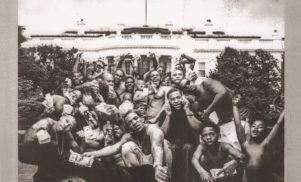

Available on: Top Dawg / Aftermath / Interscope

From the dusty sample that kicks off To Pimp A Butterfly — the hook from Boris Gardiner’s blaxploitation ballad ‘Every Nigger is a Star’ — Kendrick Lamar makes his intentions clear: this will not be a polite album, a comfortable ride, the soundtrack for a party. And why would it be? The last several years have been a reminder of America’s Big Lie: that a country built on the backs of slaves still hasn’t delivered on the promise of all men being created equal, not when cops and assorted vigilantes can murder black people without repercussion.

Where Lamar’s good kid, m.A.A.d city told the story of one man (a boy, really), To Pimp A Butterfly tells the story of a nation and a people, through the eyes of that same man. Calling the album “ambitious” doesn’t capture the order of magnitude with which Lamar has expanded his scope, as he moves from the singular to the plural without ever straying from the personal. For all his attacks of monolithic institutions — slavery, the police, the American political system — Lamar stays focused on the man in the mirror, confronting his own challenges and turning deep-seated fear, depression and self-loathing into self-love, self-knowledge, self-determination.

This isn’t a new message. It has been sung, shouted and spat for more than fifty years, by everyone from the struggle rapper on the corner to the pillars of black popular culture. It is the latter group that Lamar seems to be eying with To Pimp A Butterfly, trying his damndest to catapult himself into the pantheon of black power music next to John Coltrane, James Brown, Sly Stone, Public Enemy, the Native Tongues collective and (most notably) Tupac Shakur.

Often, he does this literally: enlisting George Clinton, Ronald Isley and the voice of Tupac, legends unafraid to broadcast their politics through their music. But mostly, the references are stylistic, as the album forgoes the often club- and radio-ready sounds of good Kid for a synthesis of cafe-born jazz, psychedelic soul, electric blue funk and boom-bap hip-hop. The album kicks off with the G-funk of ‘Wesley’s Theory’ and the P-funk of ‘King Kunta’, the jazz calamity of ‘For Free?’ and the soulful soothsaying of ‘Institutionalized’, mostly sticking to those rivers and lakes for the remainder.

It’s the same palette favored by a generation of neo-soul and indie hip-hop artists, and one that has fallen out of favor in popular rap circles and has mostly been ghettoized as the province of “conscious” rap. And while the merits, status and pigeonholing of conscious rap is a debate better held elsewhere, it is interesting to hear a rapper with one of the highest platforms and loudest megaphones in rap wrest control of a sound and style as he continues the throughline of funk and G-funk through the L.A. beat scene and back to mainstream rap.

Once the shock of the new (shock of the old?) wears off, To Pimp A Butterfly does not seem miles from good Kid: Lamar has always been uninterested in sounding like everyone else; he’s always been earnest and Christian; he’s always rapped his ass off. His gift for changing his voice and his flow to portray different characters, moods and messages is intact: on ‘u’, his voice gets progressively more strained as self-hatred takes its toll.

But whereas good Kid used poetry to further a narrative, To Pimp A Butterfly uses poetry… as poetry. Lamar’s lines are heavy with metaphors and images that invoke slavery, black history and black bodies in general: double entendres about whips and chains, skin color, facial features and, yes, dick size (lest we forget, Kunta Kinte chose amputation of his foot over castration). There are lines that recall Malcolm X in the window and Black Panthers patrolling the streets; “I made a flower for you out of cotton” is reminiscent of Tupac’s The Rose That Grew from Concrete.

And forget his comments in the press that veered a bit close to victim-blaming. Lamar is anything but blind to systemic racism, but it seems that he sees personal responsibility and self-love as the last vestige of control in a fucked up world. To Pimp A Butterfly ends with the poem that Lamar has been teasing for the entire album, telling the tale of his hero’s journey into the world as he returns home, full of love and respect for his neighbors; it’s the only way they’ll be able to survive. (For an album that has been described as difficult to digest, the messages are presented pretty plainly.)

What follows is an imagined conversation with Tupac, a literal communion with a spectre that looms large over the entire project (and for rappers of Lamar’s age, all of hip-hop). Tupac was the master of the balancing act that Lamar is attempting, between poet and rapper, political and commercial, self-loving and self-loathing. Twenty years on, his words still ring true; class and race struggles in America haven’t changed that much, even if rap certainly has.

In just a week, To Pimp A Butterfly has quickly been mired in the world of hot takes and “classic or nah” arguments. Is it too dense, too political, too throwback, too rapping-ass-rapping to move the dial? Those conversations should just be starting, not finishing. This is the type of album on which everyone will have an opinion that they better be ready to back up.

The case of lead single ‘i’ is instructive. While it was initially dismissed as corny (or worse), the song has been revamped for To Pimp A Butterfly as a pseudo-live rendition that contrasts “I love myself” with “I put a bullet in the back of the back of the head of the police.” It’s still over that legendary Isley Brother sample, but now its message of black self love is even more strident, especially when juxtaposed to companion track ‘u’. On songs like ‘i’, ‘Blacker The Berry’ and ‘King Kunta’, Lamar is selling revolutionary ideas with a song and dance, in a medium that delivers the message. It may be the most important lesson he’s learned from Tupac.