“I got a lot of flak when I opened Factory’s offices as a club. I got a lot of flak when I started doing the Joy Division music again, and I expect I’ll get a lot of flak for doing the fucking book.”

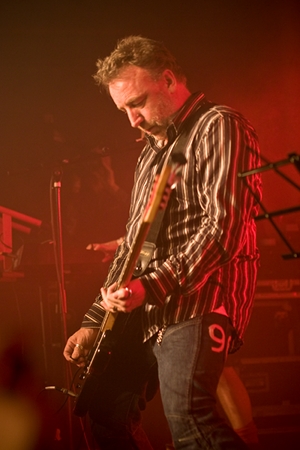

The “fucking book” to which Peter Hook is referring is Unknown Pleasures: Inside Joy Division, his first-hand account of the band’s birth, life and tragically premature end. It hits stores this Thursday, 27 September, and will be supported by a book tour commencing in Manchester on October 1 – for full dates, click here.

FACT’s Kiran Sande called up Hooky last week to discuss this and life outside New Order, and found him in surprisingly wry, self-effacing, at times even pensive form. “It’s like me clearing out my metaphysical loft,” the bassist says of his memoir. “I’ve cleared it all up, made a list of it all, and it’s lot tidier than when I first went in…”

“Hindsight’s a wonderful thing, isn’t it? A wonderful thing that you only get afterwards when you can’t do a fucking thing about it.”

What prompted you to address the subject of Joy Division now, head-on, after all this time?

What prompted you to address the subject of Joy Division now, head-on, after all this time?

“You have to bear in mind it was finished a long time ago – it’s all moved quite slowly [laughs]. The thing is, when New Order split up in 2006, I found myself on the outside for the first time, shall we say? When I was in New Order it always felt perfectly natural and perfectly normal to ignore everything, really, to do with Joy Division. We very rarely had anything to do with it, we never celebrated anything, we never played a lot of the music, we hardly did anything. Once I was outside of that, it struck me as odd, and I thought, why do we never celebrate anything? It just seemed really weird.

“The idea for celebrating Ian’s 30th anniversary was because we’d never done anything before, and it just seemed fucking ludicrous to me, to be honest. I got the idea for playing for the album off [Primal Scream’s] Bobby Gillespie, because he was playing Screamadelica in full, and it just struck me that there are certain songs on your LPs that you loved on the record, but that you never played live. And I thought it would be a challenge to play ’em, you know? It was as simple as that.”

“Everyone was amazed at Ian’s pool playing technique.”

But what about the book?

“The book came about because – well, obviously I knew that I could do it, ‘cos I’d done the Hacienda book. And I was sick of reading books about Joy Division by people that weren’t there. It was Mick Middles’ book that finished me off, actually. Mick Middles and Lindsay Wilson’s [Reade’s] book, I thought fuck, this is ridiculous, I’ll do a fucking book, d’you know what I mean? So it came out of that.

“I started it about two and half years ago and I only finished it six months ago. So it took me two years, literally I sat down with partner, Andrew, and we did about 46 hours’ worth of interviews, over a few days. Me going over and over everything I could think of. Andrew collated it all for me, and then I started writing the book. I did this one quicker than the Hacienda book – the Hacienda book I must’ve re-written at least a hundred times. And with this book, I probably only re-wrote it about 80 times. So I’m getting better – by the time I get to the New Order book, I should be whizzing through it [laughs].

“I was sick of reading books about Joy Division by people that weren’t there.”

Did the memories come easily, and perfectly formed? Or was there a lot of head-scratching, a lot of piecing together of loose strands and fragments?

“Well, there were a lot of things that were jumbled up, and to be honest with you there a lot of things that have clarified recently. It’s only now that I’m like, ‘Ah fuck, now I remember!’. Too late, you know what I mean? So there are a few things like that I’ve only now got to the bottom of, shall we say. There are also a few things I’ve since remembered that I now wish I’d put in the book.

“For example, I remembered how Ian used to played pool: he always used to play pool with one fag in his mouth, one hand with the fag, and he always used to hold the queue with one hand, right, and he’d just blam it off the table with one hand. He used to play pool like he used to dance on stage. He’d be running around the fucking pool table – I only remembered this recently, and thought it would’ve been fucking great in the book – and, amazingly, he was really good at it. He’d whack it like a madman and the fucking thing would go in. Everyone was amazed at his pool playing technique. So there are a few little things like that…I might have to do an addendum for the paperback [laughs].”

Use arrow keys to turn pages (page 1/3)

Was it a conscious decision to focus more on the making of Unknown Pleasures than Closer?

“Closer is in there, but don’t forget that Closer was right at the end of the Joy Division – we finished it in March and he [Ian Curtis] was dead in May. We never got to play Closer, we never got to focus on it in the way we focussed on Unknown Pleasures as a band. The band was over then. The LP came out after Joy Division had finished. We never got to play the songs live.

“I have to admit that’s one of the great things about me playing the music again, as I’ve been doing this past year. I finally got to play those songs. That was nice, to get that back. I suppose in a funny way it’s like me clearing out my metaphysical loft. I’ve cleared it all up, made a list of it all, and it’s lot tidier than when I first went in [laughs].”

“If you were a new musician now, you’d be looking at all these old twats and going, ‘Fuckin’ ‘ell….we’re never gonna get rid of these bastards!'”

Does it feel strange to be at the centre of this kind of heritage culture that has arisen out of Factory, The Hacienda, Joy Division, etc?

Does it feel strange to be at the centre of this kind of heritage culture that has arisen out of Factory, The Hacienda, Joy Division, etc?

“Strangely, you get a lot of flak for it – I got a lot of flak for it when I opened Factory’s offices as a club. I got a lot of flak when I started doing the Joy Division music again, and I expect I’ll get a lot of flak for doing the fucking book. But the thing is that this year, in particular, if you look at the comeback of Stone Roses, Happy Mondays, Inspiral Carpets and bloody New Odour – you know what I mean? It ain’t going away, is it? So if you were a new musician now, you’d be looking at all these old twats and going, ‘Fuckin’ ‘ell….we’re never gonna get rid of these bastards!’ And I’m sure there’s a lot of people in Manchester feel like that, it’s like fuck, we’re always looking to the past with the Hacienda and all that!

“But the thing is, it was a great period. You know, it’s not like fucking Goodwood where we all dress up as 1930s characters or whatever… you go down, you play a few old tunes, you play a new tunes, you are of the moment. And that’s what people forget with with Fac 51 – it’s a young club full of young kids playing young music. All you’ve done is give them somewhere good to go, that was inspired by the past. But people lump you in that category, don’t they? You know, you’re a heritage act, you’re all about the past, and it isn’t true – it’s just them being cynical. I mean, look at what I’m doing. I’m in the business of music and I have been for 32 years, and any kind of music I will be involved in – and even when I DJ, I play a lot of new music. But people never focus on that, do they? They always want to have a cheap shot, don’t they? [laughs]. It’s unfortunate, but you do get used to it.”

“What surprised me most about playing Joy Division music was the bile that came from the rest of the band.”

So you’re aware of a certain hostility towards you?

“What surprised me most about playing Joy Division music was the bile that came from the rest of the band – that really shocked me. Because they’d been playing Joy Division, with Bad Lieutenant, before me. And they said what I was doing was disgusting! And that really shocked me. It’s like when you’ve been with someone for that long and then all of a sudden you realise you don’t fucking know ’em, at all. So I did find that very disheartening. And I think that their reaction to the book has been that I’m going to stitch them up in it, which isn’t true – I never set out to do that.”

Use arrow keys to turn pages (page 2/3)

Obviously in most books, films and documentaries there’s been a tendency to focus on the tragic arc of the Joy Division story; everything points towards Ian’s death. Was being in Joy Division, at least in the early days, a more carefree experience than these accounts suggest?

“The great thing about your memory is that you tend to remember things being quite a bit better, if not a lot better, than they actually were [laughs]. I do remember that whatever success we had, whatever achievement we were celebrating, we were always very worried about Ian. It did have an effect on you. Every plaudit that you got, you were thinking shit, I hope Ian’s alright. It was always in your mind. And seeing it all written down was pretty disconcerting, actually. Because you see how intense it was. You know, he did his self-harming episode and then we were literally gigging the day after. Nowadays you wouldn’t fucking do that, would you? You know, if fucking Gary Barlow started cutting himself up before a Take That show, you wouldn’t say, oh, he’ll be alright in the morning, let’s just get him to the gig – he’d have fucking six months off!

“If fucking Gary Barlow started cutting himself up before a Take That show, you wouldn’t say, oh, he’ll be alright in the morning, let’s just get him to the gig.”

“You definitely had to be made of tougher stuff then than you do now, but it is hard to look at the intensity of it and say that what we did was right. Hindsight’s a wonderful thing, isn’t it? A wonderful thing that you only get afterwards when you can’t do a fucking thing about it.

“You definitely had to be made of tougher stuff then than you do now, but it is hard to look at the intensity of it and say that what we did was right. Hindsight’s a wonderful thing, isn’t it? A wonderful thing that you only get afterwards when you can’t do a fucking thing about it.

“What I loved about Ian was that he was a great friend, and a great colleague. He was very, very generous and he was very open to making sure that you were as well-represented in what you were doing as he was. And a lot of musicians aren’t like that. A lot of musicians are very much out for themselves and don’t give a fuck about anybody else. So I really admired that about Ian. His attitude to the group was that we were all in this together. I remember how annoyed he was when someone called us ‘Ian Curtis & Joy Division’. He literally got on the phone to this geezer and went fucking mental – I should’ve put this in the book, actually – saying, ‘It’s not fucking “Ian Curtis & Joy Division”, I’m a part of Joy Division.’ He really hated himself being singled out, he was really very fair and very equal in the way that he viewed the band.”

“Ian really hated himself being singled out, he was very fair and very equal in the way that he viewed the band.”

Now that you’ve tidied up this corner of your metaphysical loft, what’s next?

“Well, concentrating on the Joy Division stuff has really stopped me doing new music. And I was actually reading an interview with Bernard yesterday, where he was saying that New Order – and I don’t think they are fucking New Order mate, more like some pale fucking imitation of New Order [laughs] – are going to do another LP. And I thought shit, I could do one. As a musician, I was taught by Rob Gretton and Tony Wilson that the best song you are ever going to write is your next one, so you’ve got to get on with it – so regardless of how many copies you sell, you do need to satisfy yourself creatively. I’ve got a project called Man Ray, it’s on Hacienda Records – I’ve been writing a lot of music with a partner of mine called Phil Murphy, which is really fun. We’re not trying to be commercial, we’re relaxed about it, it’s quite soundtracky, which is nice – you don’t have to come up with a killer fucking chorus, or a killer verse, like you do normally. So that’s actually quite relaxing. But yeah, now that I’m not in New Order, I could do with a job – maybe you could run an ad for me?”