusher Plus

(Rawkus, 1997)

Airlock jams and soapbox proselytizing from Brooklyn’s nimblest operators. There were tougher and tricksier rap records, but few had Funcrusher Plus’s furious panache.

El-P: “It was different back then: We were in The Source, DJ Premier was rocking our shit on his mixtapes, KRS-One was rapping above our instrumentals. We kind of came out at the perfect time because people hadn’t yet created subgenres so we were thrown into the pantheon of rap music in general. There wasn’t a lot of people being like, ‘Wow, they listen to this kind of rap.’ But when I was a kid I just assumed everyone should like this shit because I felt like I was the ultimate hip-hop fan. Like: ‘Yo, this adheres to my very fucking strict standards of what a dope record should be.’ I was 21 so I was pretty fucking high on myself.”

92. Erykah Badu

Baduizm

(Universal, 1997)

If D’Angelo’s 1995 album Brown Sugar fired the starting gun on what came to be termed Neo-Soul, then Baduizm, released in 1997, was the so-called movement’s early peak. Compared to the sprawling, symphonic and increasingly auteurish ambitions present in Erykah Badu’s later work, her debut album feels lightweight – but its streamlined, unfailingly smooth exterior conceals a sharply observed lyrical core. From quietly heart-rending socio-political commentary (the exquisite ‘Otherside Of The Game’) to naked expressions of desire (‘Next Lifetime’) and easy humour (the improvised ‘Afro’) Baduizm succeeded in smuggling subtle, challenging and at times troubling emotional content into the dinner parties and hotel lobbies of the Western world – all under cover of a silkily urbane, endlessly gratifying boom clack.

91. Arab Strap

Philophobia

(Chemikal Underground/Matador, 1998)

It’s hard to talk about Arab Strap without falling into cliche, or even sounding condescending: yes, on the surface it’s depressing music about depressing subjects played by depressed-sounding Scots, but to focus on that would be to do Aidan Moffat and Malcolm Middleton several disservices. Firstly, for a pair of miserable c**ts they pen a euphoric climax better than most trance producers (Tiesto’s never written anything as soaring as the close of ‘There is No Ending’ or ‘The First Big Weekend’), and secondly, unlike many of their contemporaries, Arab Strap never moped – each tale of desolation or disgrace was delivered with a knowing smile and sense of perspective. It’s been said before, but who else could write a song as heart-breaking as Philophobia‘s ‘Packs of Three’ and open it with that line?

90. Bratmobile

Pottymouth

(Kill Rock Stars, 1993)

Bratmobile: the definition of three-chord amateur punk, with lyrics straight out of a high school diary (“I don’t wanna hear how many friends you have / I don’t have any anymore”), but by God did it work, and just how ridiculously welcome would it be now? ‘Polaroid Baby’ (“Polaroid girl / Polaroid boy / You’re so white and you’re so cute / Burn to the fucking ground L.A.”) sounds directed straight at the Instagram generation, while ‘Fuck Yr Fans’ is the sort of declaration of unadulterated hate that indie rock’s barely had the chutzpah to show in years.

89. T-Power

The Self Evident Truth Of An Intuitive Mind

(Sour, 1995)

Sumptuous drum ‘n bass science fiction – a trip to the dark side of the moon powered by pistoning Amen breaks and sighing, widescreen string pads. Self Evident Truth came out the same year as the far more fauned-over Timeless, but while Goldie’s debut looked to slick jazz-funk and soul for off-piste inspiration, T-Power’s creation felt more aligned with the Detroit techno of the early ’90s – if Carl Craig was a junglist, he might have made something like the sublime ‘Circle’.

88. Spell

Seasons In The Sun

(Mute, 1993)

A collaboration between controversy-bating noise terrorist Boyd Rice (NON) and goth pin-up Rose McDowall (Strawberry Switchblade), Seasons In The Sun is a surprisingly sweet, faithful covers album of rock ‘n roll, teen-pop and country songs from the 1950s through to the ’70s – or at least so it seems. Under the wry, breezy, Nancy’n’Lee-ish exterior lurk demons and mischief: lyrics are modified to sound darker and more fatalistic, references to Hell and death are introduced. There is poison in this cherry pie. The biggest surprise, though, is Boyd’s voice: an oaky croon of uncommon warmth and gravitas.

87. Felix Kubin

Filmmusik

(Gagarin, 1998)

Filmmusik is the sort of capriccio the forward slash was made for: an album/OST/radio show/scrapbook/verbatim piece/dream journal that offers unprecedented insight into the German artist’s cluttered mind.

Felix Kubin: “All I know about Felix Kubin personally is that he claims to have telepathic connections to outer space intelligence, especially to Jurij Gagarin and his humming protones…Felix is also fascinated by eerie sounds, he started to use them in his compositions when his mother died. I wouldn’t want to share a room with him but I respect his music. Concerning music he is ‘ok’, I think.”

86. Porter Ricks

Biokinetics

(Chain Reaction, 1996)

Serous art-techno from Thomas Köner and Andy Mellwig’s groundbreaking production project, calibrated for the dancefloors but perfect for the floatation chamber.

Thomas Köner (Porter Ricks): “Do I have to be remembered at all? Can’t I just disappear?”

85. E-Dancer

Heavenly

(Planet E, 1998)

A collection of tracks made by Kevin Saunderson under his E-Dancer moniker, including remixes by Juan Atkins, D-Wynn, Kenny Larkin and Carl Craig that fit seamlessly into the flow of future-rushing, maximalist machine-funk. You won’t find a better one-shot demonstration of mid-’90s Detroit techno’s soul, vision and studio invention.

Kevin Saunderson (E-Dancer): “The most important part for me is creating a sound that is unique. Getting within the parameters and the oscillators, you know, I like that kinda shit, create magic. Most people don’t know that, there’s a bunch of new kids, they just look for presets.”

84. Mr. Bungle

California

(Warner Bros, 1999)

California: aka what happens when Mike Patton’s original band – not quite his weirdest one, but certainly not his poppiest, either – decide they’re going to… you know what, scrap that. I doubt anybody, even Mr. Bungle themselves, quite knew what they were aiming for with California, bar some loose idea of making a “pop” record, but it emerged as a bona fide classic. Hotel lobby piano, doo-wop style harmonies, vaudeville swing, rockabilly and surf-pop so laid back that it bought the hammock before the beach house all feature, and somehow all find space to breathe on a mine-cart ride full of violent twists, sudden gear shifts and more. On ‘Retrovertigo’, the group aim skywards with a Vanilla Sky-daubed ballad every bit as potent as Radiohead’s best moments, while ‘The Air Conditioned Nightmare’ is what Quentin Tarantino’s head must sound like when he hasn’t slept for days. ‘Vanity Fair’, meanwhile, sounds like it should be soundtracking a wedding, until you’re realise that it’s roughly about circumcision. California then: how to cram 1000 genres into one record, and make it work. Girl Talk, take note.

83. Carlton

The Call Is Strong

(Ffrr, 1990)

Summery, silky-smooth but rave-savvy Bristol soul from the man who vocalled Massive Attack’s debut 12″, brought to life by perfectly rugged production from Smith & Mighty. Despite its all-but-forgotten, bargain bin status today, this record has stood the test of time a lot better than Soul II Soul’s similarly oriented Club Classics Vol.1. It’s a lost classic, make no mistake, and quite how it got so lost – especially given its clear abundance of pop and club appeal – is an absolute mystery.

82. Beastie Boys

Ill Communication

(Grand Royal Records, 1994)

In the Beasties’ Homeric odyssey of self-definition, Ill Communication remains the port where they sounded most comfortable. Snotty, funky and screwy, it showed these unlikely journeymen at the peak of their game.

81. Photek

Modus Operandi

(Science/Virgin, 1997)

Jungle noir – moody, minimalist, sophisticated and tough. In the end, Modus Operandi is perhaps a little too cool, a little too painstakingly constructed, for its own good – it’s an easier album to admire than to love. But really, who could fail to be seduced by the icy rollage of ‘Minotaur’ and ‘Trans 7’, the interstellar funk of ‘Aleph 1’, the deep blue techno of ‘124’, or the smoked-out future-jazz of ‘KJZ’ and the title track? It’s hard to an imagine a dance music album so conceptually robust and vividly, exquisitely produced being made today, let alone coming out via a major label.

Photek: “I feel like there was definitely a concept behind it…but I’m not sure how well I could articulate it, even now. I mean, that’s how the title, Modus Operandi, came about in the first place: back then so many different people, in interviews or whatever, were asking me to define jungle. The way I chose to define it to them was as a style of programming, a style of using sonics to make music, as opposed to using instruments to make music. This was music purely about soundscapes, space, bass…and you can forget how hard this was to explain to some people at the time. And at the same time, it was quite open: I felt like any style or tempo of music could fit on Modus Operandi if it was sonically right.”

80. Cows

Cunning Stunts

(Amphetamine Reptile, 1992)

The best album from the Midwest’s finest blues-rock bastards, we could talk all day about Cunning Stunts, but its Wikipedia entry – which doesn’t seem to have been updated since the 1990s – is unbeatable in its simplicity: “The first album where [Cows] began developing real melodies and patterns instead of their usual blasts of noise. It is no longer in print; however, it is available online at wmp.emusic.com, on Windows Media Player 10 and on iTunes.”

79: Biosphere

Substrata

(Origo Sound, 1997)

The notion of “glacial” ambient music is a monstrous cliche these days, but it wouldn’t exist were it not for Geir Jenssen’s magnificent Substrata, an album whose drifting Arctic serenity gives new meaning to the phrase “chill out”. ‘Hyperborea’ samples dialogue from Twin Peaks, specifically Major Briggs’ moving recollection of his dream to his son, Bobby, and this speech serves also to describe the experience of hearing Substrata for the first time: “This was a vision, fresh and clear as a mountain stream, the mind revealing itself to itself. In my vision, I was on the veranda of a vast estate, a palazzo of some fantastic proportion. There seemed to emanate from it a light from within, this gleaming, radiant marble. I’d known this place. I had in fact been born and raised there. This was my first return. A reunion with the deepest well-springs of my being.”

78. Above The Law

Black Mafia Life

(Ruthless, 1993)

Released after Dr. Dre halted his involvement in the group (he executive produced Above the Law’s Livin’ Like Hustlers; the group’s producer Cold187um later claimed to have pioneered the twisted G-Funk style that Dre made famous on The Chronic, released prior to this album but actually recorded after it), Black Mafia Life showcases the West’s great nearly-men. The production bears all the G-Funk hallmarks, but comes put together in a rough, collaged style, too loose for the charts, while the samples are just that little bit too obvious at times – let’s face it, for all Dre’s faults, you couldn’t see him sampling Hall and Oates’ ‘I Can’t Go For That’ in 1992*. The rapping, meanwhile, is again loose and scattershot; for all Above the Law’s qualities, it’s clear in retrospect that they didn’t quite have the ear for a radio-friendly hook that made Dre a star. Still, footnotes rarely sound as good as Black Mafia Life.

*Yes, we know De La did.

77. Godspeed You! Black Emperor

F# A# ∞

(Constellation, 1998)

We mused on the idea of including Godspeed’s oft-overlooked 1999 EP Slow Riot for New Zero Kanada in this list, still the tightest, all-killer-no-filler record that the Canadian anti-rock group ever made, but it seemed to miss the point. The reason Godspeed’s music works so well over the course of a full-length album – on both this, and 2000’s Lift Yr. Skinny Fists like Antennas to Heaven – is because it needs time to meander, to retreat, dust itself off and come back at you with double the force. Sure, there are stretches of F# A# ∞ that are forgettable, but that’s just the way that Godspeed move, and this record, for us, captures them at their effortlessly iconic best.

Jacques Greene: “Godspeed You! Black Emperor have always had this sort of looming presence in my neighbourhood in Montreal. Though they were more or less over by the time I was going to shows, their ‘legacy’ or whatever you’d want to call it lived through studios and bars they had opened and their continued involvement in other bands. I came across their music through a friend in high school and proceeded to learn so much from all their records about pace, sound, the sense for restraint, but to also know when it’s time to go big and dense.”

76. Moodymann

Silentintroduction

(Planet E, 1997)

A history lesson in more ways than one, singles collection Silentintroduction plots Kenny Dixon Jr.’s fledgling steps, and simultaneously concertinas half a century of black music into ten stunning pieces of nuclear Afro-fusion.

Carl Craig: “The talking, the narration that caused so much controversy – all that. That was the first time that I ever dealt with anything that had all that controversy. He made some statements – Detroit militant statements – that were more him being silly than anything that he ever believed. Of course, it always seems like when it comes down to race, that it’s a one-sided story with a lot of folks, and I think people got that kind of concept from it. But he’s not that kind of guy.”

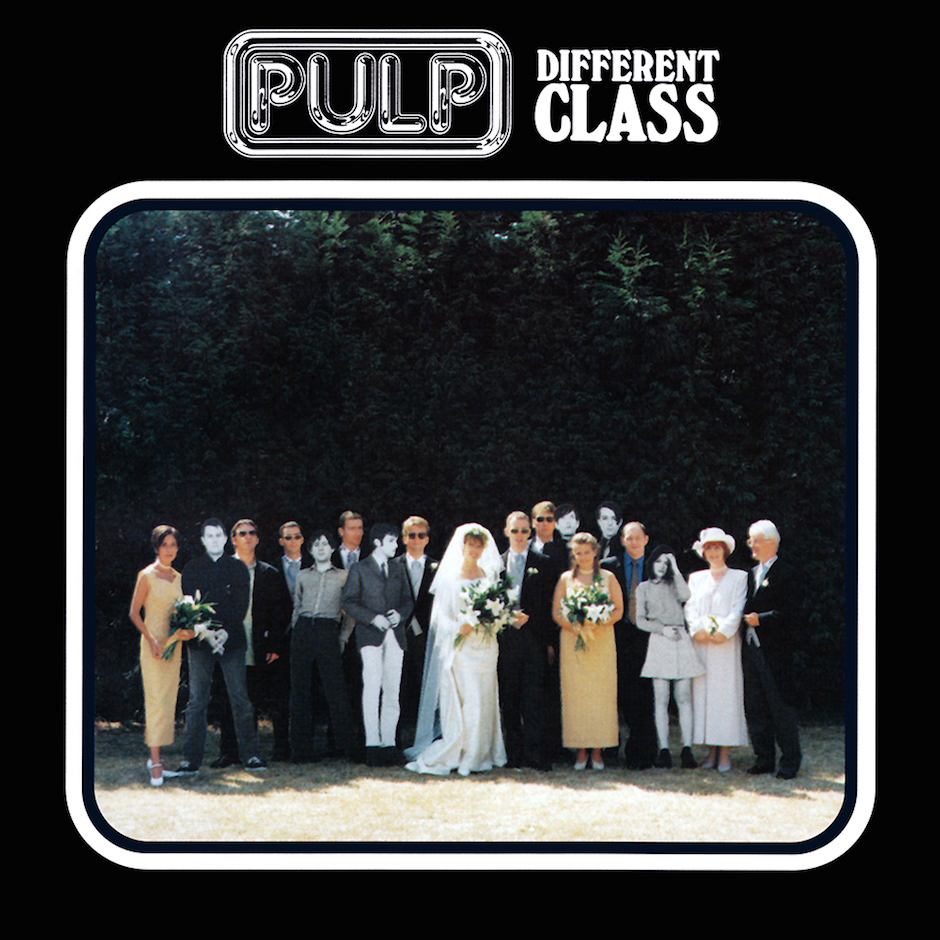

75. Pulp

Different Class

(Island, 1995)

Right – the comments section is right there, does anybody have a bad word to say about Pulp? The best band to ever be associated with Britpop (though unlike many of their supposed peers, the Sheffield group both predated its rise and comfortably survived its downfall), Different Class is a blindingly obvious pick for a list like this, but there’s a reason for that – it is, simply put, from start to finish, just an unbeatable record. Forget ‘Common People’ and ‘Disco 2000’, because the chart-topping singles aren’t even half of the Different Class story; instead, throw on ‘Something Changed’ and remind yourself of arguably the best love song a band from England wrote all decade, or the gently tumbling ‘Underwear’, all torn-open desires and shared moments of bliss over damp patches. Meanwhile, on closer ‘Bar Italia’, Pulp captured the faded morning after the rave just as well as later musicians who’d specialise in it (Burial, The Weeknd), and did it so casually it hurts.

74. DäLek

Negro Necro Nekros

(Gern Blandsten, 1998)

The debut transmission from New Jersey’s pre-eminent signal jammers, and a bracing introduction to their heavy-browed amalgam of shoegaze, noise, drone and thug-rap.

73. Herbert

100Lbs

(Phono, 1996)

Given the cerebral shenanigans that have defined Herbert’s last decade, 100lbs remains an astonishingly physical, exquisitely rendered house record – for all the pig-sampling high jinks, he’s yet to top it.

Matthew Herbert: “I started playing violin and piano at the age of four, and I was in a big band when I was 14. So I think conversely my music teachers would probably have listened to 100lbs and been quite confused. That formal technique of music and harmony had been something I’d been learning for many years. The electronic stuff was much more surprising to me. It was kind of a reaction to all that learning. I spent a lot of time learning that if you played a wrong note you were a bad musician, and that didn’t seem to correspond to how I felt music was in my own life. When music technology was democratized in the ’80s it allowed me to develop my own style and ideas at home, away from church halls and other people.”

72. Unwound

Fake Train

(Kill Rock Stars, 1993)

Forget Refused and Fugazi, Unwound’s Fake Train is the true pinnacle of intelligent, prolix but still furious post-hardcore punk, with way more swagger to boot. Best sleeve art ever too: a crudely defaced version of the cover from Tom Jones’ 1977 LP, Tom.

Aaron Warren (Black Dice): “I listened to this record every day the year it came out, and for quite a few years to come. This band was the very model of success to me, making records every year, touring, playing DIY shows, living the independent dream to the max. The music on here is much more angular and dissonant than I remember it being, but it’s basically the meeting of west coast underground rock and the jazzy ideas of dudes like Sun Ra and Ornette Coleman, at least to my ears today.”

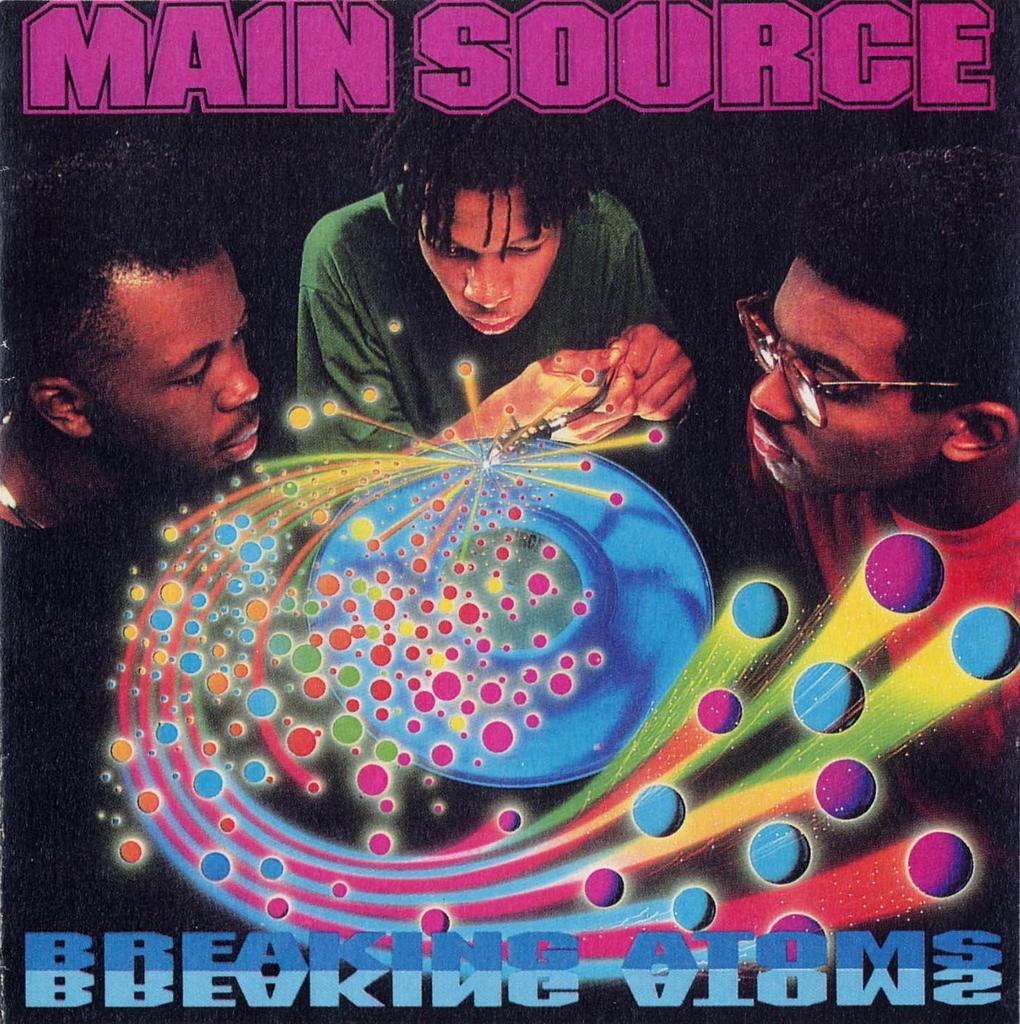

71. Main Source

Breaking Atoms

(Wild Pitch / Emi)

Breaking Atoms sounded hugely ahead of its time in ’91, and was the record that cemented Large Professor as a go-to producer for the next decade in hip-hop. Pro had already helped out on a couple of seminal albums, finishing off the Eric B and Rakim masterpiece Let The Rhythm Hit Em in lieu of the sadly departed Paul C, and working with Kool G Rap and Polo at the heights of their combined genius, but it was with Main Source that he nailed his boom-bap signature and kaleidoscopic sample palette. ‘Looking Out The Front Door’ became an instant and enduring club favourite, thanks to the key-cycling loop of Donald Byrd’s ‘Think Twice’, which went on to inspire revisits by Carl Craig and J Dilla among others. Meanwhile a fledgling rapper named Nas made his conspicuous debut on ‘Live At The BBQ’, and a new chapter in hip hop history began. Confusingly, their best track, ‘Atom’, never made it onto the album and can only be found on the promo 12”.

70. Coil

Musick To Play In The Dark

(Chalice, 1999)

Music To Play In The Dark (issued as a limited vinyl edition in ’99 ahead of full release in 2000) is one of Coil’s most enchanting and accessible records, but it’s still bleak as hell: a sort of serotonin-depleted postscript to their earlier acid house phase. ‘Are You Shivering?’ was supposedly conceived as a paean to the magickal effects of MDMA, but clearly it’s concerned more with the comedown than the high, in particular that moment when night gives way to morning and one feels, in Jhon Balance’s beautifully chosen words, “squidlike and squalid”. ‘Red Birds Fly Out Of The East And Destroy Paris In A Night’ reimagines Detroit techno as part of the European gothic tradition, while the sepulchral cabaret jazz (!) of ‘Red Queen’ channels Isherwood via Marc & The Mambas. R.I.P. Jhon and Sleazy – the world is a far less interesting place without you in it.

Surgeon: “I like the fact that they lived the life of their music. Gives it more gravity, greater depth.”

69. Michael Head & The Strands

The Magical World Of The Strands

(Megaphone Music, 1997)

In 1997 life was pretty shit for Michael and John Head, the Liverpudlian brothers behind The Pale Fountains and Shack. Their studio had burned down, destroying all traces of the nearly-completed new Shack album with it (the one back-up tape in existence was accidentally left in an American rental car by their manager, and never recovered). They were skint. Oh, and they were in the grip of heroin addiction. Given the circumstances, one might have expected their next creative move to be suicide, but thankfully for them, and for us, Mick Head looked inside his soul and pulled out the strongest set of songs of his career. Not bleak or self-pitying songs, but hopeful, beautiful, often heart-bursting ones, with lyrics equally preoccupied with the mystical and the mundane, and recorded in a pastoral, delicately psychedelic folk-rock style – all guitar, strings, woodwind and brushed drums – that nodded to their heroes Love, Nick Drake and The Byrds.

Credited to Michael Head & The Strands it was, and remains, a near-perfect record, but in true Head fashion it took two years to come out and at first was only available as an import, attracting critical acclaim but not much else. Soon after its release, Shack got another shot at commercial success – Mick appeared on the cover of NME, hailed by the paper as Britain’s Greatest Songwriter, and they signed to London Records – but the album they delivered, the bloated, over-keen and distinctly embarrassing HMS Fable, wasn’t fit to lick The Magical World Of The Strands‘ boots, and duly flopped.

Michael Head: “It’s that old chestnut – Magical was a smack album, and that’s about the size of it. And that answers a lot of questions, about transformation, and why this, how come that… Finish with smack, Shack make another album. The Strands was me, John, a girl called Michelle on bass, a flautist called Les, and lain on drums. And then it all happened the way it probably should have, they just dissolved away.”

68. Jay-Z

Reasonable Doubt

(Roc-A-Fella, 1996)

What more needs to be said about this record? Released later than many of the New York classics on this list, Reasonable Doubt made up for lost time with a perfect musical equivalent to the Big Apple portrayed by Martin Scorcese and in Leone’s Once Upon A Time in America, every drum hit clouded by cigar smoke, each camera-shot snaking through ominous corridors of unspoken power.

67. Vainio / VäIsäNen / Vega

Endless

(Blast First, 1998)

This alarmingly underrated full-length collaboration between Pan Sonic’s Mika Vainio and Ilpo Väisänen and Suicide’s Alan Vega comes over like the soundtrack to the greatest cyberpunk movie never made. Vega’s cracked-Elvis howl ‘n croon has never sounded so feral and dissolute, and the Finnish contingent produce some of the most varied and vital music of their career, spanning supple, red-light-district techno, twisted steel industrial and even Tangerine Dream-ish synth-scaping. Irreproachably badass.

66. Kyuss

Kyuss (Welcome To Sky Valley)

(Elektra, 1994)

Recorded after Nick Oliveri left the group, and the last Kyuss album to feature Brant Bjork, Welcome to Sky Valley captures the desert rock titans in a minor state of flux, but remains their best full-length. Bjork, for all the alleged disagreements with frontman Josh Homme that fuelled his departure, is an absolute machine on the drums here, and it’s that endlessly rolling percussion that drives Sky Valley, even more so than the sun-scorched guitar that became Kyuss’s trademark. For a record made of such dry sounds, Sky Valley is remarkably slippery in its movements, and, from opener ‘Gardenia’ to its majestic closer ‘Whitewater’, never once toils or tries.

65. Philip Jeck

Surf

(Touch, 1998)

Picking up where Schaeffer and Tenney left off, the turntable artist sits back and lets his choir of phonographs and knackered belt-drives sing. The results are, in more ways than one, quietly revolutionary.

BJ Nilsen: “1998: In the middle of Clicks and Cuts and all that stuff, Surf was the record to really draw my attention. Unlike some of the other turntablists I had heard, he allowed the compositions to take form (or not) organically over longer periods of time, creating warm, ghostly and fragile compositions, the sound of a melted stack of vinyl…The record inspired finalising my debut on Ash International that came out the following year – especially the opening chord of ‘Demolition’, which I ripped off by hitting my guitar at the top of the neck…Hats off to Jeck!”

64. Godflesh

Pure

(Earache, 1992)

Not quite the towering smackdown of urban Britain that 1989’s Streetcleaner was, Pure nonetheless finds Godflesh on fine form – and more musical to boot. The appearance of Loop and Main’s Robert Hampson on four tracks probably helps – whisper it quietly, but ‘I Wasn’t Born to Follow’ is actually quite pretty, with more than a hint of Justin Broadrick’s later work as Jesu to it, while ‘Don’t Bring Me Flowers’ sports echoes of Slowdive. Still, Pure is far from the sound of Broadrick and Green going soft: one listen to the rampaging drum machines of its title track on a proper stereo is unforgiving proof of that.

Justin Broadrick (Godflesh): “We were seen as total outsiders, but managed to get a lot of attention because of it, I think. We were one of those bands that stepped outside the comfortable sense of normality that metal had. You’d rarely see a band in a magazine like that with a guy with shaved head, sitting on the floor and messing with a delay pedal. We were seen as a freakish thing I guess, but there was a comfort in that.”

63. Surgeon

Force + Form

(Tresor, 1999)

Communications (1996) was the record that booted the door in, but Antony Child’s 1999 LP of gnostically-attuned knuckleduster techno is the pick of his sterling album-a-year run through the second half of the decade. Conceived with British agitators like Coil and Whitehouse in mind, it’s brisk, brutal and – on the almost Metalheadz-friendly ‘At The Heart Of It All’, at least – breezy.

62. Westside Connection

Bow Down

(Lench Mob / Priority, 1996)

Hands on hearts, we’d take Westside Connection’s debut album over any of Ice Cube’s solo records. Yes, the combination of Cube and the Bomb Squad provided an unmistakable rush on AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, but to our ears there’s no backing that suits Cube better than casual West Coast bump. The production on Bow Down hasn’t aged a lick since the ’90s – those fat-bottomed one-finger baselines so refreshing in a climate of ultra-compressed 808s, the crackled intro on ‘The Gangsta, The Killa and the Dope Dealer’ still as ominous as ever – and there’s not a single track here that’s close to a turkey. Pledge allegiance.

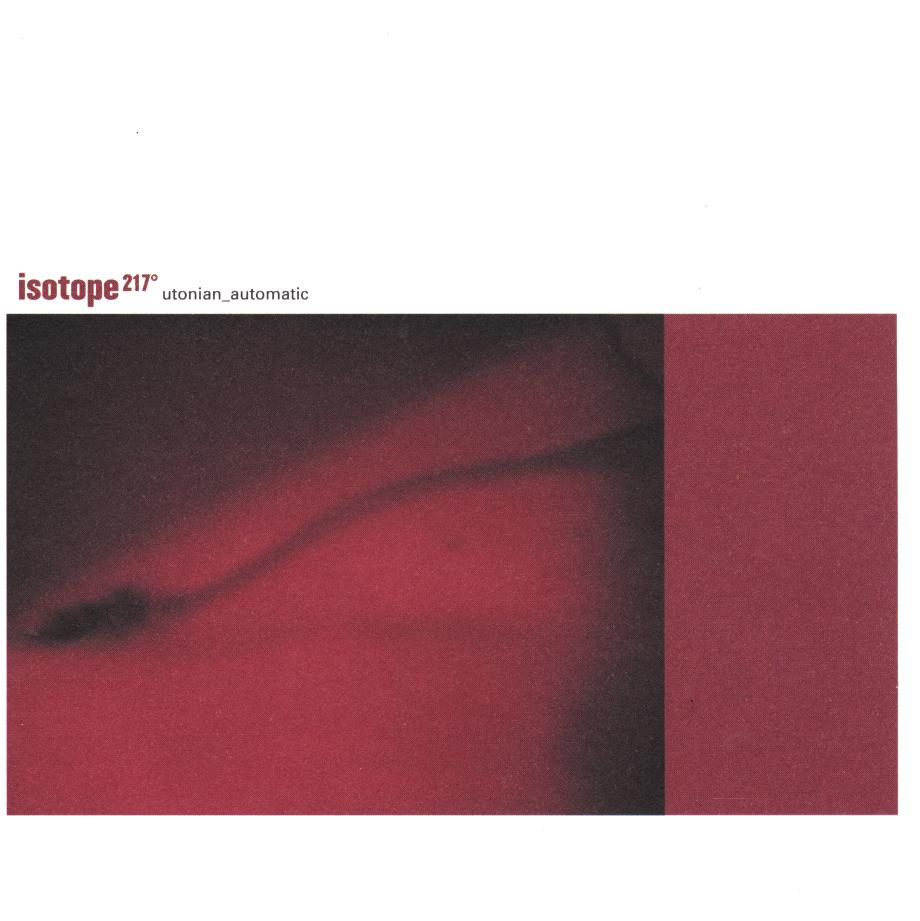

61. Isotope 217°

Utonian_Automatic

(Thrill Jockey, 1997)

Members of the Tortoise/Chicago Undergound Orchestra diaspora free-associate at will; the results (folksy funk; Spaghetti Western trip-hop; Geiger counter jazz) out-funk the former and out-freak the latter.

60. Krust

Genetic Manipulation

(Full Cycle, 1997)

A member of the Roni Size-helmed Reprazent collective that would take drum ‘n bass to Mercury Prize-winning heights with 1997’s New Forms, Krust was a consummate producer in his own right, helping define the sound of spry, rolling Bristol jungle with his numerous productions on Full Cycle and V. 1999’s debut album proper, Coded Language, overstretched itself creatively; far more satisfying is the grittier, club-focussed double-pack, Genetic Manipulation, which preceded it by two years.

Peverelist: “Epic, sprawling visions of the future from Krust. Releases like this, ‘Future Unknown’ and ‘True Stories’ don’t seem to fit in anywhere within drum & bass, and seem extraordinary in retrospect. Krust is definitely the most avant-garde of the Bristol producers.”

59. Spiritualized

Ladies And Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space

(Dedicated, 1997)

“Love in the middle of the afternoon; just me, my spike in my arm and my spoon…” Jason Pierce conjured a work of astonishing, redemptive beauty out of dope addiction and heartbreak, aided by a string section, horns, BJ Cole, Dr John, the London Community Gospel Choir – everything, indeed, but the kitchen sink. Given the long list of contributing personnel, Ladies And Gentlemen still sounds and feels like a very personal offering from Pierce, and this is testament to the singularity and tenacity of his vision.

58. Pole

Cd 1

(Kiff Sm / Pias Germany, 1998)

Germany’s Stefan Betke was so in love with the “crackle” generated by his Waldorf 4-Pole analogue filter, he built his entire creative identity around it. Allied to abstract dub rhythms, it made for a peculiarly haunting form of electronic head music, and you can detect the influence of CD1 and its two sequels – conscious or otherwise – on the likes of Actress, Burial, Andy Stott and The Caretaker.

Pole: “We are talking about attention to detail as opposed to superficial qualities. I spend a lot of my time reducing structural clutter in a song, step by step, layer after layer, until I reach a certain foundation of lasting value.”

57. Belle & Sebastian

Tigermilk

(Electric Honey Records, 1996)

Given the absolute ubiquity of twee bedsit indie in the post-C86 years, it’s funny to think how marginalised it had become by the mid-90s, with macho grunge and laddish Britpop ruling mainstream airwaves and record-racks. Belle & Sebastian’s Tigermilk changed all that, or at least complicated the issue: recorded as part of his final assessment on a college music course, it found whey-faced newcomer Stuart Murdoch ripping off the singing (and frankly songwriting) style of Momus circa The Poison Boyfriend and running with it, adding some chamber-pop flourishes a la Scott Walker and Nick Drake, and serving it up with a generous extra helping of Sarah Records-style wetness. It wasn’t long before a palpable smugness crept into Murdoch’s lyrics, and the parochial romanticism that was B&S’s stock in trade began to sound insincere, but this – this is a masterpiece.

56. Sleep

Jerusalem

(Bootleg, 1998)

In 1996, having landed a deal, somewhat improbably, with London Records, pot-addled, low-end-obsessed doom-metallists Sleep proceeded to deliver not an album so much as one long song: ‘Jerusalem’. The label balked at the idea of releasing it, and, fed up with waiting for them to change their mind, Sleep gave their blessing to a bootleg version of the record, which emerged in 1998, and quickly became a cult classic. An edited version was released a year later on Rise Above / Music Cartel, but it wasn’t until 2003 that the record, rechristened Dopesmoker, finally came out officially in all its unabridged, time-distorting glory.

Julian Cope: “When my all-smiling, all-visionary, all-grimming partner in sonic grime Stephen O’Malley sent me this Sleep album, I immediately thought it was the most ground-breaking record in years because it took an essentially unmeditational musical form (i.e. early Black Sabbath) and sacralised it into the highest form of barbarian sonic code you could ever wish to trip out to. It monged my senses within the first five minutes, then set about my inner structures with sheer weight of adamant repetition and monotony…You could chew up some of the good hash and neck a few beers and lie in bed and sleep to it, leave your body to it, probably even shag to it – though I was too busy to set up such an experiment.”

55. Dopplereffekt

Gesamtkunstwerk

(International Deejay Gigolo Records, 1999)

So here’s how the story goes: Gerald Donald, erstwhile member of Drexciya, borrowed DJ Hell’s BMW and, due to some negligence on his part, managed to write it off. To pay off his debt, Donald gave Hell the rights to put out this compilation of tracks by Dopplereffekt, the project he’d formed to explore a style of Kraftwerkian electro as mercilessly arid as Drexciya’s had been aquatic, all bound up with the imagery and language of eugenics, fascism and sexual objectification. Whether or not the story is true, there’s no doubting the brilliance of Gesamtkunstwerk, an album whose only crime is that it unwittingly helped give rise to electroclash.

54. The Moles

Untune The Sky

(Flying Nun, 1999)

Like their animal namesake, The Moles are destined to remain an underground concern; a shame, really, because their leader Richard Davies (who later formed the similarly obscure Cardinal) deserves to be hailed as one of the finest songwriters of his generation. Originally released in 1991, full-length debut Untune The Sky is a natural expansion of the NZ psych-pop sound established by Flying Nun’s bands in the late ’80s, and Flying Nun in fact released the definitive CD edition of the album in ’99, adding crucial singles and B-sides like ‘This Is A Happy Garden’ and ‘Lonely Hearts Get What They Deserve’. We’d advise you to hunt down that version, or Kill Shaman’s 2010 double-vinyl reissue, if you want to get the full measure of The Moles.

53. Robert Hood

Minimal Nation

(Axis, 1994)

A million miles from what would come to be known as “minimal” in the following decade, Robert Hood took the Detroit techno sound and stripped everything extraneous away, exposing the music’s gleaming, steely endoskeleton. For Hood, 1994’s Minimal Nation was a protest record: “Nobody seems to get that,” he would later reflect. “Techno was becoming one huge sample and the raves were becoming all about drugs…Minimalism is not going to stop, because it’s a direct reflection of the way the world is going. We’re stripping down and realising that we need to focus on what’s essential in our lives.”

Robert Hood: “I was fooling around with a Juno 2 keyboard and I came across this chord sound; once I had that chord sound and a particular pattern I realised I didn’t need anything else. In order to maximise the feeling of the music, sometimes we have to subtract.”

The Village Orchestra: “‘Minimal’ as a term has been used to refer to sparseness of motion, of limited content, of a soporific low key tumble of drums; but Minimal here, in Hood’s hands, becomes both reference to stripping down to the essentials – the stab of sickly discordant organ on ‘Unix’, the loping, filtering riff on ‘Station Rider’, the phasing pulse on ‘Sleep Cycles’ – and building them up into an intricate, interlocking mesh of sound; and, more obliquely, a hearkening to the classical Minimalistic compositions of the likes of Steve Reich, where arpeggios repeat and repeat and repeat and repeat, the tonality and timbre of the instruments changing through phase patterns like the opening of a filter or the discordant synthesis overtones moving against a bassline. Hood’s tracks have a restless fluidity, a swing and lope, and his riffs constantly move, spiralling up, or rotating together like parts in a machine. ‘Minimal Nation’ distills the most pure essence of techno into a perfect, machine-tooled mould that 18 years on has rarely, if ever, been bettered.”

52. Archers Of Loaf

Icky Mettle

(Alias Records, 1994)

We dare say that most indie fans worth their salt know ‘Web in Front’, Icky Mettle‘s opening track and one of the most distinctive guitar tracks of the 1990s, but what of the rest of the album? Taking the slack surrealism of Pavement, but upping the anger factor and earnestness (without, you know, becoming annoying), Icky Mettle finds the Carolina group tearing through classics like nobody’s business – from the drop-out anthem of ‘Wrong’, through the shrieking ‘You and Me’, to the gravel-rubbed ‘Learo, You’re a Hole’, it’s hit after hit; a storming opening statement from a group who, had things been different, could have been much, much bigger.

51. Pete Rock & Cl Smooth

Mecca & The Soul Brother

(Elektra, 1992)

Slow to shift units upon release, later years would see Mecca & The Soul Brother haunt hip-hop in both the US and UK – how many Pete Rock copycats, in both New York and London, did the turn of the 2000s see? None of them, naturally, touched the golden formula that Rock and Smooth achieved on Mecca, an album so smooth that at times it’s gaseous: reverberated bells hanging in the air, washes of ambience sweeping over tracks in a way that – believe it or not – wasn’t so common-place back in ’92.

50. Dr. Dre

The Chronic

(Interscope, 1992)

The Chronic. Unless something went horrifically wrong with your childhood, this entire record should have been burnt into your subconscious by your mid-teens, and every time you start to doubt it in the years since, it comes right back: let’s not forget, this is an album that features ‘Let Me Ride’, ‘Wit’ Dre Day’ and ‘Nothin’ but a G Thang’ in its first 5 tracks alone. If you don’t at least try to recite ‘The $20 Sack Pyramid’ in full every time you hear the words “swap meet”, then we’re no longer friends. Go spend a year at the doctor’s, and come back when you’re fully cured.

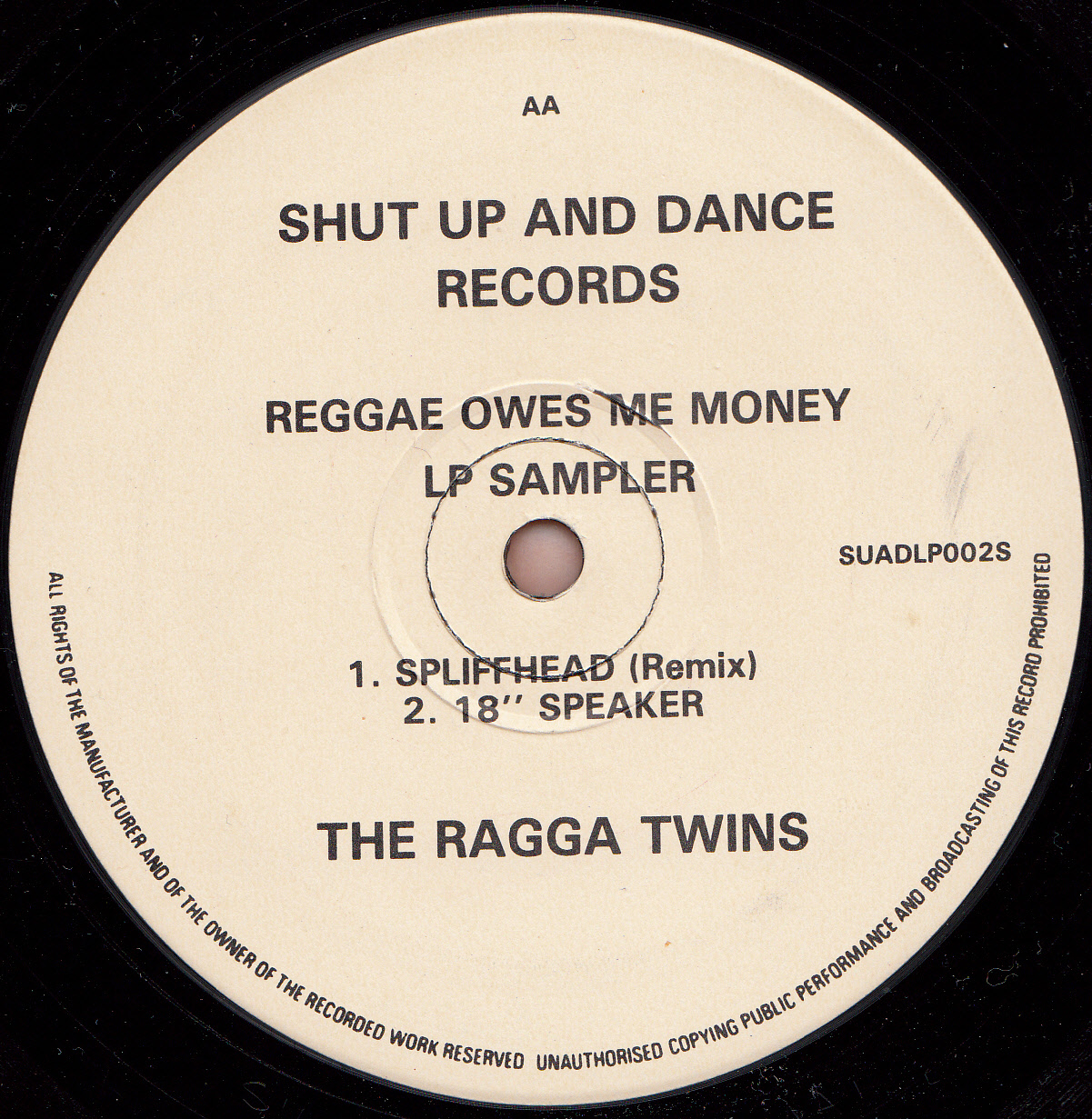

49. The Ragga Twins

Reggae Owes Me Money

(Shut Up And Dance Records, 1991)

The sort of magmatic fondue of acid house, breakbeat and dancehall that could only have existed at the dawn of the 90s. Not everyone mastered the blend (we see you, Silver Bullet), but, on Reggae Owes Me Money, The Ragga Twins skank all the way to the bank.

48. General Magic

Frantz!

(Mego, 1997)

Before Splazsh, we had Frantz!. Ramon Bauer and Andi Pieper’s genre safari takes in glitch, ambient, modern classical, trip-hop and drone – all seen through the same damaged cybertronic visor.

47. LFO

Frequencies

(Warp Records, 1991)

Frequencies isn’t just the best album to come out of the UK acid house explosion, it’s also reflects how alien and disembodying that music and the drug culture that sprung up with it must have felt to the first generation of ravers. It works as a dance record first and foremost, but also as a work of pure, exploratory, bass-heavy psychedelia.

46. Tricky

Maxinquaye

(Island, 1995)

In which our folk hero channels Beefheart, dismantles Public Enemy, grumbles like Bukowski and, despite making one of the most schizophrenic full-lengths of the decade, wins over the commonweal.

Mark Saunders (Maxinquaye co-producer/engineer): “It was the most bizarre record I’ve ever worked on. It was a complete un-learning experience and it was also a total re-learning experience. Think of how to make a record, then forget everything you’ve learned and start completely backwards and upside down. I could write a book about Tricky. He’s such a great character.”

45. The Martian

Lbh – 6251876

(Red Planet, 1999)

For our money the culmination of the Underground Resistance family’s techno experiments, ergo one of of the all-time great techno albums, period. It’s a compilation of tracks released on Red Planet 12″ between 1992-98 – pay particular attention to ‘Sex In Zero Gravity’, which is every bit as mindblowing as the act its title describes (we imagine).

44. Three 6 Mafia

Mystic Stylez

(Prophet Entertainment, 1995)

Ten years before ‘Stay Fly’, and fifteen or so before Three 6 tribute act Spaceghostpurrp, this Memphis group were making the world’s most ominous lo-fi – Burzum’s prison diaries, fall back. The production predates the “trap” style that’s currently so fashionable, and although Juicy J’s more catchy these days, he’s never sounded this effortlessly menacing.

Shlohmo: “Old cassette music, old Three 6 Mafia – it wouldn’t be good if didn’t sound as bad.”

43. Studio 1

Studio 1

(Studio 1, 1997)

Wolfgang Voigt was on fire in the 90s, working under a ridiculous number of aliases, and excelling in everything he deigned to attempt – from spiky acid house to classically-informed ambient. The pert, propulsive, dubwise techno he made under the name Studio 1 was so minimal it made Robert Hood sound baroque, and nearly 15 years later its cutting edge has yet to be blunted.

42. My Bloody Valentine

Loveless

(Creation, 1991)

The mythology of Loveless: Kevin Shields almost bankrupted Creation with the album’s endless recording sessions, and has been working on a follow-up ever since. The reality of Loveless: it’s held up better than any album by Primal Scream, Oasis, or any of Creation’s flagship bands, and it’s probably best that said follow-up never arrives. In the recent words of label boss Alan McGee, “I am 50, man, it’s over. Good luck, Kevin Shields: get on with it.”

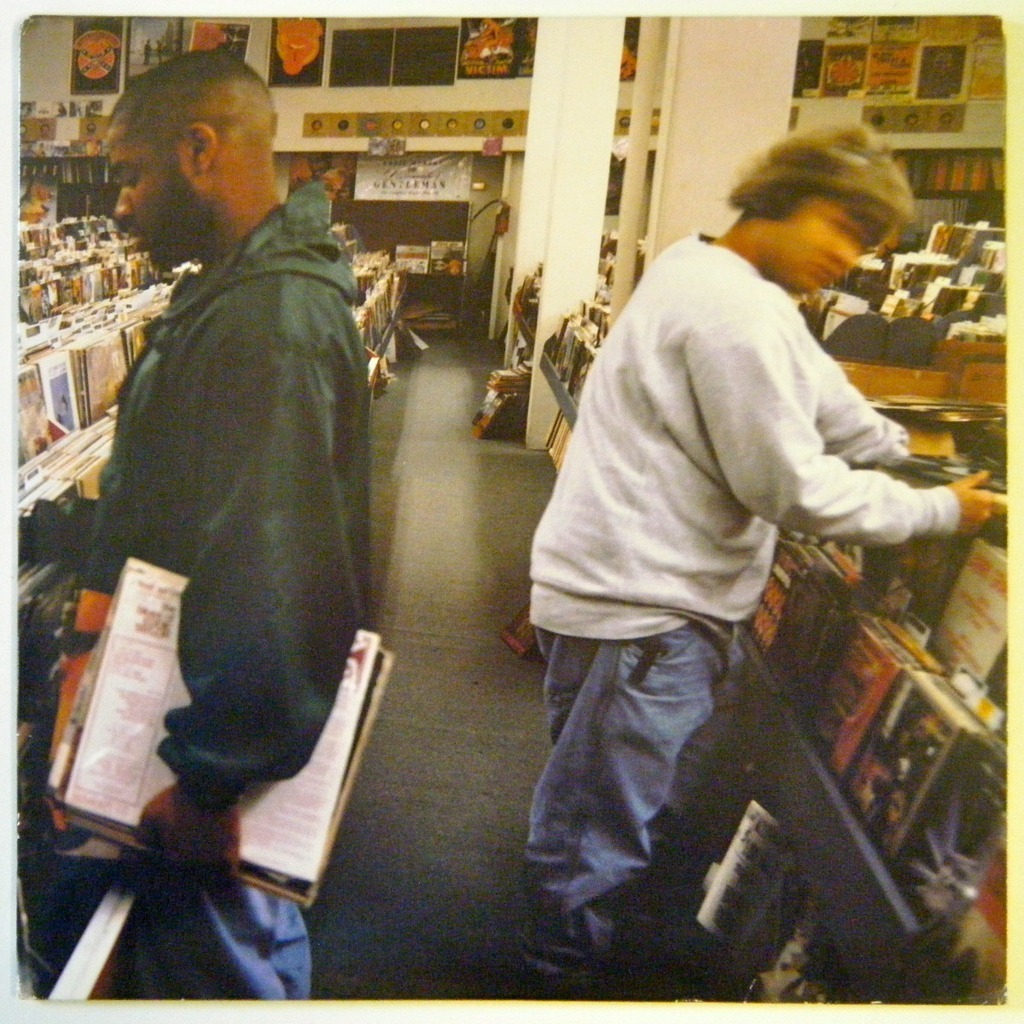

41: Dj Shadow

Endtroducing…

(Mo’Wax, 1996)

The decade’s great exercise in cut’n’paste. Swampy, noirish and endlessly surprising, there’s a reason why Endtroducing… has become alt.rap’s fattest holy cow – a chthonic antidote to The Chronic.

Ezra Koenig (Vampire Weekend): “This was such a good introduction to sampling, and the idea that modern music could be made from the past. It inspired me in a big way. I applied to Harvard, and I wrote an essay about Endtroducing… It was based around the idea that bringing things together in this way could be applied to all art forms.”

40. Arto Lindsay

Noon Chill

(Bar/None Records, 1998)

The most perfectly balanced of the avant-garde racket-maker’s exercises in uncanny Tropicalismo. Delicate as rice paper, intricate as origami.

39. Sensational

Loaded With Power

(Wordsound, 1997)

Stumbling from the wilderness, mouth parched and hands scratched, the Jungle Brothers affiliate offers up one of hip-hop’s strangest pieces of folk art. Lo-fi in excelsis.

38. F.U.S.E.

Dimension Intrusion

(Warp Records, 1993)

Dimension Intrusion was the debut album release by Richie Hawtin, and captures him at his superhuman best, before his pursuit of extreme minimalism squeezed pretty much all vestiges of soul and funk out of his music. Released as part of Warp’s IDM-defining Artificial Intelligence series, its vision of ambient techno continues to sparkle and seduce today.

Dominick Fernow (Prurient, Vatican Shadow): “The first time I heard F.U.S.E. was 19 years ago in rural Wisconsin. The last time I listened to F.U.S.E.’s Dimension Intrusion I was driving from the port of L.A. through downtown at night amidst the illuminated skyscrapers. A perfect chess piece balancing the morning drive through south central set to Godflesh’s Streetcleaner. I was in an aerodynamic futuristic white rental car convertible with degrading subwoofers, subconsciously applying the gas. Before I knew it I was slamming on the brakes. The true ‘nitedrive’.”

37. MF DOOM

Operation: Doomsday

(Fondle’Em Records, 1999)

MF DOOM’s decade reads like a morality play: a steady rise to fame with KMD; label chicanery and personal tragedy; years pottering in obscurity; a cussed reinvention; and, to close, Operation: Doomsday, a triumph of automatic writing and the first act in his masterful second career.

36. John Oswald

Plexure

(Avant, 1993)

Oswald’s mission – to chop and cram the entire history of pop music into a 20 minute suite – is a daunting one, and the results are akin to staring directly into a bit-torrent. Oswald darts from Girl Talk tomfoolery to proto-gabba to genuinely terrifying sonic overload. In a world where more and more fingers are grafted to the skip button, Plexure plays like the most prescient record of the decade.

Dan Lopatin (Oneohtix Point Never): “For me, John Oswald’s plunderphonics project wasn’t just about vandalism or détournement: it was about the aesthetics of a cut, and how Oswald was able to so craftily reframe the fabricated hubris of pop music into something sardonic and telling.”

35. Goldie

Timeless

(Metalheadz/Ffrr, 1995)

Enabled by the not inconsiderable engineering talents of Rob Playford and 4Hero, Timeless didn’t just define drum’n’bass in the eyes of the mainstream, and while its unapologetic grandiosity wears a little thin across its overlong duration, at its best (‘Timeless’, ‘Sea Of Tears’) it soars higher than any music we’ve encountered before or since. Timeless still stands today as a future-facing, visionary work, and it feels as much a part of the prog/fusion tradition of ’70s Miles, Coltrane and Mahavishnu Orchestra as of the UK hardcore continuum.

Loefah: “You know, Timeless didn’t need jungle; if anything jungle needed Timeless. That album stood alone. It didn’t need its scene, it didn’t need anything; it was incredible. The mastering, the packaging, the production…that’s what we need to be doing. We need to be rolling with those levels of quality.”

34. Eric’s Trip

Love Tara

(Sub Pop, 1994)

Not just one of the ’90s’ best indie albums, but its greatest break-up album too. Rick White and Julie Dorion wrote Love Tara while in the process of breaking up – so Rick could be with another musician named Tara S’Appart, no less – and it tells: a spellbinding world of tape hiss, answer-phone messages, awkward silences and exclamations of rage that should be as widely known as the Sebadoh and Pavement albums of the same era.

33. Portishead

Dummy

(Go! Discs, 1994)

It’s been plundered by the ad agencies, scalped for chill-out comps and bent over and branded with the ‘dinner party album’ stamp – so how does Portishead’s unit-shoveller still sound sound so brittle, so eerie, so downright other?

Gonjasufi: “Beth Gibbons. Just from where she’s singing from, man. The pain that’s in it. I feel like I’m in a room when I hear her voice, I can smell, I can see the whole setting, the ambience…A lot people are trying to be different, and they start trying to sound like her. There’s a whole genre of everyone trying to sound like Björk and Portishead. But what makes them so special is that they don’t sound like anyone. It’s okay to not sound like anyone, but don’t sound like them and then try to pretend you don’t sound like them, you know what I’m saying?

32. Scarface

The Diary

(Rap-A-Lot Records, 1994)

Has an album ever delivered lyrics as bloodcurdling as “look deep into the eyes of your motherfucking killer / I want you to witness your motherfucking murder, nigga”, or, indeed, the timeless “I can’t talk to my mother, so I talk to my diary”, with such casual, nonchalant bounce? Three 6 Mafia, Esham et al aimed for menacing, and that’s the difference: The Diary‘s so far gone, so heartless that its tales of murdering families and crippling paranoia attacks are delivered with the same cadence as sex jams like ‘Goin’ Down’.

31: Robert Rich & B. Lustmord

Stalker

(Fathom, 1995)

In 2012 you can’t throw a pebble without hitting a “dark ambient” album of some kind, but in 1995 Stalker felt like an act of brooding dissent amidst the fluffy chill-out that had come to dominate the post-rave musical landscape. Lustmord, an artist whose technical prowess had by this point taken him from the UK industrial underground to the more salubrious world of Hollywood sound design, collaborated with veteran space-case Robert Rich on this sumptuous set, loosely inspired by Tarkovsky’s film of the same name. Forbidding though it may seem, its magic in fact lies in its tempering of darkness – it is, in the end, a piece of work poised improbably between the New Age and the gothic.

Lustmord: “It’s one of the few albums that I’ve worked on that I still liked after finishing it…it is remarkably effective, and I suppose that’s because we had a very good idea of what we wanted to achieve before starting on it.”

30. Boards Of Canada

Music Has The Right To Children

(Warp Records, 1998)

Music Has The Right To Children isn’t just a great record: it’s arguably the most influential (and we’d wager, best-loved) album Warp have ever released. The Sandison brothers’ debut proper isn’t quite their masterpiece – we’d argue that 2002’s Geogaddi takes that crown – but it’s still an astonishingly sensitive, remarkable focused collection of eerie miniatures and Betamax fantasias. A holy text for 2012’s motley crew of cloud-rappers, chill wavers and synth revivalists, Music Has The Right To Children is electronica’s own Miss Havisham – dolorously strolling through memory’s mirrored corridors, and chancing across all manner of cobwebbed treasures on the way.

29. Ken Ishii

Garden On The Palm

(R&S, 1993)

Full to bursting with ideas, Ishii’s mercurial debut – a set running the gamut from piebald techno to submerged acid house – is one of R&S’s most lucent buried treasures.

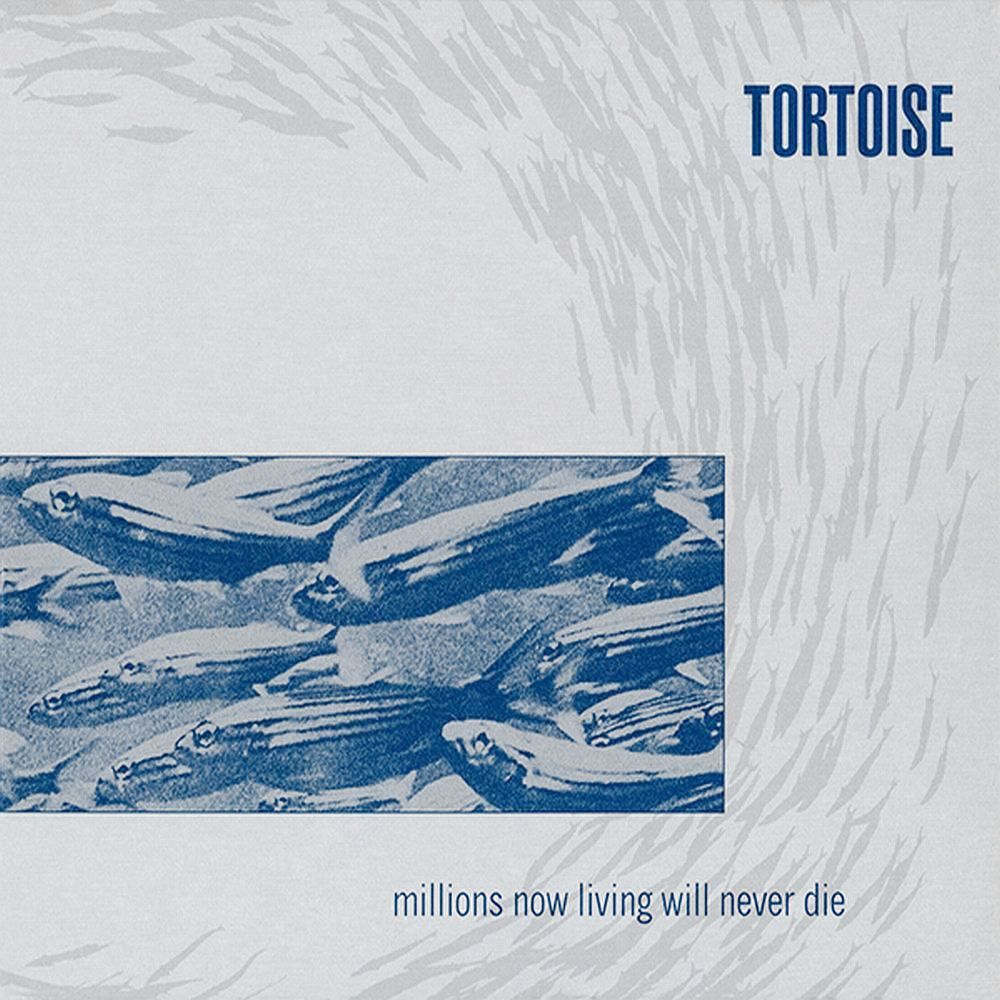

28. Tortoise

Millions Now Living Will Never Die

(Thrill Jockey, 1996)

Purists swear by the Chicago group’s self-titled debut, but wild horses couldn’t drag us from the certainty that Millions Now Living Will Never Die is Tortoise’s greatest achievement. It’s wasn’t so much post-rock as post-everything: we can’t think of any band since that has made such a definitive break with the past.

Doug McCombs (Tortoise): “It was pretty ambitious and we did a good job of it but it was never really completely finished, we didn’t have the resources. There was a sense of ‘this is what we have and this is going to have to do.’ There are some successful experiments on it, and some loose ends.”

27. Neurosis

Through Silver In Blood

(Relapse, 1996)

The fifth album by this Oakland, CA sextet was at the time merely a mind blowing slab of post-hardcore/sludge/industrial metal, its 12-minute songs and sensory overload alienating more listeners than it seduced. In hindsight, it seemed to set the scene for all post-metal ever, but none of those records would ever capture the combination of ambience, crushing heaviness, layers of samples and outright malice of this living, breathing, relentless 70-minute beast. Strip away the guest instruments and the loops, and you’re left with some of the finest riffs as tectonic shifts known to humanity.

Steve Von Till (Neurosis): “The making of it is not negative. The making of it and the channelling of it is the positive part. It’s the shit behind it that’s negative. There’s negative shit in life. There’s negative shit in the universe. There’s negative shit preying on people’s minds and hearts all the time. And this probably more than any other record was a direct confrontation with that, as younger men, without the knowledge that we would survive it…It was punishing. It was furious. It was completely aggressive and destructive. If you want to subject yourself to this music, you are going to be subjected to this music. It used to make people sick, and that’s an appropriate response!

“I can’t get back into the mindset we were in back then, nor would I want to.”

26. Polygon Window

Surfing On Sine Waves

(Warp Records, 1993)

Richard D. James’ only full-length as Polygon Window is, to all intents and purposes, an album of openings. His first release on Warp, and the first full-length proper in that label’s peerless Artificial Intelligence series, it clears the ground for James’ astonishing 1993-7 run of releases – arguably the finest run of form by anyone, anywhere, all decade. Musically, it’s airy and expansive; creatively, it takes acid/ambient into unchartered new territories. More than anything, though, Surfing On Sine Waves is open-hearted. From top to tail, it’s a haunted, hurting, melancholy record: an album of vistas glimpsed through dust-flecked double-glazing. Ravey one moment, stately the next – but somehow still one of James’ most coherent statements.

25. Genius/GZA

Liquid Swords

(Geffen, 1995)

Wu represented a slight point of contention while compiling this list: how many albums can you viably include from hip-hop’s greatest group? On any given day, Return to the 36 Chambers, Only Built for Cuban Linx, Tical and maybe even Bobby Digital in Stereo could have made this top 100, but for once, we decided to be sensible and restrict the Clan’s individual members’ output to just the one record. Once we’d made that choice, it wasn’t a difficult call: with each year that passes since its release in 1995, Liquid Swords’ status as the greatest Wu solo album seems less and less in doubt – as brutal, cold and quotable as it ever was.

24. Jim O’Rourke

Eureka

(Drag City, 1999)

The brutal truth is that most avant-garde musicians choose experimentation over pop because they lack the confidence, ability and perhaps even the human touch to pull off the latter. Not so Jim O’Rourke, who, having spent most of his career working with the likes of Phil Niblock, Keiji Haino, Tony Conrad and Evan Parker, tried his hand at left-of-centre song craft on 1999’s Eureka and proved to be more than up to the challenge. Whether transforming Ivor Cutler’s ‘Women Of The World’ into a cyclical folk-rock symphony, delivering a splendidly faithful cover of Burt Bacharach’s ‘Something Big’ or offloading timeless originals of his own, O’Rourke’s every move on Eureka made our teenage selves swoon, and our appreciation of his achievement has only deepened in the intervening years.

Jim O’Rourke: “The record has the appearance of being cheerful…but it’s fairly misanthropic underneath the surface.”

23. Drexciya

Neptune’s Lair

(Tresor, 1999)

James Stinson and Gerald Donald’s word as Drexciya could never be summed up by one record: it’s too vast for that, too drenched in mystery and back-story, too damn deep (aquatic punning unintentional – honest), but Neptune’s Lair is probably the best introduction a wave-jumping novice could have to techno’s all-time most mythologised group. Plus, obviously, it features ‘Andreaen Sand Dunes’.

Serge (Clone Records): “Fortunately Drexciya still needs to be introduced to general music listeners, mainly due to their self chosen anonymity and their productions being made in the pre-internet and early internet era. I say fortunately because I think their music is special and should be discovered by the listener, rather than being pushed or promoted as a product. These guys have played such an important role in the development of techno and electronic music in general that I hope everyone will discover them at some point in their life.

“With no documented information about the producers, their thoughts and ideas, the lack of interviews, the mystery became bigger with each release. Who are these guys, why did they make music they made, how did they make it and actualy who did make it? Questions that are still not completely answered. From their first releases on Submerge and Underground Resistance to the later ones on Tresor and Clone they always managed to come with releases covered in mystery. And instead of having technology or “the future” as influence like so many techno producers they had their own unique approachs and imagination which – I assume – sprouted from their frustrations, experiences, interests and life in general being young (non-stereotype) afro-Americans in Detroit.

“Their later releases such as the great Neptune’s Lair and Grava4 stand on their own as concept and perfectly showcase the beauty and warmth, but also the rawness and non-conformist spirit of Drexciya.”

Jackmaster (Numbers): “Anyone who follows Numbers or follows me is probably sick to the back teeth of hearing about Drexciya, but it’s one of the things that really draws us together. If you were ask any of the people behind Numbers, we’d all put them in our top one or two influences, or favourite groups.”

22. Snoop Doggy Dogg

Doggystyle

(Death Row Records/Interscope, 1993)

People talk about Doggystyle like it’s a laugh, and it is – as anybody who saw Snoop’s absurd start-to-finish live performance of it in London last year, complete with ‘The Bathroom’ acted out on the big screen, will testify – but it’s also sort of a tragedy. For 19 tracks, Snoop rips through verses like he doesn’t know any other way: in terms of a rapper sounding like an unstoppable force, it’s easily up there with Notorious B.I.G.’s Ready to Die, or prime Ghostface, leaving you with the impression that the only way to stop Snoop rapping would be to shoot him there and then. Passion, skill, power, it’s all there; what a shame he got bored so quickly.

Flying Lotus: “My whole life was Doggystyle. I wasn’t allowed to listen to it but I knew an older kid who had it on CD, so I made a tape of it. I had the ugliest yellow waterproof tape player ever. It was like this industrial brick. But that’s what I listened to Doggystyle on.”

21. Oval

94Diskont.

(Mille Plateaux, 1995)

Yes, ‘IDM’ was the daftest tag of the decade, but surely ‘glitch’ gets an easy ride? 94diskont.’s a case in point – if there’s a bug in this serene, somatic, and impossibly graceful record, we’ve yet to spot it.

Markus Popp (Oval): “Even though the entire game has substantially changed since 1992, I still consider myself first observer, then artist/musician.”

20. Rowland S. Howard

Teenage Snuff Film

(Reliant Records, 1999)

Was there a greater, more affecting rock ‘n roll album than Teenage Snuff Film released in the 1990s? It’s the barbed, bleak but ultimately redemptive sound of a booze and drug-ravaged romantic, one who happens to be the most gifted guitarist of his generation, coming to terms with the mistakes he’s made, the love he’s lost and the man he’s become. “I choke on this heart of hate,” he declares on ‘Breakdown (and Then…)’, before admitting, “Sometimes I find it hard…to get things straight.” Rowland S. Howard died of cirrhosis of the liver in 2009. He is nothing less than a martyr, and Teenage Snuff Film is his lasting monument.

Regis: “Rowland S. Howard quite simply is beyond comparision. His guitar-laying could penetrate the soul in a way that no one else’s could. His stage presence was remarkable and for me unforgettable in every way and detail – no man has ever looked as good, or ever will look as good, playing a Fender Jag. Teenage Snuff Film is where, thanks to Mick Harvey, he was able to refine his sound and transform the film noir torment that he displayed with The Birthday Party and These Immortal Souls into glorious, widescreen technicolor.”

19. 69

The Sound Of Music

(R&S, 1995)

Carl Craig might not have been one of Detroit techno’s earliest originators, but he has done arguably more than any of the Belleville Three to develop the sound, and enjoyed a rangier, more prolific and frankly more consistent career. His releases between 1991-94 as 69 were what fixed him in the world’s eyes as an artist of major stature – from the soaring, post-Skynet soul of ‘Desire’ to the priapic dancefloor funk of ‘Jame The Box’, via the pure sub-bass tone poetry of ‘Sound On Sound’, it’s a visionary, effervescent body of work, and The Sound Of Music, a compilation released by R&S in ’95, groups the best of it together in one place.

18. Shellac

At Action Park

(Touch And Go, 1994)

Steve Albini may be best known as one of rock music’s most in-demand engineers – not to mention one of the genre’s most infamous bastards – but in between recording albums by Nirvana, Pixies, PJ Harvey and more in the early ’90s, he also slipped out one of its most brilliantly angular rock records. Combining Minutemen-esque grooves that feel like they could last forever with spit-riddled, sneering vocals and a storming rhythm section, there are few albums that sound as simultaneously doomed and driven as At Action Park.

![]()

17. Icons

Emotions With Intellect

(Modern Urban Jazz, 1996)

Timeless, Modus Operandi and New Forms might have made more of an impact, but it’s the relatively undersung Icons who made the finest drum ‘n bass album of the decade. On Emotions With Intellect, Tony Bowes and Conrad Shafie – much-loved for their work as Blame & Justice – combined breathtaking atmospherics worthy of the loftiest Detroit techno with rugged, streetwise drum programming, and somehow managed to avoid self-indulgence while they were at it. A stone cold classic – let the revival start now.

16. Massive Attack

Mezzanine

(Virgin, 1998)

A world without light, soundtracked by washes of oxidised piano, growling basslines and guitar licks distorted beyond recognition, Mezzanine is, and always will be, the best Massive Attack album. From the jet-black drowning pool of ‘Angel’ onwards (yes, we’ve all heard it far too many times, but to deny its status as a masterpiece is just silly at this point), its journey through the red-eyed introspection of ‘Risinson’, the murmuring undergrowth of ‘Inertia Creeps’, the echo chamber hip-hop of ‘Black Milk’ and the stirring ‘Mezzanine’ simply doesn’t let up – a miracle indeed, when you consider some of the dodgy lyrics it contains.

Robert Del Naja (Massive Attack): “I was the only one at the particular time that had a vision of how this album could sound as a whole. Everyone else had fragmented ideas and that’s good sometimes and dangerous other times. We’d been fucking around for a long time and it was about time to finish the album, d’ya know what I mean? It wasn’t fucking easy. It was painful—the arguments and everything else. But it had to be done, otherwise we’d still be fucking around now discussing what kind of album we’re gonna do.”

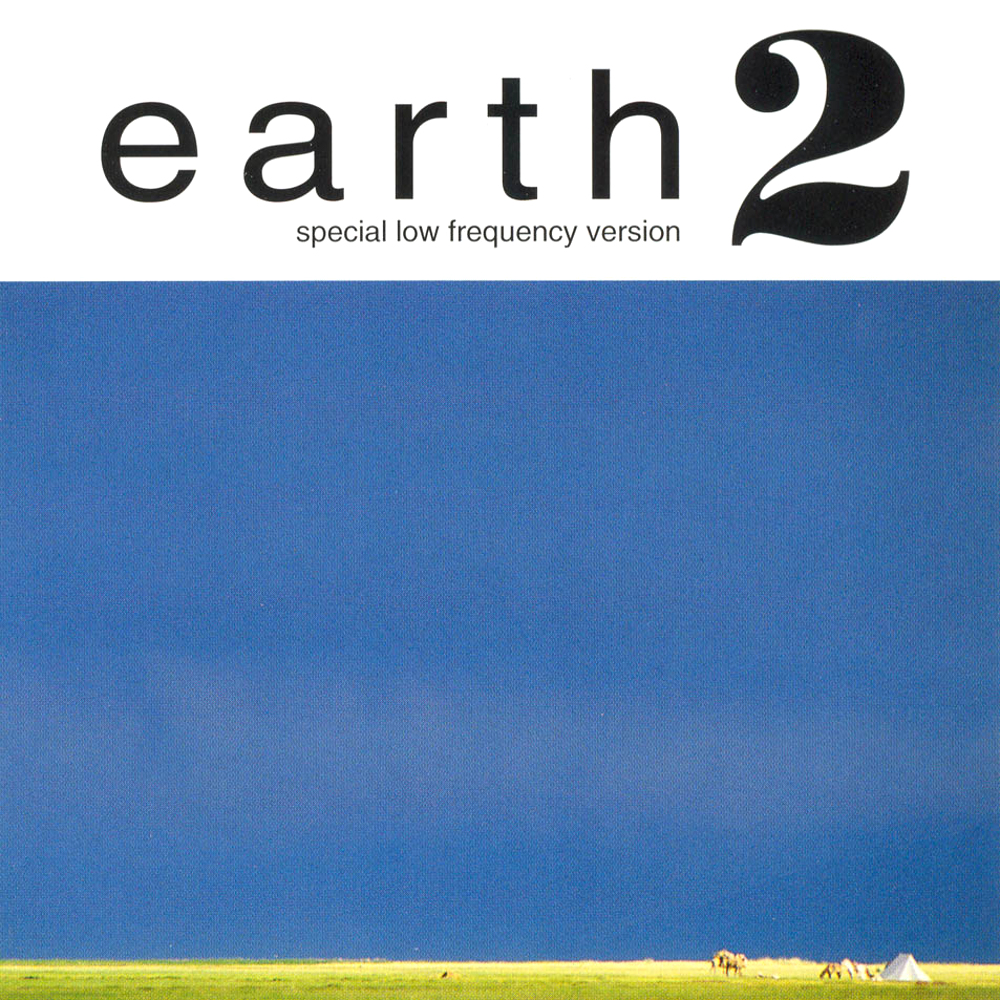

15. Earth

Earth 2: Special Low Frequency Version

(Sub Pop, 1993)

Don’t believe what Patrick Moore tells you: Sunn couldn’t exist without Earth. So inspiring to Stephen O’Malley’s doom powerhouse that he named two bands after them (SunnO))), after their amplifier of choice, and Teeth of Lions Rule the Divine), Earth 2 finds the group stripped down to a two-man team – Joe Preston and the ever-present Dylan Carlson – and remains their genre-defining masterpiece, an album that moves like a island being slowly submerged in magma.

Raime: “Literally the sound of metal – in both senses – being melted down. It’s like someone physically manifesting their intentions in frequencies. Some metal guys weren’t into it, too simple or cosmic perhaps. But to us thats the point, it’s way out there but feels somehow innate and essential. Metal had always had sense of dynamism that made aggression cathartic through action, but this was the opposite, this just said fuck it, be swallowed by the void, let go…”

14. GAS

Konigsforst

(Kompakt, 1999)

Superlative amniotic techno from Wolfgang Voigt’s grandest, most enduring and most prophetic project. The illegitimate father to Clams Casino and Claro Intelecto alike.

Fred Macpherson (Spector): “As someone who grew up listening to overly compressed ’90s pop and variously inane and obnoxious indie rock bands, the first time I heard Wolfgang Voigt’s GAS was nothing short of an epiphany. Like the forests that adorn most of the GAS covers, the music is natural, immersive and endless – almost as if it wasn’t recorded to be listened to, but to be breathed.”

Wolfgang Voigt (GAS): “When I was working on Konigsforst, I was envisioning a sound body ranging somewhere between Schönberg and Kraftwerk, between bugle and bassdrum. For me Konigsforst is Glamrock as Wagner, Hansel and Gretel on Acid. An endless march through the undergrowth – into the disco – of an imaginary, misty forest. When I look back on it today, the most joyful and surprising thing about it, is that so many people world-wide obviously understood the record exactly the way I intended it to be heard. I never expected that when I made it.”

13. Diamond & The Psychotic Neurotics

Stunts, Blunts & Hip-Hop

(Chemistry/Mercury)

Woebot: Stunts, Blunts & Hip-Hop was one of the most satisfying manifestations of what will remain to many the true Golden Age of Hip-Hop. Although it was produced by Diamond D, legends Large Professor, Q-Tip, Jazzy J, Showbiz and DJ Mark the 45 King also lent a hand. At that point in time, before lawyers limbered up and the seam became exhausted, digging in the crates (an activity enshrined in the crew’s moniker D.I.T.C.) must have seemed like it would be an eternally rewarding experience. Edging past the first wave of samples dug by Marley Marl and Eric B, often well-known James Brown fare, suddenly it seemed there was an ocean of juicy funk and jazz breaks that had never been used before. The delight and excitement is palpable. As if that wasn’t enough, Diamond’s lyrics are witty and often moving, the title track in particular, a paean to what hip-hop meant as a way of life, has been known to draw tears and gives the LP the edge on the other masterpieces of the period – Low End Theory, Runaway Slave, Mecca and The Soul Brother, Breaking Atoms and Enta Da Stage.

12. Talk Talk

Laughing Stock

(Verve/Polydor, 1991)

For a record of such mighty ambition, Laughing Stock still feels oddly humble. Maybe it’s context: arriving in the same year as some proper Mega-Albums (Nevermind; Loveless; Achtung Baby), it’s frequently – and inexplicably – cropped out of history by many less-than-rigorous retrospectives. Or maybe it’s just that Talk Talk’s final transmission is too immaculate, too delicate, to waste its time on hollow bombast and self-promotion. Sprung from the same batch of magic bean as Spirit Of Eden, it outclasses its predecessor in just about every category: everything about Laughing Stock – New Grass” coruscating reverb-play, ‘Ascension Day”s hidden temper, the all-enveloping organs on ‘After The Flood’ – speaks restraint, élan and immaculate taste. The marginal masterpiece of the decade.

11. Autechre

Incunabula

(Warp Records, 1993)

Is there a better named record on the list? An incunable, if you’re wondering, is a broadside produced in the immediate wake of the development of the printing press. Fittingly, Manchester duo Autechre’s 1993 debut delights in – fetishes, even – the shock of technology.Incunabula is a symphony of whirrs, cranks and rattling spokes; its formal ingenuity and sheer, brute intensity have sealed its status as a set text for the ages.

Zola Jesus: “I first listened to Autechre in high school, I don’t even know how I discovered it but I liked how for some reason it made sense to me, even as someone who mostly listened to punk and noise. Autechre have always had this unique sense of intuition and innovation in what they do. It feels very raw and revolutionary. The repetitions and movements move like a body would.

“Incunabula really represents this. It feels like a body, every song has a heartbeat with the beat or hi-hats, and then everything around it moves and pushes and weaves and creates micropulses. Some sounds are stark and clinical and others are languid and thick like blood pushing through veins. It is singlehandedly the most organic and undeniably synthetic electronic music I have ever heard, and that’s what I think has made that duo one of the most seminal electronic acts of our time.”

10. Angelo Badalamenti

Music From Twin Peaks

(Warner Bros, 1990)

Harleys, leather, doo-wop harmonies, doe-eyed jive talk…Twin Peaks was set in the ’90s, but if sure felt like the ’50s. Same goes for Angelo Bandalamenti’s landmark soundtrack: this is détourned library music, kitsch gone wrong, all American cherry pie left to curdle. Few records have quite as much Pavlovian pull; in the next ten years, no other OST would come close.

Angelo Badalamenti: “The fact that people are still talking about it is a tribute to my great friend David Lynch. The music was such an important part of that show, almost as if it was a major character.”

9. Swans

Love Of Life

(Young God, 1992)

It may be a far cry from the chain-pounding aggression of records like Filth, but 1992’s Love of Life hardly finds Swans optimistic. If there’s a stance to be found here, it’s band leader Michael Gira as observer, touching on ideas of commitment, hope and, yes, love, but never quite committing to them. ‘The Other Side of the World’, voiced by Jarboe, narrates a continent-shifting moment of closeness; likewise, ‘Her’ finds Gira dedicating himself to a mate, but the overall feeling of both tracks – and much of Love of Life – is that these moments are powerful but temporary, an impression echoed by the recording of the lovestruck girl at the end of ‘Her’. The CD version of the album closes on ‘No Cure for the Lonely’, a final reminder of the mortality of both humans and relationships, and one of the very best individual songs in Swans’ vast back catalogue.

8. Main

Motion Pool

(Beggars Banquet, 1994)

Robert Hampson remains best known for his first band, Loop, a space-rock unit whose work, for all its virtues, always sounded pedestrian when compared to the work of their contemporaries, Spacemen 3 and My Bloody Valentine. In his post-Loop work with Scott Dowson as Main, however, Hampson would create the era’s most singular guitar music – deconstructing the instrument, gradually divorcing it entirely from its rock associations. Motion Pool, the first Main full-length, was a leap into radical, dub-wise repetition and abstraction that made Pete Kember, Jason Pierce and Kevin Shields look like pussies, quite frankly; its brooding, sensuous textures and tonalities all the more remarkable amid the vestigial presence of vocals and conventional song-structure. Is this a rock album? Yes, perhaps, but one that sounds more alien and futuristic than any “electronic” music released the same year.

Robert Hampson (Main): “Motion Pool was a very definite and deliberate statement. I said to our then manager and record company, ‘This is what it’s going to be. It’s literally the tail-end of what people know, and then it’s a whole new ballgame after that.”

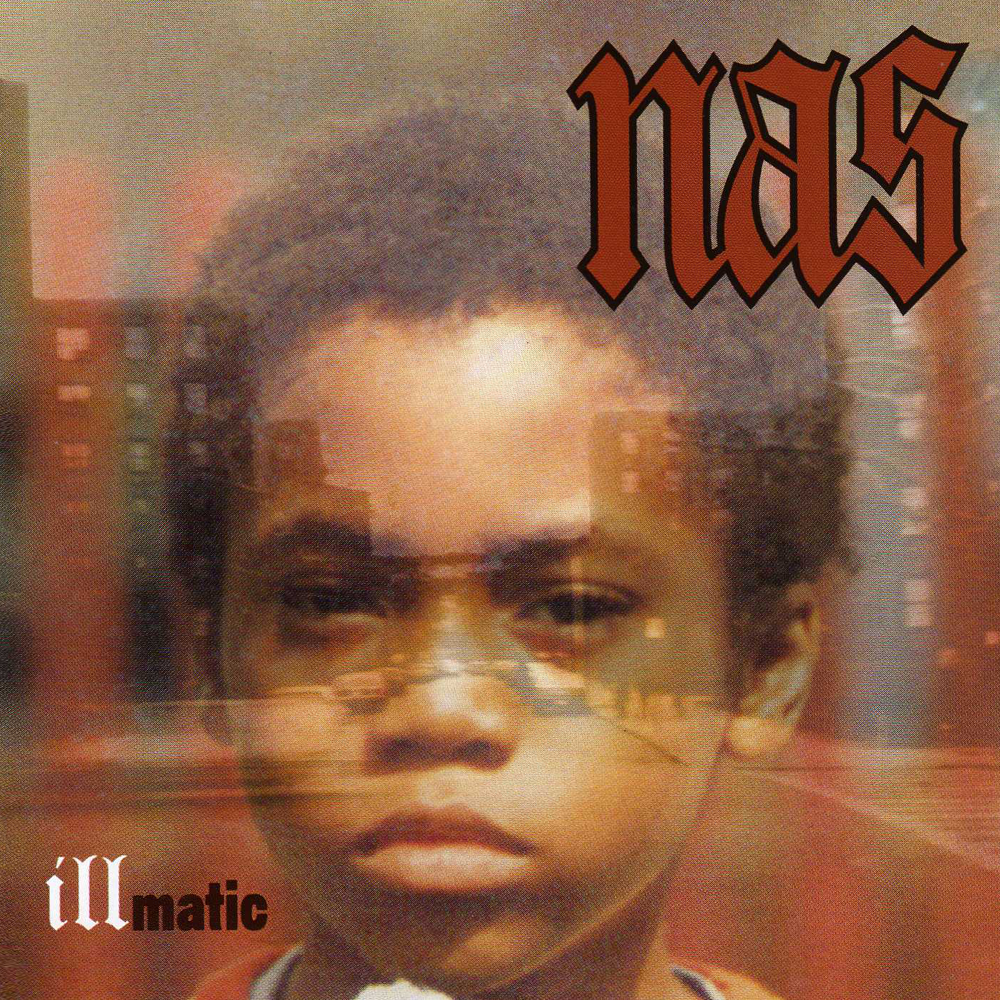

7. Nas

Illmatic

(Columbia, 1994)

Illmatic was one of few breakthrough hip-hop albums that is utterly solid from start to finish, the kind of hip-hop opus you can’t bring yourself to skip through. No wonder Nas’s career has been haunted by the spectre of almost-brilliance ever since – this is the kind of debut that is simply impossible to better, packed with memorable lines, evocative lyricism, and a roll-call of outstanding producers at the top of their mid-nineties game, from Premo to L.E.S. to Large Pro . An early version of this record surfaced recently on the net called “Nasty Nas – 1991 Demo”, and it seems from listening to the prototype that many of the standout moments here were in development for quite a while, from the filtered loop of Michael Jackson on ‘Ain’t Hard To Tell’, to the gritty visions of Queensbridge life that adorn ‘NY State Of Mind’. The truth is, few on planet earth can rhyme like this, and few ever will again.

El-P: “New York kinda has it tough. We are always the subject of film, music, art, etc. but rarely does the New York we know really get portrayed. It’s always some corny shit. Some half assed exaggeration or myth that doesn’t really match up to the truth or the feeling of NYC. Anyone who grew up in New York City can tell you there are things about New York City that cant really be explained directly. You have to talk around them. Show them. Paint the scenery around the details and hope that the intangible, gritty, beautiful things that we see and feel here can be invoked, not described. As New Yorkers we get very excited when anyone portrays New York and New Yorkers from the inside out. When the characters talk the way New Yorkers really talk. When the settings portrayed feel like New york Feels. Smell like they smell. There have been a handful of pieces of art that have, in my life, made me feel like my city makes me feel. Henry Chalfant’s 1983 documentary Style Wars is one of them. Wild Style is another. Illmatic by Nas is another. Fitting that nas chose to set off this amazing record with a sample of dialog and music from Wild Style. It immediately connected him to a spirit and intention born of legend, art and the truth of New York.

“Before Illmatic dropped everyone knew who Nas was, but no one knew what the kid who said “when I was twelve, I went to hell for snuffing jesus” was going to sound like when given his own album. The mystery surrounding the project was palpable and real. What was this going to to be? Some story shit? Some dope but exaggerated shit? Punch lines? Gangster shit? Thoughtful shit? No one knew. Remember?

“I remember my friend Tom came through with the tape (yes, tape) and $25 worth of weed. I don’t know how he got it. It wasn’t out yet and The Internet basically didn’t exist. We listened to that shit for about four straight hours. Silently. Flip the tape again. And again. Again. Holy shit either I’m way too high or this motherfucker might the best rapper alive.

“A truth speaker. A historian. A bad and good kid. A smart, tough, slick kid, soaked in hip hop. Talented as all Hell and thinking his way out of a hard place. Flawed and fly and sharp witted and here to be nothing more than what the truth of the city is.