Justin Vernon returns this week with 22, A Million, a collection of sample-driven tracks written while battling depression after an aborted soul-searching trip to the Greek island Santorini. Al Horner heads to Vernon’s hometown of Eau Claire, Wisconsin to hear how what could have been a Greek tragedy ended up an exciting new electronic dawn for Bon Iver.

If the defining mental image of Bon Iver till now has been of a melancholy man alone in the woods, 22, A Million is the sound of that man disappearing deeper into the trees, even further from prying eyes. “I don’t do well with things like that,” insists Justin Vernon, dressed down in Timberwolves hat and Les Mis tee, describing his struggle to pose for fan photos and the glare of life in the spotlight. 2011’s Grammy-winning Bon Iver, Bon Iver – released between high profile work on Kanye West’s Twisted Fantasy and Yeezus records – was a grand, autumnal indie epic that saw his unlikely celebrity status peak. All of a sudden, “some fucking dude from Wisconsin” (his words) was the subject of Justin Timberlake skits on Saturday Night Live and packing out arenas worldwide. In the few interviews he’s done in the years since, he’s given the impression of that relative fame tiring him, dreaming aloud to journalists about quitting music to open a breakfast cafe and “winding down” Bon Iver forever.

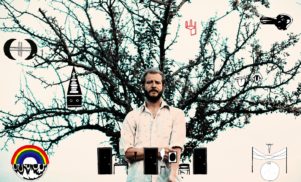

All of which makes you wonder if there’s an ulterior motive to the obscure sound (and even more obscure track titles) of his challenging third album. Vernon’s career exploded in 2007 with the campfire lullabies of For Emma Forever Ago – a creaky folk classic recorded in his father’s remote hunting cabin, having retreated from the world after a breakup. Almost a decade on, it sounds in the seldom interviews he now gives like he longs to escape again, or at least shake off some of the spotlight. “I have more recognition than I ever wanted to deal with,” he recently told The New York Times, explaining he’d taken his face out of all press shots for the new album because being constantly photographed over the last few years left him feeling “very exposed, with scarred skin from the whole experience. Not that it was all bad, but it wore down these outer layers, and everything kind of hurt.”

The sense of Vernon taking himself out of plain view on 22, A Million isn’t limited to the album’s faceless artwork. Inspired by cult Californian Richard Buckner, civil rights-era singer Bernice Johnson Reagon and “new toys in the studio”, it swaps out his traditional honeycomb heartbreak and acoustic confessionals for rough samples that jutter in and out of tracks.

Elsewhere, manipulated saxophones descend into discordant madness (‘21 M♢♢N WATER’), and Vernon’s Auto-Tuned vocals cross-stitch half-sentences and invented words (shout out “fuckified”) more impressionistically than before, leaving dreamy lyrical vapour trails across his music. It’s five tracks before you hit a song – the gorgeous ‘29 #Strafford APTS’ – that features really prominent guitar, an instrument that till now has always felt one of Vernon’s driving forces. The result is Bon Iver’s most ambitious and arresting album to date, but the one on which Vernon feels the most veiled.

Bon Iver’s old sound didn’t exactly chase mainstream embrace, but their new one seems to actively dart away from it. “I went looking for new sparks,” admits Vernon, speaking at a press conference in his hometown Eau Claire (instead of “sitting in hotel rooms in front of journalists” for the next few months “answering the same questions again and again”, he’s invited 20-or-so writers from around the world to give the world media his story out in one go). He was after an aesthetic, he says, that was “broken down and messed up. Because personally, with what I’d gone through and what other people I knew had gone through, I wanted to break down and crush something and do something aggressive sounding.” Which might explain the rumbling electronic pulse of ’10 d E A T h b R E a s T ⊠ ⊠’, the bit-crunched percussion and the deep bass of ’33 “GOD”‘, and many other moments on a record he describes as “more shouty” compared to his “whispering” of old.

Early on in the making of the album, Vernon suffered a spell he’s taken to calling “the European horribleness” – a trip to Santorini that saw him suffer anxiety attacks and paranoia. “Don’t go the Greek islands off season by yourself,” he laughs. “I was trying to find myself. Eurgh. I did not. I was incredibly bored, panicking a lot, walking around this town for a week by the ocean. I felt really poor at that time.”

Two albums into his career as Bon Iver, he’d hit a wall, unsure how to move it forward without lurching into the self-parody – the sadsack indie troubadour who in Timberlake’s SNL parody fashions a guitar out of a canoe while on a barefoot ramble. “Being sad about something is okay. But then wallowing in it, circling around the same cycles emotionally just feels boring. I needed to sound a little radical to feel good about putting something out into the world.”

Which is how a tiny white box the size of a pencil case became one of the driving instruments on 22, A Million. The TE OP-1 is a tiny sampler that Vernon found allowed him to experiment with ideas on the fly, recording hummed melodies and manipulating them till something leapt out. “A lot of moments on the record came from using that particular instrument,” he says. Its opening track is one of them, and started life on that failed Santorini trip. “I just heard this chorus in my head, one line.” He found himself humming one phrase on repeat: “It might be over soon”. “When I got back I sang some improvisation into the OP-1,” he remembers, falling in love with its “duality, like a paradox, a two-sides-of-the-coin thing.”

“It might be over soon” can sound like optimism that a pain or sadness may go away. But just as easily, it could mean that something beautiful is approaching its end. The first single, and blueprint for the rest of the record, ’22 (OVER S∞∞N)’, was born. After this breakthrough, “it wasn’t seeming very obvious to me anymore to pick up a guitar as often,” he says, describing the OP-1 having established a different “language” to the album that guitars didn’t fit into so neatly. “It wasn’t as fun or as easy and it took a longer time than I’d have liked, but that instrument in particular and other tools in the studio helped me to mess things up.” Where previous Bon Iver records felt like songs written and then recorded and produced, 22, A Million has the densely textured feel of a record on which production became crossed a frontier, becoming a part of the actual songwriting. “It was about setting up new toys and setting up zones, and trying not to get stuck in any technological toilet bowl,” he says.

Though much has changed for Bon Iver since his last outing five years ago, much remains the same. Even if they’re framed differently, by an increasingly electronic palette of sounds, it’s still wistfulness and romance that drive Vernon’s music. “Well, I’ve been carved in a fire,” he repeats on ‘_____45______’, a moment of sweetness that’d be called gospel, were its subtle organs not swamped in wild swelling saxophone harmonies created on a piece of software specially invented for the album, the Messina (named after engineer and close collaborator Chris Messina). “The older you get, the more aware you become of how minute our existence is. There’s this Louis CK quote I like: “It’s not your life. It’s just life.” I like that,” Vernon laughs. His point is to embrace and be humbled by the randomness of life, to lose yourself in it. After all – it might be over soon.

Al Horner is on Twitter.