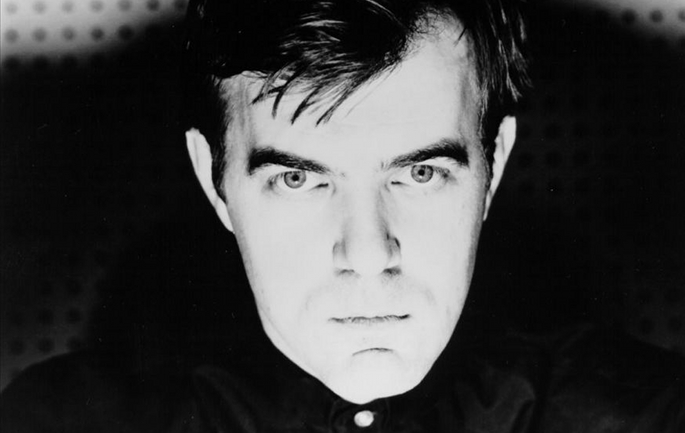

On the eve of the release of his first album in a decade, Back To Mono, FACT talks to noise pioneer, artist, author and self-proclaimed leader of the Church of Satan, Boyd Rice.

“I don’t know if you read my statement…? You can look it up. See what you think. . . “

In the back offices of a cinema in the centre of Paris, the previously jovial, effusive Boyd Rice has suddenly adopted a hushed sotto voce. The “statement” he is referring to was issued in 2010 on Rice’s website. In it he announced himself to be Anton LaVey’s successor as leader of the Church of Satan and promptly declared that the organisation “no longer exists”.

“I’ll just say that it’s very true and I stand behind it. And it wasn’t meant to be ironic or paradoxical. People in the Church of Satan are saying this is tongue in cheek. I’ll surprise you.”

By Rice’s account, Anton LaVey, the Chicago boy who ran away to join the circus before turning his line in carny hucksterism into an individualist cult of carnal indulgence, repeatedly pressed him to assume the mantle of high priest but Boyd refused. “I’m not a leader,” he avers, “I’m not an organisation type man.” So instead LaVey announced the creation of a Council of Nine to take over Church operations upon his death, and made Rice a member.

So, I ask tentatively, what does being in the Council of Nine entail exactly?

So, I ask tentatively, what does being in the Council of Nine entail exactly?

“Absolutely nothing.” And with that the spell is broken and Rice erupts into sudden uproarious laughter. “Nobody ever asked me for my opinion. Nobody ever called me up and said, uh, Boyd, do you think we have too many pinheads in the organisation that are dressed in black and going around saying ‘hail Satan’ all the time? Because, you know, I would have weighed in on that. . .”

I met Boyd Rice at a festival of weird cinema at the Forum des Images in Les Halles. Dressed all in black with a Maltese cross on his chest (Rice has a website dedicated to research into grail mythology) and a biker’s cap by his side, he exudes at all times an easy boisterous charm: laughing at my jokes, even complimenting at length my little digital recording device. Later that night, he would perform a live soundtrack to the 1955 cult film, Dementia – one of the Incredibly Strange Films in the RE/Search volume Rice edited with Jim Morton – so we’d been talking exploitation b-movies and the ‘mondo’ films of Gualtiero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi.

Rice with Anton LaVey

Rice with Anton LaVey

Would you say you were drawn to extremes in all things? I ask.

“Probably,” he replies. “Probably things that people would call extreme. I don’t know if I would call any of these things extreme.”

In the 1970s, Rice was one of the first musicians outside the academic avant-garde to pioneer a whole cluster of techniques that would prove cardinal to the nascent noise, industrial and electronic music scenes. He has credited himself with making “sample-based music about a decade before the advent of samplers”. From his earliest recordings as NON, he was experimenting with locked grooves and records with multiple holes which encouraged listeners to play them at any speed they chose. Intriguingly, he claims such experiments preceded any knowledge of a history of turntable manipulation by composers such as Pierre Schaeffer and John Cage. The avant-garde legitimation comes later.

“When I was a kid I would play records off-centre,” he says, “I would play them at all different speeds, and make the Shangri-Las sound like a group of gay men.” This elicits a fulsome laugh from Rice. “And then, I was very much struck by a quote by John Cage where he said, I don’t like making records because records are too fixed a medium. So that brought back my childhood memories and I thought: nothing’s fixed. At that point I just thought, I want to release a record that can be played at four speeds; I want to release a record with a second hole in it so people will be forced to play it off-centre. And then coming up with the locked groove was sort of an obvious next step.”

“When I was a kid I would play records off-centre,” he says, “I would play them at all different speeds, and make the Shangri-Las sound like a group of gay men.” This elicits a fulsome laugh from Rice. “And then, I was very much struck by a quote by John Cage where he said, I don’t like making records because records are too fixed a medium. So that brought back my childhood memories and I thought: nothing’s fixed. At that point I just thought, I want to release a record that can be played at four speeds; I want to release a record with a second hole in it so people will be forced to play it off-centre. And then coming up with the locked groove was sort of an obvious next step.”

Use your keyboard’s arrow keys or hit the prev / next arrows on your screen to turn pages (page 1/4)

Much as, earlier, he had told me the appeal he found in exploitation films while growing up was more visceral than intellectual, so here the origin of his phonographic experiments is ludic, an element of childhood play. But Rice remains sceptical of the ease with which experimental-sounding records can be achieved with modern technology.

“I think this overabundance of technology has actually made it less interesting,” he claims. “When I started out, there wasn’t a genre called ‘noise music’. If I wanted to try and get that effect, I had to try and think of how to do it and I’d have to come up with something creative. Whereas now I think everybody can just press a few buttons and get something in a few seconds that took me hours to do thirty-three years ago. [That] makes it easier for a lot of lazy people who wouldn’t actually sit down and apply themselves to something.”

And how has that changed what you do with sound?

“Well, immensely – for a while. Because when I started out, nobody else was doing just absolute noise music. Throbbing Gristle were noisy. There were some bands that were noisy. But there weren’t people that were doing absolute full on noise. So when the market became flooded, I thought, well, how can I change this up so I differentiate myself from all these other people; so that people hear this and they go, oh that’s Boyd – nobody else would’ve done something like this. So I think that’s what I’ve been doing for – I don’t know how many years…”

“Well, immensely – for a while. Because when I started out, nobody else was doing just absolute noise music. Throbbing Gristle were noisy. There were some bands that were noisy. But there weren’t people that were doing absolute full on noise. So when the market became flooded, I thought, well, how can I change this up so I differentiate myself from all these other people; so that people hear this and they go, oh that’s Boyd – nobody else would’ve done something like this. So I think that’s what I’ve been doing for – I don’t know how many years…”

Hence, today, Back to Mono: an album which returns to first principles, even including a few covers and reprisals of old favourites. “I thought, ok, I shouldn’t punish myself because there are a bunch of mediocre noise bands. I still love noise, I want to do something noisy again. And: can I still do it?”

Though Rice is comfortable comparing himself to Jackson Pollock and Marcel Duchamp and aligning his music within a history of fine art (“I think it can fit in there”), he also sees what he does as something useful, somehow functional. He has written extensively in the past about functional musics like Muzak and, with record titles like Easy Listening for the Hard of Hearing and Pagan Muzak, it’s unsurprising that he sees little to separate avant-garde noise from these more utilitarian sounds. Noise can “regulate your metabolism” he says; it can be “soothing”.

But as much as a balm, noise can also be a line of defence. “If you’re in your living room and somebody’s outside with a leaf-blower, and you just hear this thing going -” and here he imitates the rising and falling fuzz tone of a leaf blower “- If you put on something noisy and droney and turn it up full blast, it’s almost as though you’re creating an artificial silence because it’s so loud you can’t hear the other irregular, uneven noises which tend to grate on your nerves. Or like a baby outside. There’s been a baby outside in somebody’s backyard recently…”

Use your keyboard’s arrow keys or hit the prev / next arrows on your screen to turn pages (page 2/4)

For Rice, his own music can be a sort of weapon – he is well known for using means of psychological torture upon his own audiences – but equally a line of defence against the world, against the intruding sounds of his neighbours. Music and misanthropy, as in the title of Boyd’s 1990 album with “friends” including former National Front member Tony Wakeford, are here inseparable.

Later he will tell me about a song on his 1996 collaboration with Death in June, Scorpion Wind, whose lyrics he describes as a “generalised thing about inequality and the barbarity of human beings.” He continues, comparing the song to Orson Welles’s famous soliloquy in The Third Man, “It’s like three people imagining this vision of the world and how it’s, like, just insects fighting.”

Later he will tell me about a song on his 1996 collaboration with Death in June, Scorpion Wind, whose lyrics he describes as a “generalised thing about inequality and the barbarity of human beings.” He continues, comparing the song to Orson Welles’s famous soliloquy in The Third Man, “It’s like three people imagining this vision of the world and how it’s, like, just insects fighting.”

“Only these lyrics were not written by Welles or Graham Greene, nor even by Rice himself.They are taken verbatim from a text by Arthur de Gobineau, the 19th century French aristocrat whose Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races would become notorious for having developed the theory of the Aryan master race, later to inspire Adolf Hitler.

“I love Arthur de Gobineau!” Rice brags exuberantly, though admitting, “I’ve never read de Gobineau in his entirety.” Still, “Artie” de Gobineau is thanked on the sleeve of Music, Martinis & Misanthropy and his Selected Political Writings are featured prominently on a “recommended reading list” on Rice’s website. “I don’t think that to believe in the principle of natural inequality that necessarily equates to: you hate black people or you hate Jews or something,” Rice insists. “I think most people, their knee-jerk reaction would be to say, oh if he’s talking about natural inequality what he’s really saying is – ”

“I love Arthur de Gobineau!” Rice brags exuberantly, though admitting, “I’ve never read de Gobineau in his entirety.” Still, “Artie” de Gobineau is thanked on the sleeve of Music, Martinis & Misanthropy and his Selected Political Writings are featured prominently on a “recommended reading list” on Rice’s website. “I don’t think that to believe in the principle of natural inequality that necessarily equates to: you hate black people or you hate Jews or something,” Rice insists. “I think most people, their knee-jerk reaction would be to say, oh if he’s talking about natural inequality what he’s really saying is – ”

But what do you mean by “natural inequality”? I interrupt.

“Just that, um, you know. That not everybody is my equal, and I don’t expect them to be. It’s like, you can’t find two dogs that are equal. Now, if you could go down to amoebas, they’re much more the same. But as you progress up the evolutionary scale, things become more and more ‘inequal’, until you get to human beings.”

Daniel Trilling, the author of a recent book about the British far right (Bloody Nasty People: The Rise of Britain’s Far Right), confirms that such ideas about natural inequality justified by a spurious evolutionary theory fit very neatly within the history of twentieth century fascist thought. And when you start to look a little further down Rice’s reading list, you find a cavalcade of fascist ideologues, from Alfred Rosenberg, the Reich Minister for the Occupied Eastern Territories, found guilty at Nuremberg of war crimes and crimes against humanity; to Julius Evola, the anti-semitic esotericist who had a major influence on the British National Front in the 1980s when it was under Nick Griffin’s leadership.

“I have no political beliefs,” Rice claims, because politicians are all “dissimulators” (Trilling attests that this kind of glib dismissal of mainstream politicians as all the same is a common campaigning tactic amongst BNP and English Defence League foot soldiers). But this desire to raise himself above the grubby business of politics is just another aspect of Rice’s general contempt for humanity – something he traces back, like his love for trash cinema and penchant for experimental phonography, to his childhood. “I’ve always been somewhat of an elitist as well,” he admits, “Because even as a child I was a weirdo. I was a little different. And I just always felt that I could see what was going on and most people couldn’t. So I always felt a little apart from everybody else.”

“I have no political beliefs,” Rice claims, because politicians are all “dissimulators” (Trilling attests that this kind of glib dismissal of mainstream politicians as all the same is a common campaigning tactic amongst BNP and English Defence League foot soldiers). But this desire to raise himself above the grubby business of politics is just another aspect of Rice’s general contempt for humanity – something he traces back, like his love for trash cinema and penchant for experimental phonography, to his childhood. “I’ve always been somewhat of an elitist as well,” he admits, “Because even as a child I was a weirdo. I was a little different. And I just always felt that I could see what was going on and most people couldn’t. So I always felt a little apart from everybody else.”

And how did your family react to that?

“My mother thought I was the greatest person on Earth. My father thought I was going to drive him insane.” According to a Post-Punk Memoir by Lisa Crystal Carver, the mother of Boyd’s son, Wolfgang, Rice’s own father was an avid consumer of amphetamines, prone to paranoid fantasies about the CIA planting bugs in their family home. He would spend the night disassembling every appliance in the house, looking for phantom surveillance equipment.

Use your keyboard’s arrow keys or hit the prev / next arrows on your screen to turn pages (page 3/4)

Still, Rice’s professed aversion to politics is difficult to square with a number of occasions when he has explicitly promoted political views of the most unsavoury kind. In 1989, Rice posed for short-lived U.S. teen magazine Sassy with Bob Heick, founder of white supremacist group, the American Front, wearing AF uniforms. “I was never a member of that group,” Rice insists “But [Heick] said, we need as many groovy looking people as we can get. It turned out to be inclement weather so all these other Aryan warriors didn’t show up. So I was the only guy who showed up.” Still, against Rice’s defenders who will persistently claim he is just an arch-provocateur, he was clear in telling me, “That wasn’t meant to wind anybody up.” He paints it, rather, as something he did simply for the promise of free beer.

One wonders how much free beer was promised for Rice to appear, at around the same time in the late eighties, on a public access cable TV show called ‘Race and Reason’ hosted by Tom Metzger, founder of the activist group, White Aryan Resistance, and former Ku Klux Klan ‘grand dragon’ for the state of California. Here Rice includes himself and former collaborators Death in June and Current 93 as artists who are either “racialist oriented” or “moving more and more towards racialist stuff.” Metzger and co-host Tom Padgett suggest that electronic music is “intrinsically white” and that it doesn’t “play on the same wavelength as a lot of the, uh, minorities” and Rice nods sagely, “Yeah, that’s what I feel too.” Metzger even goes so far as to suggest that Rice and his friends could be spearheading “a new propaganda art form for white Aryans.”

“Yeah, yeah, I think so,” confirms Rice, adding that he believes “this music appeals to a certain core of people. There are people everywhere who feel not a part of anything else that’s going on around them.” Much as he said to me of himself.

“Yeah, yeah, I think so,” confirms Rice, adding that he believes “this music appeals to a certain core of people. There are people everywhere who feel not a part of anything else that’s going on around them.” Much as he said to me of himself.

It was around that time that Rice worked as a nightwatchman for a group of apartment buildings in San Francisco, patrolling from eleven at night to seven in the morning with a gun and a pair of handcuffs, waiting for an alarm to go off. In the course of the job, which is documented in his recent book, Twilight Man, Rice found himself exposed to “this whole apocalyptic side of San Francisco that most people weren’t. In the course of the book you can kind of see how I got into the mindset that I was in in the eighties because I just saw weirdness and violence and ugliness on a weekly basis. I really got to the point where I was in this Travis Bickle mindset. Driving through the streets of San Francisco just scowling at it all: at the people vomiting blood into the gutter, and the people taking a shit on the sidewalk.” He laughs at this as he tells me about it.

“Every once in a while it gets annoying to still hear about” some of the more controversial moments of his past, Boyd tells me. He struggles with his self-made image as a “professional asshole” even as his insistence that he puts a “premium on civility” is hard to square with some of the things he has said and some of the company he has kept. Still, unlike Tony Wakeford of Death in June and Sol Invictus, who in 2007 renounced his NF membership as “probably the worst decision of my life”, Rice remains unrepentant. “No,” he says, pausing dramatically for a quick hoof of snuff, “I don’t regret anything I’ve ever done.”

Use your keyboard’s arrow keys or hit the prev / next arrows on your screen to turn pages (page 4/4)