We’re at the stage in history where using music software isn’t so much an option as it is a necessity.

Sure, there are always going to be some contrarian sorts who take it upon themselves to record to dictaphone tape and pen their sheet music on rolls of dried human flesh, but nowadays they’re in the minority. If you’re going to be recording music, chances are you’re going to need some software to do it, and there are plenty of options.

It wasn’t always this way – back in the early ’80s, when the MIDI (musical instrument digital interface) protocol was in its infancy, computers were still glorified word processors, and while some brave souls were attempting to generate experimental sounds (Max Mathews, please stand up), most of us were simply stuck waiting half an hour just to load a copy of 3D Monster Maze, only to be met by a read error at line 348.

Over time, however, music software blossomed, and transitioned from fiddly time wasters, doomed to the forgotten directories on an Commodore Amiga cover disk, to the plethora of usable and sturdy apps we have available to use today. It wasn’t long before software actually started to surpass most hardware, and for all the times you hear Jack White harping on about dubbing to two inch tape, it’s far more convenient to just boot up your shareware (read: free) copy of Reaper and simply hit record.

In 2014, you can even make music on your phone – with software that would put a decrepit copy of Opcode Vision to shame – but those old programs that many of us had to plough through, crash after crash, were absolutely crucial in informing not only the digital audio workstations and suites of plug-ins that we have available to us now, but also the music itself. Can you really imagine how Chicago drill would sound without FL Studio? How quiet music might still be without L1 Ultramaximizer, or how T-Pain might sound without Autotune?

The following programs changed the way we think about the relationship between music and software, for better and for worse.

Performer (1985)

One of the very earliest commercial software sequencers – and certainly the first for Apple’s Macintosh system – was Performer, from Massachusetts-based software company Mark of the Unicorn (MOTU for short). It was released only two years after the introduction of MIDI, the protocol that enabled computers (and other hardware) to communicate with a growing arsenal of compatible synthesizers, samplers and drum machines, and worked as a bridge between the computer and a studio’s worth of gear. Even better, Performer allowed producers to dig deeper into the hidden features in their shiny boxes – notoriously difficult-to-program synthesizers such as the Yamaha DX7, which previously were only patchable using a clunky LCD display, were now open to be controlled by a far friendlier system.

Five years after its original release, the sequencer’s advanced MIDI capabilities were bolstered by a hard disk recording option, and the program was renamed Digital Performer, a name it retains to this day. Initially, the program was backed up by a physical add-on – MOTU’s legendary hardware is still revered to this day – but over time, and as personal computers were blessed with the advanced processing power we take for granted today, the external elements became less important.

What does it do?

Performer was a way to visually compose and sequence tracks using electronic instruments, something which back in 1985 was still an incredibly novel idea. When Digital Performer was released however, we began to see the emergence of something else entirely – the digital audio workstation, or DAW. It’s tough in 2014 to recall a time when some kind of visual composition and production tool wasn’t the norm, but Digital Performer helped set the stage for much of what was to come, and did it with the kind of rock-solid, industrial-strength power that is still spoken about in hushed tones.

Who used it?

Digital Performer’s versatility and its complex MIDI functionality has seen it championed by a certain tech-obsessed subset of electronic musicians, and rightly so. Warp veterans and noted gear obsessives Autechre are paid-up members of the fan club (Sean Booth mentioned in a 2008 interview that it would be a copy of Digital Performer and a microphone that he’d take with him if he was locked in a jail cell for a year and allowed one piece of equipment), and so are Björk collaborators Matmos, who have been using the sequencer since way back in 1987. The BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop were also spotted using one at various points throughout the 1980s, and synth innovator Wendy Carlos has called it “the one essential piece of software ‘equipment’.”

Heard on:

Weird Al Yankovic & Wendy Carlos – ‘Carnival of the Animals – Part II’ (1988)

Matmos – ‘California Rhinoplasty’ (2001)

Autechre – ‘6IE.CR’ (2003)

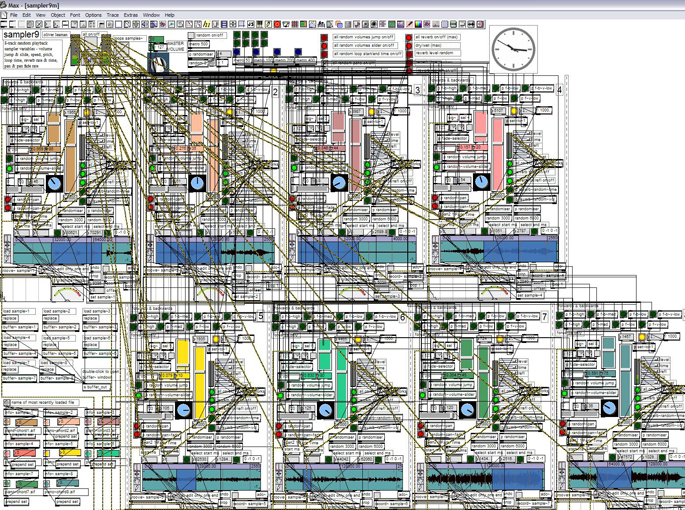

Max (1986)

Max was developed in the early ’80s by American music professor Miller Puckette while he was studying at French electro-acoustic music institute IRCAM, and was intended to be a “computer environment for realizing works of live electronic music.” It was based on ideas from Max Mathews (who also lent Max its name), developer of the massively influential MUSIC (the first computer program to generate audio waveforms through synthesis) and Barry Vercoe (developer of MUSIC 11, and eventually Csound) but unexpectedly began to attract attention from users outside of the academic circle.

What helped take Max beyond the confines of the lab was the involvement of the tireless David Zicarelli, who commercialized the software with help from Opcode Systems (the developers of Vision, another competing sequencer) and began to sell it in 1990. Guided by Puckette’s powerful new program Pure Data, Zicarelli evolved Max into Max/MSP (which either stands for Max Signal Processing or Miller S. Puckette depending on who you talk to), which introduced revolutionary real-time audio processing.

In 1997, Zicarelli started Cycling ’74, who since 1999 have handled all of Max’s commercial packages. Max has since seen the addition of a video manipulation package (Jitter), a plug-in bundle (Pluggo) and been integrated with popular DAW Ableton Live, and continues to grow in popularity.

What does it do?

Potentially, Max can be engineered to do pretty much whatever you need, providing you have the chops to program it. It’s used to control installations, to process instruments on the fly, as a live performance tool, as a sound generator and even to generate complete musical compositions. A patch-based system (similar in many ways to an old modular synthesizer), its graphic user interface allows users a slightly more intuitive entry point into what, at its core, is a set of incredibly complex processes. If you want to build a synthesizer from scratch or simply make a 16-step sequencer to imitate the legendary Roland TR-808, then Max has you covered, and you’d still only be at the tip of the iceberg.

Who used it?

Initially used mostly by academics (particularly at IRCAM), Max was first used on stage in 1987 by experimental composers Thierry Lancino and Philippe Manoury. Manoury’s piece ‘Pluton’ is regarded as, in essence, the first Max patch, and can still be tracked down in various forms. Once Max began to gain traction in the outside world however, it was quickly championed by a throng of inquisitive electronic musicians.

Widely associated with the Austrian Mego label (which focused its efforts on “extreme computer music” in the mid-to-late ‘90s and early ‘00s), Max was put center stage by guitar abuser Fennesz while he developed his fiercely unique sound. Fennesz used the program more like an advanced guitar pedal, funneling his guitar sounds through the laptop to create sounds that would define a genre.

Keith Fullerton Whitman also used Max as a guitar processor, but eschewed bone-crunching noise in favor of billowing clouds of drone on 2002’s Playthroughs, an album which incidentally was named after a Max patch he’d been developing for some time (which itself was named after an obscure DSP status attribute). Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood was a fan too, throwing his riffs through Max to create a stutter that became a signature for a while.

Eccentric LA beatmaker Daedelus, on the other hand, put the software to use by constructing a series of sequencers which he controlled with the MonoMe controller, using it as an advanced sampler to reconstruct his fractured compositions. Autechre swam straight into Max’s generative side, and used the glassy, digital sounds as the basis for 2001’s Confield.

Heard on:

Philippe Maoury – ‘Pluton’ (1988)

Keith Fullerton Whitman – ‘Track3a (2waynice)’ (2002)

Radiohead – ‘Go To Sleep’ (2003)

OctaMED (1989)

Anyone who dabbled with music on the Commodore Amiga will likely still have a fondness for trackers. The term was coined after the appearance of 1987’s Ultimate Soundtracker, a music composition tool not a million miles away from the early sequencer bundled with the legendary Fairlight CMI workstation, and was applied to a plethora of similar programs that followed. Whilst nowadays DAWs all look fairly similar, tracker software dealt with composition in a very different manner – you wrote pieces of music by assigning values to steps on an array of tracks, which would scroll vertically rather than horizontally.

The software became popular in the growing “demoscene” – a group of programmers, electronic musicians and visual artists. In the pre-Soundcloud, pre-YouTube days, they would show off their work in short presentations that often ran before cracked versions of popular games and applications as a virtual tag to highlight the particular group’s skills on top of the cracking itself. The scene evolved to host large parties, where programmers and tracker aces would face off trying to stitch together the most economic, low usage patches that were technologically possible, and this is where MED (short for Music Editor) sought to be different. While most tracker software was trying desperately to pander to the needs of the nascent demoscene, MED was aimed squarely at musicians.

Usually the programs cut down on functionality to help lower CPU usage. MED, on the other hand, allowed for longer patterns and more complicated compositional structure, which pushed the usage to a point where the resulting file simply couldn’t be tacked onto the beginning of a game or demo. Thankfully, the extra features also caused the software to gain a legion of followers of its own.

In 1991, OctaMED was released, and could run eight separate channels on the Amiga’s notorious four-channel chip. It was popular and ubiquitous, and by 1996 supported hard disk audio recording and a massive 64 channels, before bowing out gracefully in the face of stiff competition.

What did it do?

OctaMED was a musical creation tool for budding electronic producers who were beginning to realize that you didn’t have to possess any traditional musical skills to put together tracks. In fact if you were using a tracker, it actually helped if you were more computer literate than you were able to read music or play a traditional musical instrument. The sequencing was intuitive and the creation method itself helped develop a sound that’s still cherished by fans today.

Who used it?

Because it was cheap, powerful and relatively easy to use, OctaMED was responsible for helping to shape the sound of early ’90s hardcore and drum’n’bass. Aphrodite used it considerably for his early run of 12”s, Rob Haigh (aka Omni Trio) used it to craft the majority of his influential full-length The Deepest Cut, DJ Zinc crafted one of the scene’s biggest breakouts – ‘Super Sharp Shooter’ – using it, and Urban Shakedown managed to get the humble, limited MED to cough out early jungle beater ‘Some Justice’. They managed to get around MED’s limitations in a particularly novel way, synching together two Amiga 500s by pressing the spacebar to reset the track until a series of clicks at the beginning matched up – it worked, and they were granted a hallowed eight tracks for their efforts.

Heard on:

Urban Shakedown – ‘Some Justice’ (1992)

Omni Trio – ‘Renegade Snares’ (1995)

DJ Zinc – ‘Super Sharp Shooter’ (1996)

Cubase (1991)

If one key sequencer has informed the direction of DAWs over the last three decades, it’s arguably Karl Steinberg and Manfred Rürup’s Cubase. It started life in the mid-1980s on the humble Commodore 64 under the guise of MIDI sequencer Pro 16. The weedy Commodore 64 didn’t come with a MIDI interface as standard so one was bundled with the software, and it wasn’t cheap. This all changed with the release of the Atari ST – a powerhouse at the time, and a computer that’s still considered the true musician’s choice. It was the inclusion of built in MIDI ports offering rock-solid timing that would rival today’s systems that made the ST so desirable amongst amateurs and pros alike, and Pro 16 was beefed up to Pro 24 to cater to the promising new system.

Cubit was released in 1989, again on the Atari ST, and introduced the world to what we would now recognize as a modern DAW. The program’s name, however, wasn’t long for this world – Cubit had already been snapped up and trademarked, so moments before the launch it was renamed Cubase, and it stuck. Over the next 20 years the software gradually grew into the powerhouse we know today. In 1991, Cubase Audio for the Apple Macintosh was released, and while it needed to be twinned with hardware to handle the audio elements, it acted as a precursor to the software that was to sit at the foundations of today’s system.

Cubase Audio for Windows came in 1995, and quickly adopted the acronym VST (virtual studio technology), heralding a new era of music recording. Now you could not only record audio directly to the hard disk drive of most mid-level home computers, but you were able to use a suite of effects that could modify the audio without the need for expensive outboard equipment. In 1999 Steinberg took the concept a step further, adding VST instruments – synthesizers and samplers that could be controlled from inside the sequencer without any further fiddling.

Further revisions added enhanced audio functionality and editing (the program was eventually merged with Nuendo), stability and audio warping, but the concept – a solid, relatively simple to use DAW – remains the same.

What does it do?

Cubase was the first piece of sequencer software to use an arrangement page that listed the tracks vertically and the timeline horizontally, something which actually changed the way people think about composing. While newer programs like FL Studio and Ableton Live offer different ways of manipulating and composing audio, each contemporary DAW still offers the now standard arrangement page, and it would be unlikely to see a new program lacking this feature.

It caught on primarily because it simplified the writing process immensely – you could now make MIDI phrases (and later audio) and drag them around the screen in small blocks, copying and pasting them as if they were words on a document.

Sadly, Cubase’s other claim to fame is less useful – the software was notorious for using outboard copy protection, known as a dongle. Even the first version of Pro 16 on the Commodore 64 was saddled with the dongle, which came attached to the bundled MIDI interface. Copy protection shouldn’t really be anything to complain about, but in the mid ‘00s the code was written into Cubase so heavy-handedly that it negatively impacted the program’s speed and stability, forcing many musicians to use the cracked version (which removed the bloat) if they actually wanted to use it professionally.

Who used it?

Cubase, in its many forms, was and still is extremely popular, especially in Europe. Early on, Tangerine Dream’s Edgar Froese was spotted using Pro 24, while Genesis’s Chester Thompson and Tony Banks were both early adopters of Cubase. Electronica innovators Mike Paradinas and Luke Vibert were fans, as were veterans Kraftwerk, Jean-Michel Jarre and big beat mastermind Norman Cook.

Glaswegian post-rockers Mogwai found an interesting way to shout out the program in 2001 when they bundled a Cubase session for the song ‘Hunted By A Freak’ with their album Happy Songs For Happy People. Encouraging fans to remix the track, they packed the session with the audio stems for the track, to allow Cubase users to import and start fiddling immediately.

Heard on:

µ-Ziq – ‘Brace Yourself (remix) (1998)

DNTEL – ‘Roll on’ (2007)

Hans Zimmer – ‘Time’ (2010)

Pro Tools (1991)

Still out of the reach of most home studios, Pro Tools has been staple for professionals since its debut in 1991. The program was developed by Evan Brooks and Peter Gotcher, USC graduates who were fascinated with E-MU’s Drumulator, an early sample-based drum machine. The two developers eventually started the company Digidrums to develop sample libraries that were offered on EPROM chips, but soon began to realize that users themselves might want the opportunity to record and edit their own sample sets without having to jump through hoops.

In those early days sounds had to be dubbed to a clunky videotape-based system, so Brooks and Gotcher put together a basic audio recording and editing package that they named Sound Designer. Their company was renamed Digidesign and in 1985 they released the sample editing tool that would become an industry standard, allowing the careful chopping of samples at a time when most producers were struggling with tiny screens and numeric values or dealing with presets and expensive expansions.

Sound Designer was still very limited, however, so in 1989 Brooks and Gotcher released Sound Tools, their first attempt at a full-featured digital recording package that offered far more flexibility than simple sample editing. Allowing full stereo recording and editing, Sound Tools was truly groundbreaking, and while it needed an expansion card (developed in house by Brooks) it offered something other software houses could only dream of.

Pro Tools followed in 1991 and pushed the concept even further, adding multitrack audio recording across four channels. Still reliant on hardware, Pro Tools succeeded where other platforms failed mainly because of its workmanlike TDM system, which allowed the bundled hardware to absorb the brunt of the processing power, allowing producers to stack effects without worrying about bringing their computer system to a halt. In the early ’90s this gave Digidesign the edge they needed, and while other DAWs have caught up since, Pro Tools has remained the professional’s choice, whether that’s still warranted or not.

A short-lived light edition (Pro Tools LE) was an attempt to reach the world’s bedroom studios, but at that point the market was already saturated with much better options, and Digidesign cut their losses and retreated to focus on what they’ve always been best at – professional studio software and hardware.

What does it do?

Since the software part of Pro Tools was initially simply a front-end for the powerful hardware setup, Pro Tools always allowed users to do a lot more with audio than they could with software offered by Digidesign’s competitors. The bundled effects were useful and sounded incredible, and as a mixing and mastering option it was pretty much unparalleled. However, there was a massive drawback – as DAWs such as Cubase and Logic added more complex and stable audio processing capabilities, Digidesign failed to bring their sequencing elements up to scratch, and Pro Tools has long lacked in the MIDI department.

Who used it?

While you might not be able to hear Pro Tools usage as easily as you could, say, OctaMED, it’s been used to record and mix countless mainstream recordings. There was a time when, if you wandered into a professional recording studio and someone was using a computer, chances are it was running Pro Tools – it was just that ubiquitous. As such it’s not hard to see why it’s championed by big name producers such as Timbaland, Just Blaze and Dr. Dre, who have all sung its praises at one time or another.

Pro Tools was also responsible for providing the world with its first number one record to be recorded completely within a hard disk system – Ricky Martin’s ‘Livin’ la Vida Loca’, which was produced by Desmond Child and Charles Dye.

More recently, Drake’s producer Noah ‘40’ Shebib used a Pro Tools LE setup to produce So Far Gone, and rapper/producer Big K.R.I.T uses it alongside Reason and ReCycle.

Heard on:

Ricky Martin – ‘Livin’ la Vida Loca’ (1999)

Justin Timberlake – ‘Sexyback’ (2006)

Drake – ‘Successful’ (2009)

Logic Pro (1993)

Logic, like most other DAWs, started life as another, simpler program. In 1985, C-Lab programmers Gerhard Lengeling and Chris Adams developed a MIDI sequencer for the Atari ST called Creator, and it quickly became an industry standard. Unlike Performer and Pro 16, Creator used pattern-based recording, meaning a producer could take sections of a song (the verse, chorus or introduction) and then layer them on top of each other and repeat as necessary. The system was similar to the hardware sequencers of the era, and Creator (which soon became known as Notator, with the addition of notation options) was widely used amongst a certain set of ST music producers.

In 1993, a number of developers split from C-Lab to form Emagic and put together a new cross-platform sequencer called Notator Logic. While it retained many of Notator’s key features, it was now blessed with an object-oriented arrange window, similar to the one pioneered by its competitor Cubase, and the program started to resemble the Logic we’re familiar with today. Eventually the Notator prefix was dropped, and Logic was ported to the Mac and PC platforms as the Atari ST started to die a slow and painful death.

Early on, audio recording was handled by the DAE (Digidesign Audio Engine) which had been licensed from the developers of Pro Tools, but this hardware reliant solution quickly fell out of favor as Logic grew to become a solid competitor to Cubase VST. By the time we reached Logic version 5 it had grown into a powerhouse, and included a bundle of plugins and instruments (provided you went for the Platinum edition) that would become ubiquitous – from the EXS Sampler to the excellent Multipressor – and featured an innovative “rubber band” style automation editor, which would quickly be cribbed by Logic’s peers.

In 2002, Apple bought Emagic and, much to the chagrin of PC users, discontinued the Windows version. Even so, the software has continued to grow in popularity (along with the Mac itself), and is now on its 10th iteration.

What does it do?

Logic was always intended to act as the workstation that bundled everything together, and what has long set it apart from direct competitor Cubase is a suite of plugins that actually sound as good (if not better) than the third party heavy hitters. Stable and surprisingly quick, Logic has a steeper learning curve than the other DAWs on offer, but is considered to be far more powerful for those that stick with it, and when Emagic introduced the new automation editor, it truly changed the way people interacted with sequencers.

Who used it?

Logic’s portability and the fact that it was jam-packed with features meant that it was incredibly popular with a huge variety of musicians. Radiohead used it when they were on the road as a sketchpad, and took it back to the studio when they recorded Amnesiac. Brian Eno was an early fan of the software, using it to craft 2005’s Another Day on Earth and most of his productions after that.

Hollywood composer and ex-PWEI frontman Clint Mansell was introduced to Logic by Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor while he was working on the score to Darren Aronofsky’s bizarre sci-fi thriller Pi, and he’s never looked back, using it to sketch out each one of his projects since.

They would probably deny it now, but mysterious Scottish brothers Boards of Canada did reveal in a rare interview in 2005 that while they don’t really use much software at all, they arrange their tracks in Logic.

Heard on:

Clint Mansell – ‘πr²’ (1998)

Kanye West – ‘All Falls Down’ (2004)

Brian Eno – ‘Complex Heaven’ (2010)

L1 Ultramaximizer (1994)

Waves was established in Israel in 1992 by producer Gilad Keren and musician Meir Sha’ashua, and the company became famous for releasing the world’s very first audio plug-in. The concept of plug-ins was already established – mostly thanks to photo editing software such as Adobe’s popular Photoshop – but the audio plug-in was still novel when Waves Q10 Paragraphic EQ hit the shelves. The Q10 is still popular today, but it’s not the company’s most influential or ubiquitous release – that award goes to their popular limiter the L1 Ultramaximizer.

The L1 was released in 1994, and along with its follow-up products L2 (2000) and L3 (2005), is one of the plugins that’s found in most studios, as well as one of the most controversial.

What does it do?

The Ultramaximizer isn’t exactly packed with features, but it really doesn’t need to be. It’s a limiter, so to put it simply, if you pipe a track through it that doesn’t sound quite loud enough, after some fiddling with the settings you’re quickly able to get it sounding as “huge” as tracks you hear on the radio (or on Soundcloud) without a great deal of effort. Whether that’s a good thing or not is still a cause of seemingly endless debate.

Recent revisions have allowed for more complex (and more subtle) treatment of the sound, such as EQ prioritization and better dithering, but if you’re using Ultramaximizer, you’re probably after one thing – loudness.

Who used it?

Pretty much everyone. Its results are partly responsible for the “loudness wars” – the constant creep as pop music gets progressively louder and louder – and it’s also regularly used on leaks or early drops in lieu of “proper” mastering. Most ‘credible’ artists are loth to mention their usage, as it’s considered that dirty a trick, but that doesn’t mean they’re not using it all the same.

Seeing one or more instances being used to boost up the levels before a cheeky YouTube or Soundcloud drop is very normal – EDM producer Bassnectar has copped to this, even if nobody else has – and if you download a track and the peaks are smashed into a solid block, there’s a damn good chance it’s seen an Ultramaximizer.

Producer to the stars Dr. Luke boldly revealed that he uses L2 on “pretty much everything” (that shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone who’s heard his massively distorted output) and Tom Elmhirst, who famously put his spin on Adele’s ‘Rolling in the Deep’, also hammers the plug-in – but noted in a Sound on Sound interview that he makes sure to remove the limiting before sending the finished track for mastering. That said, even mastering engineers have been found to favor the Ultramaximizer – Drew Lavyne, who has put his sparkle on records for Van Halen, White Stripes and more, is a big fan of the software and certainly doesn’t seem to be struggling.

Heard on:

Miley Cyrus – ‘Party in the USA (2009)

Katy Perry – ‘California Gurls’ (2010)

Siriusmo – ‘Feromonikon’ (2011)

Auto-Tune (1997)

It would be tough to find a pop song in 2014 that hadn’t used Auto-Tune at some stage in the production, which is amusing when you consider that it was never intended to be used on vocals at all. The software was created by Exxon engineer Andy Hildebrand accidentally, when he was attempting to develop a way to interpret complicated seismic data. At some point in the process he began to realize that the technology he’d invented could also be used to analyze and modify the pitch in audio files, and Auto-Tune was born.

Available as both a piece of hardware and a software plug-in, Auto-Tune has been available since 1997 and is probably even more controversial than Waves’ Ultramaximizer, even influencing Jay Z to call for its death on 2009’s ‘D.O.A. (Death of Auto-Tune)’.

What does it do?

Auto-Tune does exactly what it says on the tin – if you sing through a microphone hooked up to it, the program (or its hardware counterpart) will bend the pitch to the nearest semitone and center the vocal. It can be used subtly so the effect is barely audible, or the settings can be abused to create an almost vocoder-like sound. Who said influential software needed bells and whistles?

Who used it?

We can blame producers Mark Taylor and Brian Rawling for really introducing Auto-Tune to the world, when they crafted Cher’s 1998 hit ‘Believe’. While experimenting with the settings they realized that they could create a robotic vocal effect that nobody had used before, and since then the sound has rarely been far from the charts. They did attempt to throw people off the scent when they were asked about the production in 1999 by Sound on Sound, by telling the magazine that they had used a Digitech Talker pedal to manipulate Cher’s voice, but it was later confirmed to have been Auto-Tune all along.

In a 2006 interview with Pitchfork, singer Neko Case recalled talking to an engineer who revealed that it was only her and Nelly Furtado who’d never used Auto-Tune in his studio, so it would be correct to say that the software is now something of a norm. It’s not only confined to the studio either – live performers have taken to using to using Auto-Tune as a safety net while singing on stage, and it was even revealed in 2010 to have been used on competitors on the British reality singing show X-Factor to improve their performances.

Auto-Tune was picked up by Jamaican dancehall producers, and even more notably by U.S rappers who suddenly realized they didn’t need to book a session with Nate Dogg to get that all-important pop hook. T-Pain is widely credited with helping to popularize the sound in the U.S. – his album Rappa Turnt Sanga led to the robotic croon becoming something of a calling card, and after that the effect snowballed. Auto-Tune was all over Lil Wayne’s Tha Carter III and Kanye West’s game-changing 808s and Heartbreak, and it’s hard to imagine what Future, Rich Homie Quan and Young Thug would be able to achieve without it.

Heard on:

Cher – ‘Believe’ (1998)

T-Pain – ‘I’m Sprung’ (2005)

Kanye West – ‘Heartless’ (2008)

FL Studio (1997)

Influenced by innovative softsynth/drum machine combo ReBirth RB-338, young developer Didier Dambrin (known as Gol) developed a simple 16-step sequencer – basically a MIDI drum machine – which he called FruityLoops. Employed by tiny Belgian studio Image Line, Gol had no idea that the program would be so popular, and quickly attempted to develop it as the demo version brought Image Line’s servers to a standstill.

Fast forward to 1999 and FruityLoops was shaping up to be quite the workhorse. Version 1.5 introduced a built-in monosynth – the ironically-monikered TS404 – and version 1.6.5 added support for VST plugins. It was becoming clear that what that started life as a simple, hassle-free step sequencer was quickly transforming into a program you could use to make complex, high quality productions, and this was still only the beginning.

Further revisions added Fruity’s soon to be legendary piano roll, which allowed producers to draw in notes and write melodies as easily as they could trigger samples and synthesizer sounds, so when VST instrument support followed there was little else needed to make it a fully functioning DAW. The snappy name, however, started to become a big problem for Image Line. The development team began to resent having to explain that yes, they were a serious company, every time they met with hardware manufacturers, and when they were challenged by Kellogg’s while applying for a US trademark, it was the last straw. They decided to avoid a prolonged, expensive legal battle and settled on the name FL Studio.

What does it do?

Initially a simplistic drum machine, FL Studio is now one of the world’s leading DAWs, offering the kind of sequencing and editing you’d expect to find in Logic Pro or Cubase, yet still containing the incredibly intuitive 16-step drum programming and much-loved piano roll features that has made it so appealing to artists wanting to knock together ideas in a hurry. It’s also jam packed full of effects, leading some artists (Aussie drum’n’bassers Pendulum, for example) to use it simply for the suite of plugins and leave the sequencing to another program altogether.

Who used it?

You can’t mention FL Studio without acknowledging its massive influence on rap music, and since being revealed as the tool behind Soulja Boy’s ’07 hit ‘Crank That’ it’s been a regular feature in most young rap producers’ arsenals. Lex Luger famously used the software to rustle together Rick Ross’s gigantic hit ‘B.M.F.’, Drake affiliate Boi-1da uses it, and Chief Keef’s hitmaker Young Chop helped solidify Chicago’s drill sound with it. Basically if you’re listening to rap in 2014, you’ve heard FL Studio, and if you’re making rap in 2014, you’re probably already using it.

It’s not only rap producers that have taken to the software though: Skream graduated from Music 2000 and used FL Studio to produce breakout dubstep anthem ‘Midnight Request Line’, and it’s also a favorite tool of EDM superstars Avicii, Afrojack and Deadmau5. Deadmau5 in fact has revealed that the groundwork for all of his tracks is done in FL Studio before he exports the beats and melodies to use elsewhere.

Heard on:

D4L – ‘Laffy Taffy’ (2005)

Soulja Boy – ‘Crank That’ (2007)

Rick Ross – ‘B.M.F.’ (2010)

MUSIC (1998)

Launched in 1998 and endorsed by the then massive Judge Jules, MUSIC brought music sequencing to the Sony Playstation, and to kids who maybe didn’t have (or didn’t want) access to a fancy PC and soundcard. It was a basic program with only limited functionality, but its follow-up Music 2000 (known in the US as MTV Music Generator) was about as close to a music sequencer as you could get without shelling out real money.

Amazingly, this new version added MIDI support and even basic sampling – users could replace the game’s PS1 CD with an audio CD and rip, chop and edit samples to their heart’s content, or even record their own sounds from scratch by connecting up a microphone. It might not have been considered anywhere near professional at the time, but you got a great deal for your money.

What did it do?

MUSIC and its follow-up came with a whole suite of samples and sounds which could be fitted together like building blocks, giving a hint of fun and accessibility to the steep learning curve usually associated with DAW software (thanks for that one Logic!). Music 2000 also sported a quite reasonable 24 audio tracks and MIDI compatibility, which mean that if you happened to have a cheap MIDI keyboard in the house for some reason, you could hook it up and jam out to your heart’s content. It still sounded a little off when compared with the PC/Mac options at the time – Cubase or Logic for example – but that only added to its charm.

Who used it?

Emerging at the tail end of the 1990s, MUSIC appeared at just the right time for a generation of bored school kids to kickstart a music career without even noticing it. It’s simplicity and speed made it popular amongst young grime producers and put it at the center of a scene far less concerned with high fidelity than it was with simple 8-bar loops that could be blasted from a cellphone and discarded.

Brothers Skepta and JME graduated to Music 2000 from Mario Paint and breakout grime outfit So Solid Crew managed to eke a couple of bona fide hits from the software, so it wasn’t long before word started to spread that it was more than merely a toy.

Elsewhere in London, Benga and Skream both used to bang out tracks with it regularly – Benga even gave a quick demonstration to Red Bull Music Academy and made a track while he was being interviewed. Glaswegian producer Hudson Mohawke also told FACT that it was where he first learned to cut up samples and loops.

It wasn’t just the UK that cracked on to Music’s appeal either. Lex Luger discovered his talent for beats while fiddling with MTV Music Generator 3, and videogame composer Jim Guthrie still finds time to put in the hours on the software. Apparently he still keeps a PS1 around just to use MTV Music Generator, and even takes it on the tour bus with him.

Heard on:

So Solid Crew – ‘Dilemma’ (2000)

So Solid Crew – ‘Oh No’ (2000)

Skepta – ‘Gun Shot Riddim (Pulse Eskimo)’ (2002)

Reaktor (1999)

Native Instruments’ Reaktor was a rare software synthesis package that offered functionality a hardware alternative would struggle with. It wasn’t a million miles away from Cycling ‘74’s Max/MSP, in that it worked as a patchable set of tools that could be strung together to create elaborate synthesizers, effects, samplers and sequencers, but its appearance and massive set of libraries (pre-programmed instruments and effects) made it far more attractive to the novice user.

It started life as Generator, a fairly limited modular synthesizer, but was given a shot of adrenaline with the addition of sample manipulation package Transformator. The two programs together became Reaktor and offered a wealth of options to producers bored with the tinny sounds of Retro AS-1, Steinberg Neon or a CPU-hogging Moog approximation.

Since its initial release, Reaktor has been expanded to include more libraries, more modules and a simpler interface, but while we’re now on version 5.5, the basic concept is still very much the same.

What does it do?

Like Max, a user can tailor Reaktor to make whatever kind of sound or structure they might need. While most users will gravitate towards its excellent selection of preset synthesizers and sample tools, a quick fiddle under the hood and you can design searing digital noise generators or a fully functional, custom-built live setup. It’s still a softsynth of sorts, certainly, but it’s one that can sound exactly how you want it to providing you’re willing to spend the time figuring out its complexities.

Who uses it?

Typically, because of Reaktor’s proposed world of possibilities it was picked up by curious electronic musicians desperate to emulate Richard D. James’ and Autechre’s complicated setups without shelling out for a studio’s worth of expensive gear. Tim Hecker was one such young’un who placed Reaktor at the center of his sound, but instead of mimicking his peers, he used the software to create lush, sample-based granular pads that people still associate with him to this day.

It didn’t go unnoticed by the IDM elite, either – Squarepusher picked up Reaktor in 2001 and has used it extensively ever since to build tools that would be immensely difficult to engineer outside of the box. Similarly, Schematic’s Richard Devine has been spotted building custom patches for Reaktor, coming up with the bizarre and brilliant electroacoustic ensemble Graincube.

More recently Warp’s Tim Exile revealed that his live setup is based entirely around a custom Reaktor patch that he’s been developing for many years. The program allowed him to slowly build the setup as his sound morphed and grew, and gives him total control over his bizarre and innovative setup.

Heard on:

Mouse on Mars – ‘Doit’ (2001)

Tim Hecker – ‘Balkanize-You’ (2004)

Squarepusher – ‘Abstract Lover’ (2010)

Reason (2000)

In 1997, tiny Swedish studio Propellerhead Software released a program called ReBirth RB-338, a step sequencer that featured clones of Roland’s best-loved dance music synths – the TB-303, the TR-808 and the TR-909. What it lacked in complicated sequencing functions it made up for in sheer usability, and the program was a massive success (just listen to Youngstar’s classic ‘Pulse X’ to hear it in action), but it was never exactly what the developers had in mind.

Reason, which emerged three years later, was the program Propellerhead had always wanted to make, and they’ve even said that prototypes exist of the software long before ReBirth ever reared its head. There were similarities – the step sequencing, for starters – but it was the software’s innovative “gear-like” patching that made it so intuitive, especially for novice users who weren’t familiar with the then-established language of the DAWs.

In the beginning Reason didn’t even have an audio input, but it didn’t need to – its range of samplers, sequencers and software synthesizers were enough for users to compose high quality tracks without ever leaving the program, and if people did need more, then they could run it alongside Cubase or Logic using ReWire, Propellerhead’s tool that allowed other DAWs to treat Reason like a plugin.

Propellerhead eventually developed their own audio recording software, named simply Record, to fill the gap, but after it failed to capture the imagination of, well, anyone, it was integrated into Reason in 2011.

What does it do?

Initially, Reason was more a tight selection of softsynths than a DAW, but its high quality sound and insanely easy-to-use routing made it far more versatile than you might initially expect. The mixer function is about as close as you’ll get to owning a real mixer without actually heading down to Guitar Center and picking one up, and the suite of synthesizers and drum machines sounded way better (and more importantly were quicker and easier to use) than most alternatives on the market at that time.

With the addition of an audio recording engine there’s now little in terms of functionality to separate Reason from any other of its competing DAWs, and it just comes down to the wide selection of softsynths, massive banks of samples and the generous suite of effects to give Reason the competitive edge.

Who used it?

Like Music 2000, Reason was many young musicians’ first taste of music production, and as Propellerhead allowed it to grow so quickly, there wasn’t really ever a reason to abandon it. Brummie grime producer Preditah was using it from day one, and it’s probably no accident that his moniker closely resembles that of a Reason softsynth. LA beat scene nucleus Flying Lotus has used Reason for a number of years and still champions the software now, though he pairs it up with Ableton Live.

The software also became popular among young rap producers, the most prominent of which has to be LA ratchet pioneer DJ Mustard, who claims it’s the “only thing” he uses to make beats.

Even wise old hands have nosed in on the action – Luke Vibert, The Prodigy’s Liam Howlett and A Guy Called Gerald have confirmed their use of the software, despite all having a history with some of the 20th century’s most prized analogue gear, and synthesizer gods Kraftwerk have also been spotted tinkering.

Heard on:

T.I. – ‘What You Know’ (2006)

Kanye West – ‘Big Brother’ (2007)

Young Jeezy – ‘R.I.P.’ (2012)

Ableton Live (2001)

Live appeared in 2001 at a time when electronic music – specifically live electronic music – had begun to stagnate. Live performance was now an expected norm, but was a massive chore simply because the available options weren’t always that beneficial for a musician who primarily worked in the studio. You could purchase Max/MSP and try and use one of the popular looping patches that were floating around mIRC, you could stream from your favorite DAW (which was seen as a cop out even then), or you could attempt to make the move to outboard gear, and most of those options were fraught with their own particular problems.

Seeing a massive gap in the market, Bernd Roggendorf and Gerhard Behles (who was then a still a member of Monolake) formed Ableton and began to develop a brand new DAW from the ground up, avoiding some of the maddening elements of Logic, Cubase and Pro Tools, and making sure that live performance was at the very center of its functionality. Monolake’s Robert Henke also lent a hand, trialing the early versions and making sure that the program made sense to a musician, as well as offering the kind of tools he needed on a day-to-day basis. The result was Live, a program built to function as an intuitive loop-based sequencer as well as a fully-functional DAW.

Since its release, Live hasn’t been overhauled so much as it has been fine-tuned. More effects have been jammed into the now-extensive library, it’s been given its own suite of virtual instruments, and most interestingly it has absorbed Cycling ‘74’s Max (since 2010 you have been able to run Max inside of Live), but essentially it’s the same program as it always was, and is all the better for it.

What does it do?

The way Live allows electronic acts to perform their compositions in the live environment is its biggest initial draw. When you open the software you’re treated to a screen of grey boxes, and each one can be filled with a sample, sequence or long recording and triggered on request by the performer. It’s solid and functional yet alarmingly simple, and the ability to route sound out and back into the rig allows Live to play well with whatever outboard effects you might fancy inserting into the mix.

Unlike other DAWs, Live is also a potent DJ tool, even though it was probably never initially intended to be used in that manner. The program’s excellent audio manipulation tools mean that synching a selection of tracks to a specific tempo is incredibly simple, and it makes laptop DJing without using an external setup like Serato surprisingly fluid.

It’s also worth noting Live’s exceptional library of effects, samplers and softsynths, and since the development team came from an electronic music background, each plug-in feels as if it’s been created with a specific use in mind that actually relates to the way an electronic musician works, whether in a bedroom studio or on a more professional level.

Who uses it?

For a while it was unusual to see an electronic musician performing who wasn’t using Live, and since its release it’s become just as common to see the program used as a studio tool. Monolake’s Robert Henke might be an obvious user, but his last couple of albums serve as prime examples of the quality Live is capable of. His associate Torsten Pröfrock (aka T++) can also be considered a power user.

EDM superstars Deadmau5 and David Guetta also aren’t shy about their Live usage, and it’s become a favorite of Flying Lotus (who uses it in conjunction with Reason), Hot Chip, Telefon Tel Aviv, Nosaj Thing and Jan Jelinek.

Heard on:

Christian Kleine – ‘Stations’ (2004)

T++ – ‘Space Pong’ (2006)

Monolake – ‘Infinite Snow’ (2009)

Garageband (2004)

Seeing the rise of easy-to-use music creation software such as FruityLoops and Reason in the early ‘00s, Apple knew they needed something that could interest new users with a user-friendly system. When they acquired Emagic in 2002 it was the perfect opportunity, and lead developer Gerhard Lengeling set to work creating a stripped down, easy-to-use DAW that was based on Logic Pro’s tried and tested core engine.

The software was labeled Garageband and debuted in early 2004. It featured basic MIDI sequencing, audio recording, virtual instruments and support for plug-ins, but was bundled with every new Macintosh computer sold as part of their extensive iLife collection. This meant that individuals purchasing a sparkly new iMac were suddenly saddled with music creation software whether they liked it or not, and that’s exactly what Apple wanted.

Like iMovie and iPhoto before it, Garageband was an incredibly high-functioning piece of software, and while it lacks many of the pro features of big daddy Logic, it would be silly to pass it off as a useless toy. As the software progressed it got closer and closer to Logic, and now offers 24-bit recording, notation, automation and even complex time stretching – something that only a few years ago would have been priced at a premium.

In 2011, Apple released an app version of Garageband that could be used with the iPad and later iPhone and iPod Touch, ushering in a wave of compact DAWs that could be used while standing in the corner of the club listening to minimal techno.

What does it do?

Garageband’s main draw is its usability, and while it’s pretty feature-packed for what’s basically a piece of free software, none of the additional options makes it too intimidating for beginners. Budding producers can easily record vocals or instruments directly into the arrange panel and even pitch-match and lock the sounds to a tempo, before adding beats, samples and synthesizers from an array of included plug-ins.

Who used it?

While it’s not exactly been championed as a replacement for Pro Tools in the professional studio, Garageband has become something of a sketchpad for musicians. While Michael Jackson was stuck having to sing his various parts into a dictaphone before bringing the ideas to Quincy Jones in the studio, today’s artists – Kate Nash, Fred Durst and Courtney Love included – can now demo fully sequenced tracks on Garageband.

T-Pain claims it was necessity that drew him to Garageband – the power went out in his studio and the only thing that he could use was a laptop. While he’d never tried Garageband before, he booted it up and says in 40 minutes he had a good beat, then 40 minutes later he’d finished ‘I’m ‘n Luv (Wit a Stripper)’.

Sometimes it’s only the library of samples that have appeared in songs – Terius Nash and Christopher ‘Tricky’ Stewart used ‘Vintage Funk Kit 03’ as the beat on Rihanna’s ‘Umbrella’ and Polow Da Don used a whole heap of Garageband loops to construct Usher’s ‘Love in This Club’.

Heard on:

T-Pain – ‘I’m ‘n Luv (Wit a Stripper)’ (2005)

Rihanna – ‘Umbrella’ (2007)

Usher – ‘Love in this Club’ (2008)

Read next: The 14 most important synths in electronic music history – and the musicians who use them